Echoes in the Sacred Land: The Enduring Impact of Federal Indian Policy on Native American Culture

For centuries, the relationship between the United States federal government and the Indigenous peoples within its borders has been a complex tapestry woven with threads of broken promises, forced assimilation, and, ultimately, a resilient struggle for cultural survival. Federal Indian policy, a constantly evolving and often contradictory set of laws and regulations, has profoundly shaped the cultural landscapes of Native American nations, leaving an indelible mark on everything from language and spiritual practices to social structures and connection to the land. From the era of treaties to the devastating policies of removal and assimilation, and finally to the contemporary push for self-determination, each chapter of federal intervention has reverberated through Native communities, sometimes shattering traditions, but often galvanizing a powerful determination to preserve and revitalize their unique heritage.

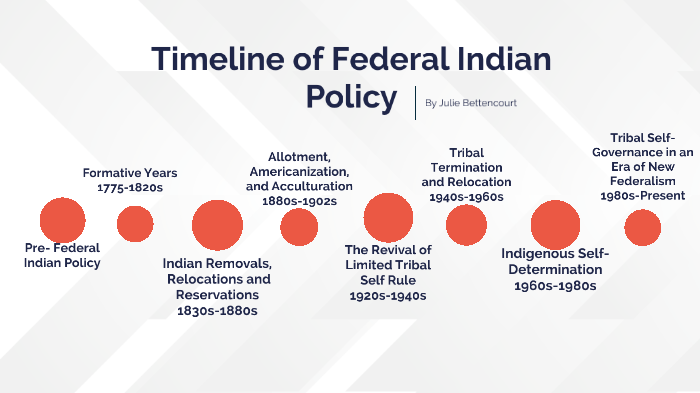

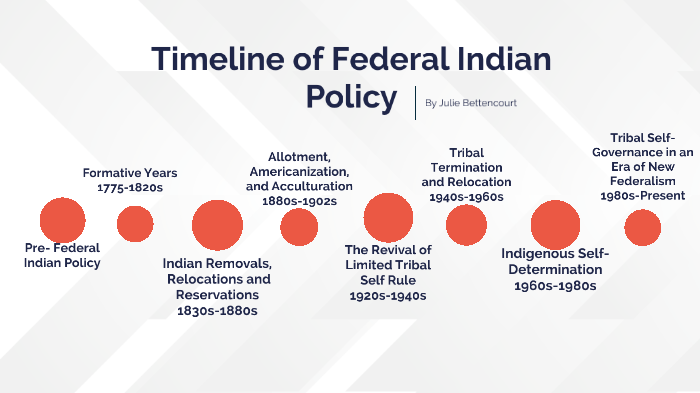

The earliest interactions, following European contact, were often characterized by a semblance of nation-to-nation diplomacy, enshrined in treaties. While these treaties frequently involved coerced land cessions, they at least acknowledged tribal sovereignty, implicitly recognizing distinct cultural and political entities. However, this fragile recognition quickly eroded as the young American republic grew. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, marked a stark turning point. This policy, culminating in the infamous Trail of Tears, forcibly dislocated thousands of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole people from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The cultural impact was catastrophic. Beyond the immense loss of life, the forced removal severed deep spiritual and historical ties to sacred sites, traditional hunting grounds, and agricultural lands. It shattered established social orders, disrupted ceremonial cycles tied to specific geographies, and inflicted deep, intergenerational trauma that continues to resonate today. The land, for Native peoples, is not merely property; it is a living entity, imbued with history, spirituality, and identity. Its forced severance was a wound to the very soul of their cultures.

The mid-19th to early 20th centuries saw the emergence of policies aimed at the outright assimilation of Native Americans into mainstream American society, predicated on the belief that Indigenous cultures were "primitive" and destined to disappear. The Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 was a cornerstone of this assimilationist agenda. This act sought to dismantle communal land ownership, a bedrock of many tribal societies, by dividing reservations into individual parcels (allotments) for Native families. The "surplus" land, often vast tracts, was then sold off to non-Native settlers. The cultural ramifications were devastating. It undermined traditional governance structures based on collective stewardship, fragmented communities, and led to a massive loss of tribal land – from 138 million acres in 1887 to just 48 million by 1934. The shift from communal living to individual landholdings eroded traditional economies, social safety nets, and the very concept of collective identity, pushing many into poverty and further dependence on the federal government.

