Healing the Nation: Navigating the Complexities of the Indian Health Service and the Promise of Indigenous Wellness

In the vast, diverse landscape of Native America, healthcare is a tapestry woven with threads of profound historical context, persistent challenges, and remarkable resilience. At its center lies the Indian Health Service (IHS), a federal agency tasked with providing healthcare to over 2.6 million American Indians and Alaska Natives across 37 states. Born from treaty obligations and a history of systemic neglect, the IHS stands as a critical, yet often beleaguered, pillar of health for Indigenous communities. But beyond the clinic walls, a powerful resurgence of Indigenous wellness approaches is charting a new course, demonstrating that true healing extends far beyond Western biomedical models, embracing the holistic well-being of mind, body, spirit, community, and land.

The IHS’s mandate is rooted in a series of treaties and agreements between sovereign tribal nations and the U.S. government, often referred to as a "sacred trust." These agreements exchanged vast tracts of land for promises of basic services, including healthcare. Established in 1955, though its roots stretch back to the 1830s with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the IHS operates a network of hospitals, clinics, and health stations, supplemented by services provided through tribally-operated facilities under self-governance contracts and compacts (known as "638 contracts"). This system is unique, representing a direct federal responsibility to a specific population.

However, the reality of IHS healthcare often falls short of its foundational promise. For decades, the agency has been chronically underfunded, operating at a fraction of what is needed to provide equitable care. According to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), federal spending on healthcare for American Indians and Alaska Natives is often cited as less than half of federal spending per capita for other Americans. This disparity translates into a dire lack of resources: dilapidated facilities, outdated equipment, severe staffing shortages, and long wait times for appointments, especially for specialty care. In many remote tribal communities, patients face hundreds of miles of travel for basic services, compounding the challenges of access.

These systemic deficiencies directly contribute to alarming health disparities. American Indians and Alaska Natives experience significantly higher rates of chronic diseases compared to the general U.S. population. Diabetes rates are 2.2 times higher, while heart disease and stroke mortality are substantially elevated. Mental health crises are pervasive, with suicide rates among youth and young adults being 1.5 times the national average. Substance abuse disorders, particularly opioid addiction, disproportionately affect Indigenous communities, often exacerbated by the intergenerational trauma stemming from historical injustices like forced relocation, cultural assimilation, and the residential school system. As one tribal elder succinctly put it, "Our bodies remember what our people endured."

The impact of historical trauma cannot be overstated. It is a collective, cumulative wound that manifests not only in mental health challenges but also in chronic physical ailments. The erosion of cultural practices, language, and traditional ways of life severed vital connections that once fostered community health and resilience. For too long, Western medicine, as delivered through the IHS, has often failed to acknowledge or adequately address these deep-seated, culturally specific determinants of health, focusing instead on treating symptoms rather than the root causes.

