Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English about the impact of alcohol on Native American communities, incorporating quotes and interesting facts.

The Silent Scourge and Enduring Spirit: Alcohol’s Complex Legacy in Native American Communities

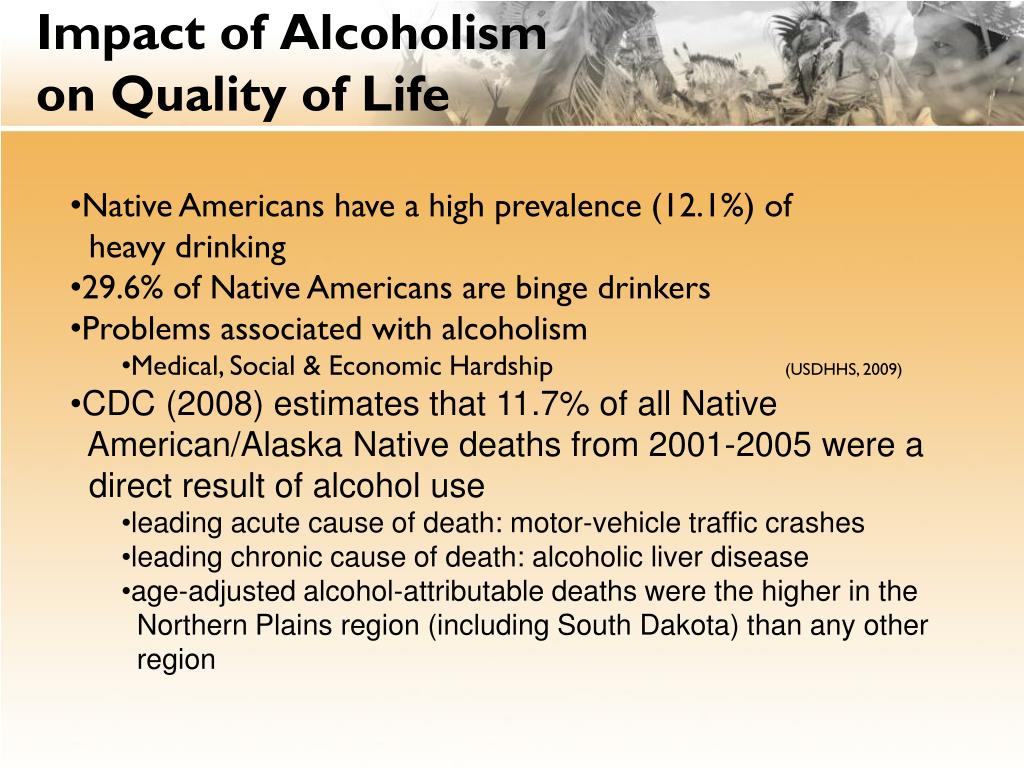

The statistics paint a grim picture: Native Americans and Alaska Natives experience some of the highest rates of alcohol-related deaths and illnesses in the United States. From cirrhosis and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) to accidents and violence, alcohol’s shadow stretches long and dark across many Indigenous communities. Yet, to simply cite these numbers is to miss the profound, multi-layered history, the systemic injustices, and the enduring resilience that defines this complex issue. It is a story not of inherent weakness, but of profound historical trauma, socio-economic disadvantage, and the ongoing struggle for healing and self-determination.

A Legacy Forged in Contact: The Historical Roots

Prior to European contact, alcohol, as it is known today, was largely absent from most Indigenous societies in North America. Where fermented beverages existed, they were typically low in alcohol content and used ceremonially, not for intoxication. The introduction of distilled spirits by European traders and colonizers marked a devastating turning point. Alcohol was often used as a tool of exploitation, facilitating unfair trades for land and resources, and contributing to the disruption of traditional social structures.

The infamous "firewater" myth – the notion that Native Americans have a unique biological susceptibility to alcohol – is a harmful stereotype that has been widely debunked by scientific research. As Dr. Joseph Westermeyer, a psychiatrist specializing in Native American health, noted, "There is no evidence for a genetic predisposition to alcoholism among American Indians." Instead, historical context reveals a more accurate and painful truth: the vulnerability was socio-cultural, not biological. Indigenous communities, with no prior exposure or cultural norms for managing this potent substance, were ill-equipped to handle its devastating effects, especially as their societies were simultaneously being torn apart by disease, warfare, and forced displacement.

The 19th and 20th centuries brought waves of genocidal policies, from forced removal and the destruction of traditional economies to the boarding school era. Children were ripped from their families, forbidden to speak their languages or practice their cultures, and subjected to systemic abuse. This intentional cultural genocide created deep, intergenerational wounds. Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, a Hunkpapa Lakota social worker and scholar, pioneered the concept of "Historical Trauma," defining it as the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experiences. Alcohol, in this context, became a coping mechanism for unbearable pain, a way to numb the trauma of loss – loss of land, language, family, and spiritual connection.

The Intergenerational Echo: Why the Problem Persists

The legacy of historical trauma is not merely an abstract concept; it manifests in tangible ways today. Communities grappling with high rates of poverty, unemployment, inadequate housing, and limited access to quality healthcare and education often see higher rates of substance abuse. These are not coincidences, but direct consequences of centuries of systemic discrimination and underinvestment.