Perhaps the most insidious and culturally destructive policy was the Indian boarding school system. From the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, hundreds of thousands of Native children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to off-reservation boarding schools. The explicit goal, as articulated by Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was to "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." Children were forbidden to speak their native languages, practice their spiritual traditions, wear traditional clothing, or maintain their cultural hairstyles. Their names were often changed, and they were subjected to harsh discipline, forced labor, and in many documented cases, physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

The cultural wounds inflicted by the boarding school era are profound and enduring. It created a "lost generation" of parents who, having been denied their own cultural upbringing, struggled to transmit traditions to their children. It led to widespread language loss, disrupting the primary vehicle for cultural transmission and oral histories. It fostered deep distrust of authority and created cycles of intergenerational trauma – affecting mental health, family cohesion, and cultural identity for generations. As Native American scholar and activist Zitkala-Ša (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) eloquently wrote of her boarding school experience, "I was as a wee caught in a swiftly moving current, which was taking me away from my dear mother to an unknown country." This sense of being torn from one’s roots, physically and culturally, was a shared experience for countless children.

The mid-20th century brought further policy shifts. The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934 attempted to reverse some of the damage of allotment by ending further land sales and encouraging tribal self-governance. However, even this "reform" was often imposed, requiring tribes to adopt constitutional models that sometimes clashed with their traditional forms of governance. It was a step towards recognizing sovereignty, but still within a framework dictated by federal authority.

This brief period of relative autonomy was followed by another devastating policy: Termination. From 1953 to 1968, the federal government sought to "terminate" its special relationship with tribes, ending federal recognition, services, and protections, and pushing for the assimilation of Native Americans into urban areas. The intent was to end federal "wardship" and make Native Americans full citizens with the same rights and responsibilities as other Americans, but without acknowledging the unique historical context or treaty obligations. The cultural impact was catastrophic for the tribes targeted. For instance, the Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin, once self-sufficient, saw their reservation lands and timber industry privatized, leading to rampant poverty, loss of cultural identity, and a collapse of essential services. Termination was a clear message: the federal government wished to erase the distinct cultural and political status of Native nations.

The pendulum began to swing back towards tribal sovereignty in the 1970s with the Self-Determination Era. Landmark legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 allowed tribes to contract with the federal government to administer their own programs and services, shifting power and control back to tribal governments. This era has been marked by a powerful resurgence of Native American cultures. Tribes are actively engaged in language revitalization programs, establishing tribal colleges, building cultural centers, and reclaiming traditional spiritual practices.

Today, the cultural landscape of Native America is one of immense resilience and revitalization. Tribes are leading efforts to teach endangered languages through immersion schools and master-apprentice programs, recognizing that language is a vital repository of cultural knowledge, worldview, and identity. For example, the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project has, through immense effort, brought their language back from dormancy. Traditional arts, ceremonies, and storytelling are experiencing a vibrant renaissance. Native artists are reinterpreting traditional forms, and Indigenous filmmakers and writers are telling their own stories, challenging stereotypes and celebrating their heritage.

However, the legacy of past policies continues to cast a long shadow. The intergenerational trauma from boarding schools, land dispossession, and termination policies manifests in disproportionately high rates of poverty, health disparities, and social challenges in many Native communities. The fight for the protection of sacred sites, like Bears Ears National Monument or the Black Hills, underscores the ongoing struggle to maintain a spiritual and cultural connection to ancestral lands against development and exploitation.

In conclusion, the impact of federal Indian policy on Native American culture is a testament to both the destructive power of systemic oppression and the indomitable spirit of Indigenous peoples. From the forced migrations that severed ancestral ties to the concerted efforts to eradicate languages and spiritual practices, federal policies have relentlessly attacked the very foundations of Native cultures. Yet, despite these profound challenges, Native American cultures have not only survived but are thriving, demonstrating remarkable adaptability, resilience, and a steadfast commitment to cultural continuity. The ongoing journey of self-determination is a testament to their enduring strength, as they continue to reclaim their narratives, revitalize their traditions, and shape their futures, ensuring that the echoes of their sacred lands and vibrant cultures resonate for generations to come.