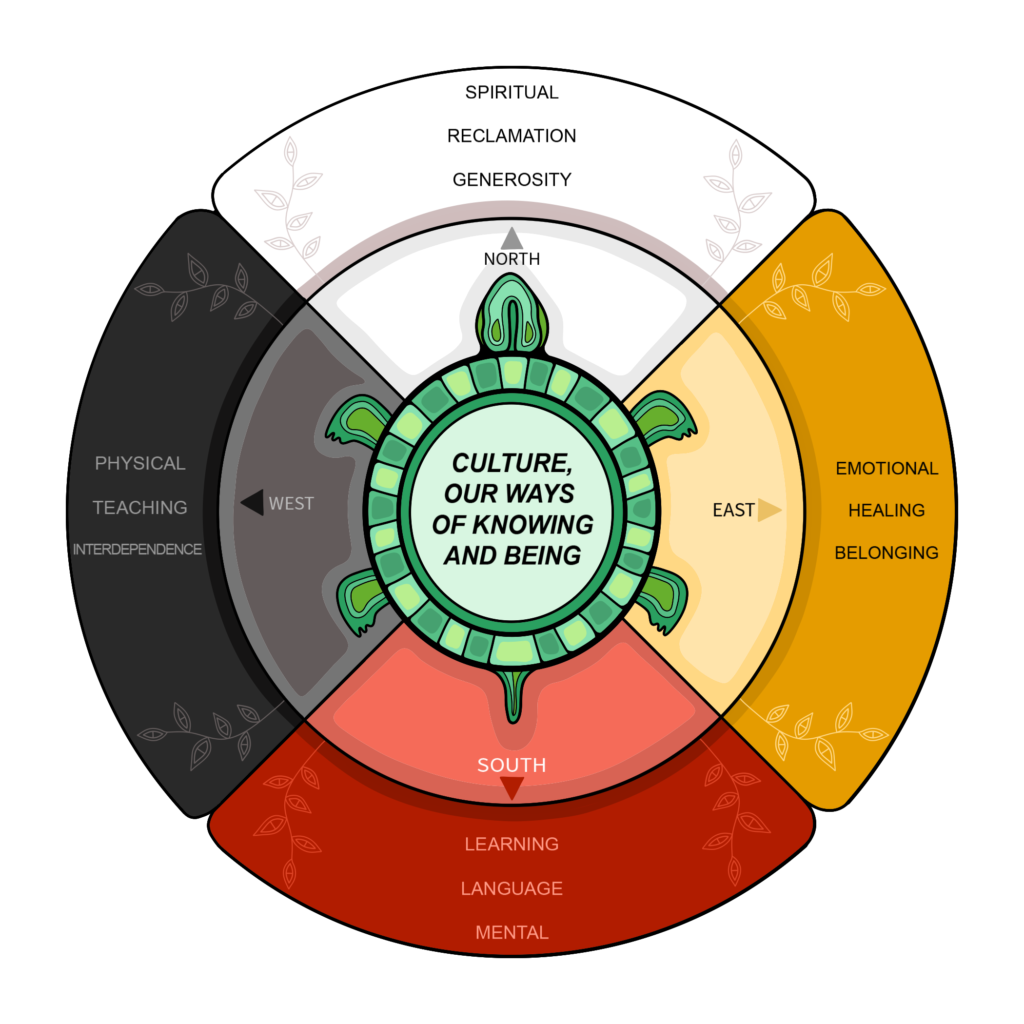

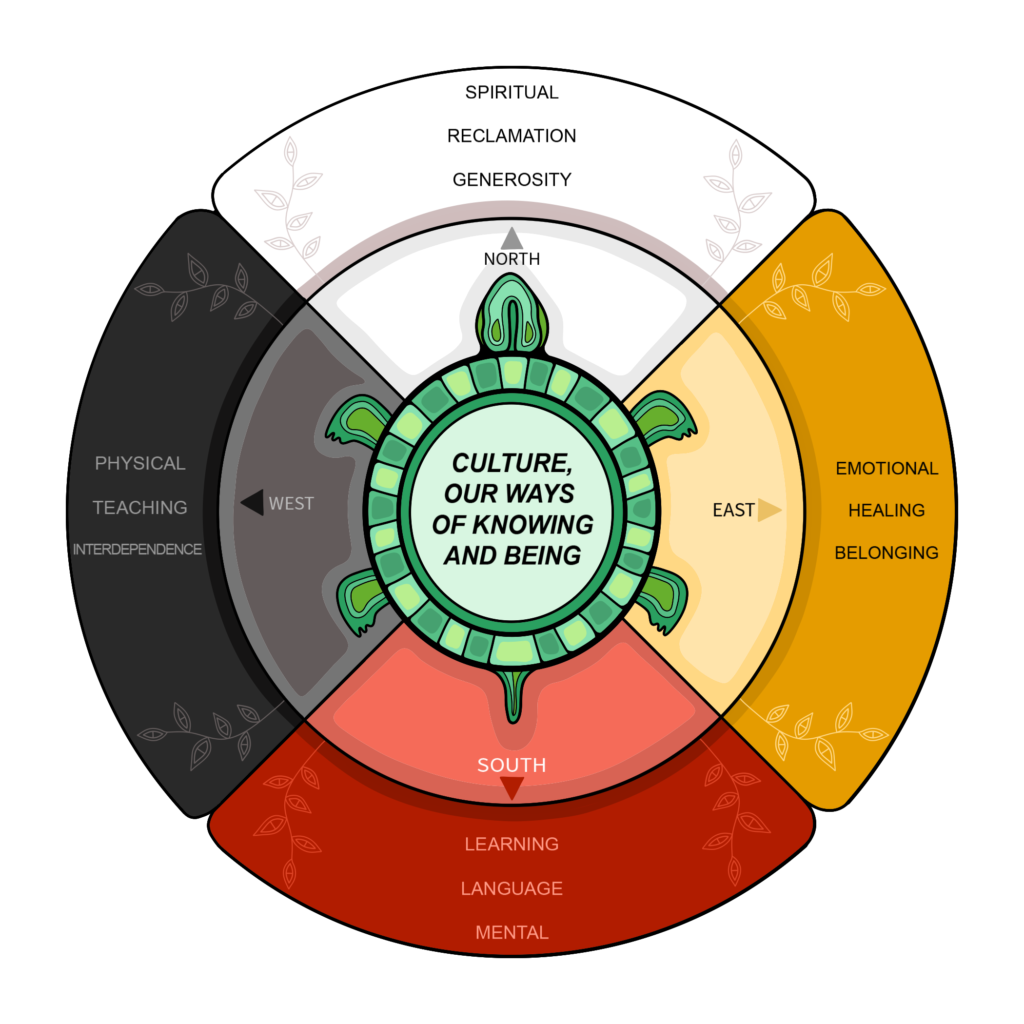

Yet, amidst these profound challenges, a powerful movement is gaining momentum: the revitalization and reassertion of Indigenous wellness approaches. This paradigm shift recognizes that health is not merely the absence of disease, but a holistic state encompassing physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and communal well-being, deeply intertwined with the land and cultural identity. It is a return to traditional teachings that predate colonial contact, emphasizing balance, harmony, and connection.

Indigenous wellness is inherently holistic. It understands that an individual cannot be truly healthy if their community is struggling, if their spiritual needs are unmet, or if their connection to their ancestral lands is severed. Traditional healing practices, often dismissed by Western medicine, are central to this approach. These can include:

- Ceremony and Rituals: Sweat lodges, pipe ceremonies, sun dances, and other sacred practices provide spiritual cleansing, emotional release, and a reaffirmation of cultural identity and communal bonds.

- Traditional Medicine: The use of plant-based remedies, often passed down through generations, along with practices like smudging (burning sacred herbs) for purification.

- Talking Circles and Storytelling: These communal practices foster open communication, emotional support, and the sharing of experiences, particularly vital for mental health and processing trauma.

- Connection to Land and Nature: Spending time in nature, engaging in traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering, and caring for the environment are seen as fundamental to well-being, embodying the belief that "when the land is sick, we are sick."

- Language Revitalization: Reclaiming ancestral languages is a powerful act of cultural affirmation, fostering identity, self-esteem, and a deeper understanding of traditional knowledge embedded within the language itself.

- Food Sovereignty: Initiatives aimed at re-establishing traditional food systems – growing native crops, hunting, and foraging – combat diet-related diseases like diabetes and reconnect communities with ancestral knowledge and healthy eating habits.

Tribal nations, through their inherent sovereignty and self-determination, are increasingly leading the charge in integrating these wellness approaches into their healthcare systems. Many tribes have taken over the management of their IHS facilities through "638 contracts," allowing them greater control over budgets and program design, and enabling them to tailor services to their specific cultural needs. This shift is crucial for fostering trust and ensuring culturally competent care.

