Uprooted Souls, Fractured Spirits: The Enduring Impact of Forced Relocation on Tribal Identity

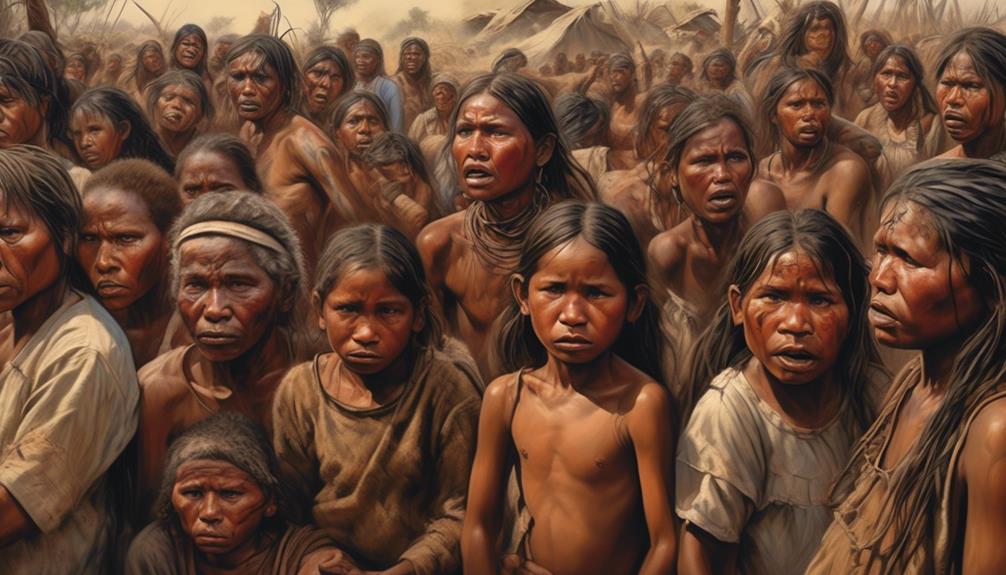

The earth beneath our feet is more than mere soil; for tribal peoples, it is the cradle of identity, the repository of memory, and the wellspring of spirituality. When this fundamental connection is severed through forced relocation, the impact resonates far beyond the physical act of displacement, tearing at the very fabric of tribal identity and leaving wounds that span generations. From the Trail of Tears to contemporary land grabs in the Amazon, the narrative of forced removal is a chilling testament to the devastating power wielded against those whose existence is intricately woven with their ancestral lands.

Tribal identity is a complex, multifaceted construct, deeply rooted in a people’s relationship with their specific geographic territory. It encompasses language, spiritual beliefs, traditional ecological knowledge, social structures, governance systems, ceremonial practices, and a profound sense of belonging. As the late Oglala Lakota scholar Vine Deloria Jr. famously stated, "The land is the sacred mother, the place from which we come and to which we return." This connection is not merely sentimental; it is existential. Land provides sustenance, medicinal plants, sacred sites for ceremony, and the physical location where ancestors are buried, linking past, present, and future generations. To be separated from this land is to lose a part of one’s soul, to be cut adrift from the very source of one’s being.

The mechanisms of forced relocation are varied but uniformly brutal. Historically, it was often an instrument of colonial expansion, driven by the desire for land, resources, or strategic advantage. Indigenous populations were deemed obstacles to "progress" or "civilization," their rights disregarded, and their claims dismissed. In the United States, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the infamous Trail of Tears, forcing the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations from their ancestral lands in the southeastern U.S. to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This brutal march, often conducted at gunpoint, resulted in the deaths of thousands from disease, starvation, and exposure. The spiritual and cultural trauma inflicted during this period is still palpable within these communities today.

"We were told that we were savages, that our way of life was inferior, that our land was needed for others," recounts a descendant of a Cherokee survivor, her voice heavy with the weight of history. "But our land was our church, our school, our pharmacy, our entire world. When they took that, they took pieces of who we were."

