The Ghost of Giants: How Megafauna Extinction Forged Early Humanity

Imagine a world teeming with colossal beasts: woolly mammoths thundering across frozen steppes, saber-toothed cats stalking through primeval forests, giant ground sloths browsing on lush vegetation. For hundreds of thousands of years, these megafauna – animals weighing over 44 kg (100 lbs) – were not just part of the landscape; they were the very bedrock of the ecosystem, and for early humans, a critical resource that shaped their lives, their cultures, and ultimately, their destiny. Then, over a relatively short geological blink, they vanished.

The Late Pleistocene, roughly 50,000 to 10,000 years ago, witnessed one of the most dramatic extinction events in Earth’s history. Across every continent except Antarctica, giant mammals disappeared with chilling regularity. In North America, some 70% of large mammal genera vanished, including mammoths, mastodons, dire wolves, and giant short-faced bears. South America lost nearly 90% of its megafauna, while Australia saw the demise of its own unique giants like the Diprotodon (a massive marsupial) and the Genyornis (a giant flightless bird). Europe and Asia, though experiencing less dramatic losses, still bid farewell to woolly rhinos and cave bears.

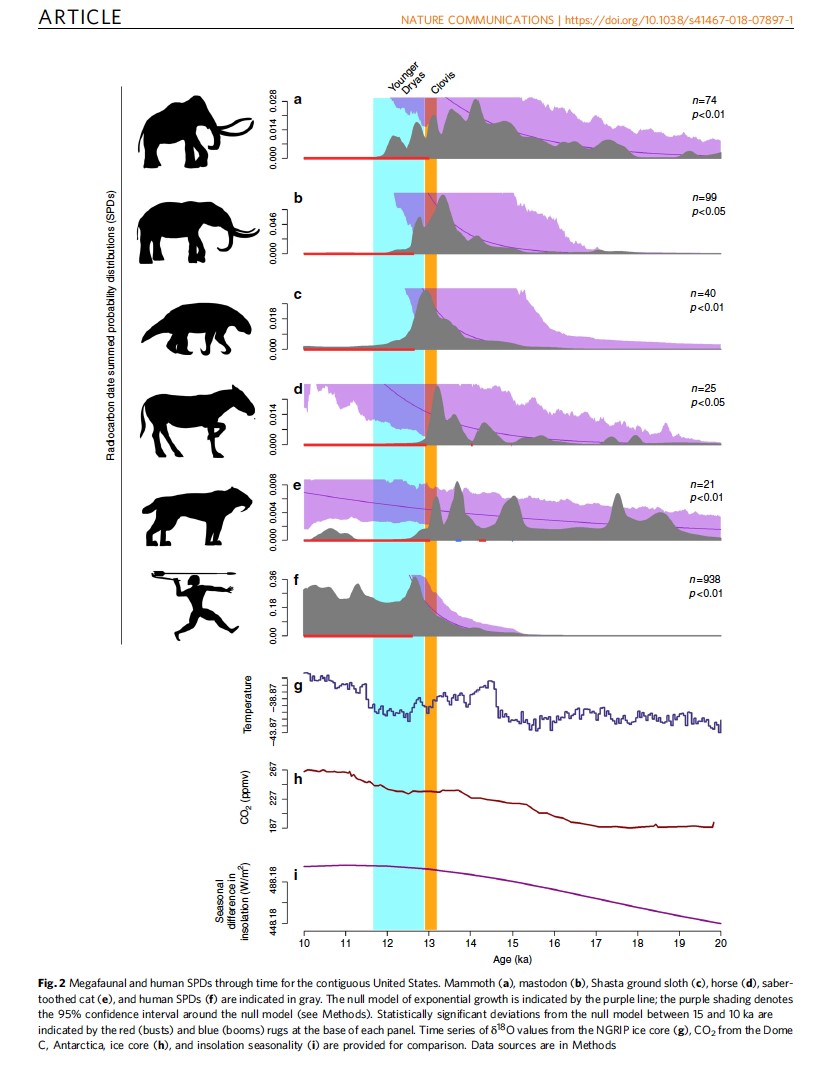

This mass extinction event, often termed the "Quaternary Extinction Event," coincided uncannily with the global expansion of Homo sapiens. The question of what caused this widespread die-off remains one of archaeology and palaeontology’s most enduring debates: was it rapid climate change, the relentless hunting pressure from a newly dominant predator – early humans – or a complex interplay of both?

The Great Debate: Climate vs. Overkill

The "Overkill Hypothesis," famously championed by palaeontologist Paul S. Martin in the 1960s, posits that as anatomically modern humans migrated out of Africa and across the globe, they encountered megafauna naive to human predation. These large, slow-reproducing animals, unaccustomed to the sophisticated hunting techniques and collaborative strategies of Homo sapiens, were systematically hunted to extinction. Martin famously described humans as "blitzkrieg hunters," sweeping across continents and leaving a trail of vanished giants in their wake. The timing often aligns: humans arrive, megafauna disappear shortly after.