For example, many tribal health centers now employ both Western-trained medical professionals and traditional healers, recognizing the value of both perspectives. Mental health programs are incorporating talking circles, equine therapy, and culturally specific counseling that addresses historical trauma. Diabetes prevention programs emphasize traditional foods and active lifestyles rooted in ancestral practices. Youth programs focus on cultural immersion, mentorship, and rites of passage to build resilience and identity, effectively acting as preventative mental health measures.

As Dr. Mary Owen (Tlingit), president of the Association of American Indian Physicians, noted, "For too long, the system has tried to fix Native people. What we need is a system that supports Native people in healing themselves, in ways that are culturally appropriate and strengthen their identity." This sentiment underscores the need for a fundamental shift in how healthcare is conceived and delivered to Indigenous populations.

The integration of Indigenous wellness approaches into the broader healthcare landscape is not without its challenges. Bureaucratic hurdles, funding limitations that often do not recognize traditional healing practices, and a lingering bias within some Western medical establishments against non-pharmacological interventions can impede progress. Furthermore, the sheer diversity of tribal cultures means there is no one-size-fits-all "Indigenous wellness" model; approaches must be tailored to the specific traditions and needs of each community.

However, the potential for profound positive impact is immense. By embracing and adequately funding Indigenous-led wellness initiatives, the IHS and the U.S. government can begin to truly honor their treaty obligations and address the deep-seated health inequities. This means not just increasing appropriations for IHS, but also investing in tribal health departments, supporting traditional healers, funding language and cultural programs, and empowering communities to design and implement their own health solutions.

The path forward demands genuine partnership, respect for tribal sovereignty, and a fundamental shift in perspective from one of paternalistic provision to one of collaborative empowerment. As Indigenous communities continue to reclaim their knowledge, languages, and healing traditions, they offer not only a beacon of hope for their own people but also invaluable lessons for the broader world about holistic health, community resilience, and the enduring power of cultural identity in the journey toward true well-being. The healing of the nation, in its fullest sense, requires acknowledging the wounds of the past and embracing the wisdom of Indigenous futures.