Beyond direct military expulsion, forced relocation can also manifest through policies that dispossess tribes of their land. The creation of reservations, often on marginal lands far from traditional territories, was another form of displacement designed to control and assimilate indigenous peoples. In Australia, Aboriginal peoples were systematically dispossessed of their lands, leading to the "Stolen Generations," where children were forcibly removed from their families and communities, a policy that fractured identity at its most fundamental level – the family unit and cultural transmission. The High Court’s Mabo decision in 1992, recognizing native title, was a landmark, but it came decades after immense damage had been done.

The immediate and most visible impact of forced relocation is the disruption of traditional economic systems. Tribes that once lived self-sufficiently through hunting, fishing, farming, and foraging suddenly found themselves without access to their traditional resources. This often led to poverty, dependence on government rations, and the erosion of age-old skills and knowledge. The shift from a subsistence economy to a cash economy, without adequate preparation or resources, can lead to chronic unemployment, poor health outcomes, and a cycle of destitution that is incredibly difficult to break.

However, the deeper, more insidious impacts are on the intangible aspects of identity. Language, for example, is the vessel of culture, carrying oral histories, traditional stories, spiritual concepts, and unique worldviews. When a community is removed from its land, the places that gave meaning to their language – the names of mountains, rivers, plants, and animals – become distant memories. Children, growing up in a new environment, often lose fluency in their ancestral tongues, leading to a profound cultural disconnect. UNESCO estimates that a language dies every two weeks, with indigenous languages being particularly vulnerable, often due to the very disruptions caused by relocation.

Spirituality also suffers immeasurably. Many tribal religions are place-based, with sacred sites, ceremonial grounds, and natural features holding immense spiritual significance. Forced removal means the loss of access to these vital spiritual anchors. Ceremonies cannot be performed correctly, traditional prayers lose their context, and the connection to the ancestors, who are often believed to reside in the land, is fractured. This can lead to a sense of spiritual emptiness, despair, and a loss of purpose within the community.

The psychological toll is perhaps the most enduring and devastating. Forced relocation engenders profound grief, trauma, and a sense of profound loss. This is not merely individual grief but collective, historical trauma that can be passed down through generations, manifesting as higher rates of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide. Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart’s work on "historical trauma" among Native Americans highlights how the cumulative emotional and psychological wounds of centuries of colonial violence, including forced removal, continue to impact indigenous communities today. Children and grandchildren carry the echoes of their ancestors’ suffering, even if they did not experience the removal firsthand.

In contemporary times, forced relocation continues, driven by resource extraction (mining, logging, oil and gas pipelines), large-scale infrastructure projects (dams, roads), and even the effects of climate change, which disproportionately impact indigenous communities. In the Amazon basin, indigenous tribes face relentless pressure from illegal logging, mining, and agricultural expansion, often leading to violent displacement and the destruction of their pristine homelands. The Yanomami, Munduruku, and Kayapó peoples, among others, continue to fight for their survival against powerful external forces. These modern displacements echo the historical patterns, proving that the threat to tribal identity remains ever-present.

Yet, despite the overwhelming forces arrayed against them, tribal communities worldwide have demonstrated remarkable resilience. In the face of displacement, many have actively worked to revitalize their languages, reclaim their spiritual practices, and re-establish their cultural heritage. Language immersion schools, cultural centers, and traditional arts programs are springing up globally, often in urban areas where displaced community members have gathered. Legal battles for land rights and self-determination continue in international and domestic courts, often drawing on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which affirms indigenous peoples’ rights to their traditional lands and territories.

The struggle for land is, at its heart, a struggle for identity. As one elder from a displaced community eloquently put it, "Our land is not just dirt; it is our story, our song, our blood, our future. Without it, we are like a river without a source." Understanding the profound and devastating impact of forced relocation on tribal identity is not just an academic exercise; it is a moral imperative. It demands recognition of historical injustices, support for self-determination, and a commitment to protecting the ancestral lands that are, for countless tribal peoples, the very essence of who they are. Only then can healing truly begin, and the uprooted souls find their way back to solid ground.