Conversely, the "Climate Change Hypothesis" attributes the extinctions primarily to the dramatic and rapid fluctuations of the Late Pleistocene ice ages. As glaciers advanced and retreated, landscapes transformed, vegetation patterns shifted, and habitats fragmented. Such changes, proponents argue, would have stressed megafauna populations, making them vulnerable to disease, starvation, and reproductive failure. The Younger Dryas, a sudden return to near-glacial conditions around 12,900 to 11,700 years ago, is often cited as a particularly devastating climatic event.

Today, the scientific consensus largely leans towards a synergistic model, acknowledging that it was likely a "double whammy." Climate change certainly put stress on populations, altering their environment and food sources. However, the arrival of humans, armed with increasingly effective hunting technologies and a capacity for rapid population growth, delivered the "killing blow." As Dr. Anthony Barnosky, a prominent palaeontologist, once observed, "It’s like a patient with a chronic disease being hit by a bus. The disease might not have killed them, but the bus certainly did." Humans were the bus.

The Immediate Impact: A World Without Giants

For early humans, the disappearance of megafauna was not just an ecological shift; it was a profound transformation of their very existence. The immediate impact was most keenly felt in the realm of sustenance and resources.

Megafauna, particularly herbivores like mammoths and bison, represented an enormous, concentrated source of protein, fat, and calories. A single mammoth could feed a band of hunters for weeks, providing not just meat but also a wealth of other essential materials. "Imagine the sheer abundance," says archaeologist Dr. Emma Jenkins. "A successful mammoth hunt meant not just a feast, but a winter’s worth of supplies. Its loss would have created an immediate and existential crisis for societies built around hunting these giants."

Beyond food, megafauna provided a critical raw material base. Their bones were fashioned into tools, weapons, and even structural elements for shelters, such as the elaborate mammoth bone huts found in Ukraine. Their massive hides offered warmth, protection, and materials for clothing, tents, and ropes. Tendons provided strong sinews, and tusks yielded ivory for art and specialized tools. The loss of these giants meant the loss of a multi-purpose resource that had underpinned human technology and survival strategies for millennia.

Furthermore, megafauna held deep cultural and spiritual significance. Cave paintings in Europe, like those at Lascaux and Altamira, vividly depict mammoths, woolly rhinos, and giant deer, testifying to their central role in the human psyche, likely as totemic figures, symbols of power, or objects of reverence. Their disappearance would have left a void not just in the physical landscape, but in the spiritual and mythological landscape of early human societies.

Adaptive Responses: Innovation in the Face of Loss

Yet, humans are nothing if not adaptable. The extinction of megafauna, while devastating, also served as a powerful catalyst for innovation, forcing early humans to fundamentally rethink their subsistence strategies and technologies.

One of the most significant shifts was the move towards what archaeologists call the "broad-spectrum revolution." As large game became scarce, humans diversified their diets, increasingly exploiting a wider array of smaller animals – deer, fish, birds, rabbits – and a broader range of plant resources. This required new hunting techniques and tools: instead of large spears designed for mammoths, humans developed bows and arrows, traps, nets, and fishing gear. This technological shift reflects an intimate understanding of diverse ecosystems and a more granular approach to resource extraction.

The pursuit of smaller, faster prey, and the more intensive gathering of plants, likely fostered greater cooperation and a more complex division of labor within human groups. It may have also encouraged a deeper knowledge of local environments, seasonal availability of resources, and sophisticated foraging schedules.

Moreover, the pressure to find new food sources and exploit different ecological niches may have accelerated human migration and dispersal into previously uninhabited or sparsely populated regions. As prime hunting grounds became barren of their giant inhabitants, groups would have been compelled to explore new territories, further solidifying humanity’s global footprint.

The Ultimate Legacy: Paving the Way for Agriculture

Perhaps the most profound and enduring legacy of megafauna extinction lies in its potential role in catalyzing the Agricultural Revolution. For tens of thousands of years, humans had been highly mobile hunter-gatherers, following game and seasonal plant cycles. The dwindling availability of large, reliable game could have provided a crucial impetus for humans to seek more stable and predictable food sources.

"The megafauna extinction created a vacuum," argues archaeologist Dr. Sarah Milligan. "It forced humans to confront the limits of hunting wild populations and to consider alternative ways to feed themselves. Domestication of plants and animals, previously perhaps just one option among many, suddenly became a vital necessity for survival."

This perspective suggests that the loss of megafauna, rather than solely being a catastrophe, was a crucible of change that pushed humanity towards sedentism, the cultivation of crops, and the domestication of animals. Without the easy bounty of the giants, humans turned their ingenuity to manipulating their environment, eventually leading to the development of agriculture in multiple independent centers around the globe. This shift from a nomadic hunting lifestyle to settled farming communities fundamentally altered human social structures, population densities, technological development, and our relationship with the natural world.

The echoes of the vanished giants still reverberate in our world. Their extinction, whether primarily human-driven or a tragic confluence of factors, represents a pivotal moment in the trajectory of our species. It challenged early humans to their core, forcing them to adapt, innovate, and ultimately, to redefine their place within the global ecosystem. From the shadow of their disappearance, a new chapter for humanity began, one that would lead us from spear-wielding hunters of titans to the architects of civilization, forever shaped by the ghost of the giants they once pursued.