The Calculated Discord: How Colonial Powers Mastered Divide and Conquer

The vast, sprawling empires of the colonial era were built not just on military might and economic exploitation, but on a more insidious and enduring strategy: divide and conquer. Faced with numerically superior indigenous populations and the logistical challenges of administering distant lands, colonial powers meticulously engineered schisms, amplified existing tensions, and even fabricated new identities to maintain control, minimize resistance, and consolidate their rule. This calculated discord became the bedrock of their power, leaving a fractured legacy that reverberates across former colonies to this day.

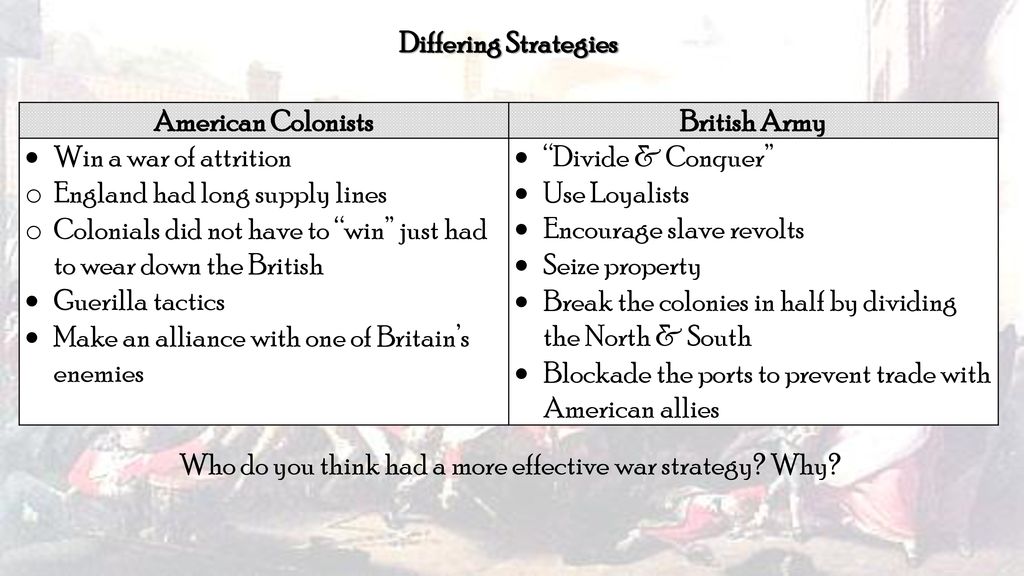

At its core, "divide and conquer" (or divide et impera) is a political and military strategy of gaining and maintaining power by breaking up larger concentrations of power into segments that individually have less power than the one implementing the strategy. In the colonial context, it was a multi-faceted approach, tailored to local conditions but always serving the singular goal of colonial hegemony.

The Logic of Domination: Why Divide?

Colonial administrations were almost always critically understaffed by Europeans. Governing millions with a handful of officials and a modest military contingent was an impossible task without internal allies and internal strife. Direct, brute-force repression was costly, inefficient, and prone to sparking widespread rebellion. By fostering divisions, colonial powers could:

- Prevent United Fronts: A unified resistance, especially across ethnic or religious lines, posed the greatest threat.

- Recruit Local Collaborators: Empowering one group allowed them to be used as proxies against others, creating a local elite loyal to the colonial power.

- Reduce Administrative Burden: Local groups could be made to govern themselves under colonial oversight, often with a greater degree of ‘legitimacy’ than direct foreign rule.

- Justify Intervention: Internal conflicts, often stoked by colonial policies, provided pretexts for further colonial intervention and the assertion of "peacekeeping" authority.

Tactics of Fragmentation: A Colonial Playbook

Colonial powers employed a sophisticated array of tactics to sow discord, often adapting existing social structures to their advantage or inventing new ones.

1. Exacerbating and Codifying Existing Divisions:

Perhaps the most common tactic was to identify and amplify pre-existing ethnic, religious, linguistic, or caste differences. In India, for instance, the British Raj masterfully exploited the Hindu-Muslim divide. While tensions existed prior to British rule, colonial policies systematically deepened them.

"The British policy of ‘divide and rule’ in India was not merely a convenient byproduct of their administration; it was a deliberate strategy," writes historian Bipan Chandra. They introduced separate electorates for Muslims in 1909, effectively institutionalizing religious identity as a political category. They presented themselves as neutral arbiters, but in practice, they often favored one community over another depending on strategic needs, contributing significantly to the eventual partition of India in 1947, a bloody and devastating legacy.

Similarly, the British played off various princely states against each other, ensuring that no single indigenous power could challenge their authority. The caste system, an ancient social hierarchy, was meticulously documented and codified by the British, often rigidifying what had been more fluid social structures, and using it for administrative and census purposes, which further entrenched its divisive nature.