Consider the economic landscape: many reservations are geographically isolated, offering few employment opportunities. The median income for Native American households is significantly lower than the national average, and poverty rates are nearly double. Without economic stability, the stress of daily life can be overwhelming, making the allure of escape through alcohol more potent.

Furthermore, the erosion of traditional cultural practices and spiritual beliefs has left a void. For generations, Indigenous cultures provided robust frameworks for health, community well-being, and individual purpose. The deliberate suppression of these practices removed protective factors that once guided communities. When these anchors are lost, individuals and communities can drift, seeking solace in destructive patterns.

Access to culturally competent healthcare is another critical barrier. Many Native communities, especially those in rural areas, lack sufficient treatment facilities, mental health services, and addiction specialists. Even when services are available, they may not be designed to address the unique needs and cultural perspectives of Indigenous people. A generic 12-step program, while effective for some, might not resonate with someone grappling with the spiritual wounds of historical trauma.

The Devastating Impacts: Health, Family, and Future

The consequences of alcohol abuse ripple through every aspect of Native American life.

Health:

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD): Perhaps one of the most heartbreaking impacts is FASD, a range of conditions caused by prenatal alcohol exposure. Native American communities often experience disproportionately high rates of FASD, leading to lifelong challenges for affected individuals, including cognitive impairments, behavioral problems, and developmental delays. This not only affects the individual but places immense strain on families and tribal resources.

- Liver Disease: Alcohol-related liver disease, including cirrhosis, is a leading cause of death among Native Americans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that alcohol-attributable deaths among American Indians/Alaska Natives were 5.5 times higher than among non-Hispanic whites from 2015-2019.

- Accidents and Violence: Alcohol is a major contributing factor to unintentional injuries, motor vehicle accidents, and violence within communities, including domestic violence and homicides.

Social Fabric:

- Family Breakdown: Alcohol abuse contributes to child neglect, family separation, and the cycle of intergenerational trauma, where children growing up in homes affected by addiction are more likely to struggle with it themselves.

- Youth Suicide: Native American youth face alarmingly high rates of suicide, and alcohol often plays a role in these tragic outcomes, either as a direct cause or as a maladaptive coping mechanism for underlying despair.

- Justice System Involvement: Alcohol-related offenses contribute significantly to the overrepresentation of Native Americans in the criminal justice system, further perpetuating cycles of disadvantage.

Dispelling Myths and Embracing Resilience

It is crucial to reiterate that the narrative of alcohol abuse in Native American communities is not one of inherent biological weakness or cultural deficiency. It is a story of profound historical injustice, systemic inequities, and the insidious ways trauma can manifest across generations. Moreover, it is critical to avoid generalization. Native American communities are incredibly diverse, comprising over 574 federally recognized tribes, each with unique cultures, languages, and experiences. Many Indigenous individuals and communities do not struggle with alcohol, and many more are actively engaged in powerful movements of healing and recovery.

"We are not defined by our trauma," asserts Sarah Deer (Muscogee Nation), a prominent advocate against violence in Indigenous communities. "We are defined by our resilience, our sovereignty, and our determination to heal."

Pathways to Healing and Hope

Despite the immense challenges, Native American communities are at the forefront of developing innovative and culturally grounded solutions to address alcohol abuse. These efforts are rooted in self-determination, cultural revitalization, and a holistic approach to well-being.

Cultural Revitalization: The reclamation of traditional languages, ceremonies, dances, and spiritual practices is proving to be a powerful protective factor. These traditions offer a sense of identity, purpose, and community connection that can counter the feelings of alienation and despair that often fuel addiction. Traditional healing practices, guided by elders and spiritual leaders, provide culturally appropriate pathways to recovery that address not just the addiction, but the underlying trauma.

Community-Led Initiatives: Tribes are establishing their own wellness centers, treatment programs, and youth mentorship initiatives that integrate cultural teachings with modern therapeutic approaches. The Fort Peck Tribes in Montana, for example, have developed comprehensive programs that combine traditional healing ceremonies with counseling and job training. The White Earth Nation in Minnesota has focused on strengthening families through culturally relevant parenting programs.

Addressing Root Causes: Advocates are pushing for policies that address systemic inequities, including increased funding for tribal healthcare, education, and economic development. True healing requires not only individual recovery but also the restoration of sovereign control over resources and the ability to build strong, self-sufficient communities.

Youth Empowerment: Investing in Indigenous youth is paramount. Programs that connect young people with their cultural heritage, provide leadership opportunities, and foster positive peer relationships can build resilience and offer alternatives to substance abuse.

The journey toward healing and recovery from the devastating impact of alcohol on Native American communities is long and arduous. It demands a deep understanding of history, an unwavering commitment to justice, and a profound respect for Indigenous cultures and their inherent wisdom. It is a testament to the enduring spirit of Native peoples that, despite centuries of adversity, they continue to reclaim their health, revitalize their traditions, and forge a path towards a future defined not by trauma, but by strength, sovereignty, and profound healing. The silent scourge may have left deep wounds, but the spirit of resilience, vibrant and unyielding, continues to rise.