2. Manufacturing New Identities and Hierarchies:

In many parts of Africa, where pre-colonial societies were often organized along fluid clan or lineage lines, colonial powers often "invented" or rigidified "tribal" identities to create manageable administrative units. They would select certain groups, elevate them to positions of authority, and provide them with privileges, thus creating a new, often artificial, hierarchy.

A chilling example is the Belgian administration in Rwanda and Burundi. The Belgians, influenced by pseudo-scientific racial theories, designated the Tutsi as inherently superior to the Hutu, based on physical characteristics and historical narratives. They issued identity cards classifying individuals as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa, a system that had profound and tragic consequences in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. The Tutsi, a minority, were favored in education and administration, creating deep resentment among the Hutu majority, a resentment that was meticulously cultivated and exploited by colonial authorities to ensure a loyal, if resented, proxy.

3. Economic Manipulation and Labor Migration:

Colonial economic policies also served to divide. The British in Malaya (now Malaysia) imported large numbers of Chinese and Indian laborers to work in tin mines and rubber plantations, respectively. This created a multi-ethnic society where different groups were often confined to specific economic sectors and geographical areas. The Chinese became prominent in commerce, the Indians in plantations, and the indigenous Malays were often left in rural agriculture. This segmentation prevented the formation of a unified anti-colonial movement, as different ethnic groups often had different grievances and aspirations, and were sometimes played off against each other in labor disputes or political negotiations.

4. Political Manipulation and Indirect Rule:

The concept of "Indirect Rule," pioneered by the British, particularly in Africa, was a sophisticated form of divide and conquer. Instead of direct administration, colonial powers ruled through existing or newly appointed local chiefs, emirs, or traditional leaders. These local rulers were given power and resources, but their authority ultimately stemmed from the colonial state.

This system had several advantages: it was cheaper to administer, it gave the illusion of local autonomy, and it created a class of indigenous elites whose power and wealth depended on their loyalty to the colonial master. If a local leader became uncooperative, they could be replaced by a more compliant one, or their authority undermined by empowering a rival. This created internal competition and prevented a united front against the colonial power. In Nigeria, for example, the British often favored specific ethnic groups (like the Hausa-Fulani in the North) for administrative roles, creating lasting imbalances and resentments that contributed to post-colonial ethnic tensions and conflicts.

5. Military and Security Apparatus:

Colonial powers often recruited soldiers and police from specific ethnic or religious groups, especially those they deemed "martial races" or those who had been historically marginalized by other local groups. These units were then used to suppress dissent among other indigenous populations. The British Indian Army, for instance, heavily recruited Sikhs, Gurkhas, and Punjabi Muslims, who were then used to maintain order across the subcontinent and beyond. This created a situation where indigenous people were used to subjugate their own kind, deepening divisions and fostering resentment. These forces were often given preferential treatment, further cementing their loyalty to the colonial power and their separation from the general populace.

6. Legal and Educational Segregation:

Separate legal systems for different racial or ethnic groups were common. Europeans often enjoyed a distinct legal code and privileges, while indigenous populations were subject to their own ‘native laws,’ often codified and manipulated by colonial authorities. This created a system of legal inequality that reinforced racial and ethnic hierarchies.

Educational policies also played a divisive role. Colonial powers sometimes established separate schools for different ethnic or religious groups, or designed curricula to reinforce existing social stratifications. In some cases, a small elite was educated in European-style schools to serve the colonial administration, creating a class of "black Englishmen" or "évolués" who were often alienated from their own cultures but not fully accepted by the colonizers.

The Enduring Legacy of Calculated Discord

The impact of these divide and conquer tactics extended far beyond the end of formal colonial rule. When independence movements swept across the globe, the newly formed nations often inherited borders drawn arbitrarily by colonial powers, encompassing diverse and often antagonistic groups whose divisions had been systematically deepened.

The artificial hierarchies and manufactured identities created under colonial rule became deeply entrenched, fueling post-colonial conflicts. The Rwandan Genocide, the Nigerian Civil War (Biafra), the ongoing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the persistent ethnic tensions in many parts of South Asia and Southeast Asia are stark reminders of how colonial policies of division continued to wreak havoc long after the colonizers had departed.

The arbitrary borders, the unequal distribution of resources, the resentment between groups, and the fragility of national identities in many former colonies can be directly traced back to the calculated discord sown by colonial powers. While they presented themselves as bringing "civilization" and "order," their true legacy was often one of profound fragmentation, leaving a bitter harvest of mistrust and instability that continues to challenge the pursuit of peace and development in the post-colonial world. Understanding this history is crucial, not merely for academic insight, but for grappling with the complex realities of contemporary global politics and the enduring scars of an imperial past.