Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English on how ancient Native Americans adapted to deserts.

Echoes in the Dust: How Ancient Native Americans Mastered the Desert

The desert, with its searing sun, parched earth, and often brutal temperature swings, presents one of Earth’s most unforgiving environments. For millennia, it has tested the limits of human endurance, pushing life to its absolute brink. Yet, against this stark backdrop, ancient Native American communities not only survived but thrived, carving out a rich existence through an unparalleled blend of ingenuity, deep ecological knowledge, and profound spiritual connection to the land. Their story is not one of mere survival, but of a sophisticated mastery over an environment that often appeared to offer nothing.

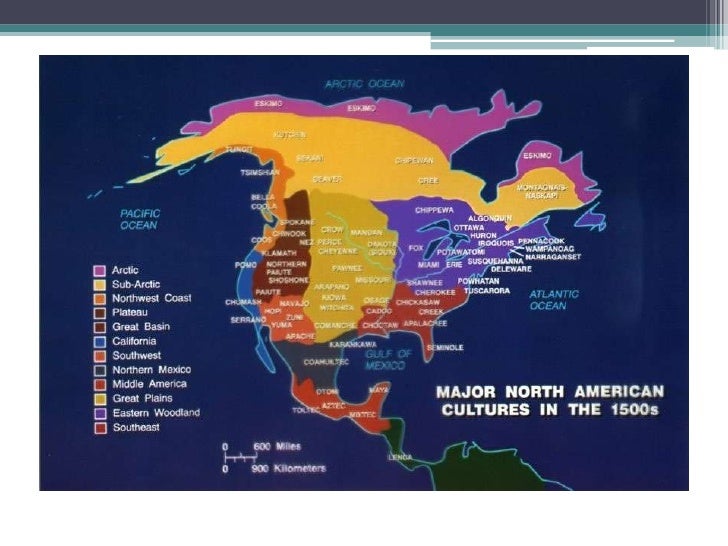

From the Sonoran Desert’s saguaro-studded expanse to the high-altitude aridity of the Great Basin, diverse indigenous groups developed a tapestry of adaptive strategies that allowed them to flourish. These adaptations were not monolithic; they varied significantly depending on the specific desert ecosystem, available resources, and cultural practices of groups like the Hohokam, Ancestral Puebloans, Fremont, Cahuilla, and countless others. What unites their experiences, however, is a testament to human resilience and a blueprint for sustainable living that resonates powerfully even today.

The Quest for Water: The Desert’s Lifeline

Perhaps the most critical challenge in any desert environment is the acquisition and management of water. Ancient Native Americans transformed this scarcity into an art form, developing techniques that ranged from monumental engineering feats to an intimate understanding of microclimates and plant hydrology.

The Hohokam people, flourishing in what is now central Arizona between 300 and 1450 CE, stand as a monumental example of hydraulic engineering in the desert. Their sophisticated irrigation systems, fed by the Salt and Gila Rivers, stretched for hundreds of miles, diverting water through a complex network of canals to cultivate vast fields of corn, beans, and squash. Some of these canals were up to 10 feet deep and 30 feet wide, requiring immense communal effort and precise engineering. "The Hohokam did not just farm in the desert; they fundamentally reshaped it," notes anthropologist Dr. Sarah B. Johnson, "demonstrating a level of hydraulic ingenuity unmatched in North America until modern times." Their systems were so efficient that parts of modern Phoenix’s irrigation infrastructure follow the paths of ancient Hohokam canals.

Beyond large-scale irrigation, other groups devised equally clever methods. In drier regions, communities like the Ancestral Puebloans (often referred to as Anasazi) constructed elaborate systems for capturing and storing rainwater and snowmelt. They built check dams and terraced fields to slow runoff, allowing precious moisture to soak into the soil. At sites like Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, small reservoirs and cisterns carved into rock or constructed from masonry collected water for drinking and domestic use. The famous cliff dwellings themselves offered protection from the elements and often incorporated natural springs or seeps directly into their architecture.

For nomadic or semi-nomadic groups, the search for water was a constant journey. They learned to identify subtle signs of underground springs, dig shallow wells in dry streambeds (known as tinajas), and even collect dew. Many understood that certain plants, like barrel cacti and agave, held significant amounts of water and could be tapped in emergencies. Travel often occurred during the cooler night hours, conserving precious bodily fluids.

Harnessing the Desert’s Pantry: Subsistence Strategies

The desert, seemingly barren, is in fact a diverse ecosystem brimming with edible and useful plants and animals, provided one possesses the knowledge to find and prepare them. Ancient Native Americans were master botanists and hunters, transforming the desert’s harsh bounty into a reliable food source.

Hunting focused on smaller, more elusive game adapted to the desert, such as rabbits, hares, rodents, and various birds. Larger game like deer and bighorn sheep were pursued opportunistically in areas where they congregated, often near water sources. Traps, nets, and bows and arrows were essential tools in these endeavors.

However, it was their extensive knowledge of ethnobotany that truly defined desert subsistence. Plants like the mesquite tree were invaluable. Its pods could be ground into a nutritious flour, rich in protein and carbohydrates, and stored for long periods. The pods could also be fermented to create a beverage. The saguaro cactus provided fruit in late summer, a crucial seasonal harvest. This fruit was eaten fresh, dried, or processed into syrup and jam. The prickly pear cactus offered edible pads (nopales) and sweet fruit (tunas). Agave, another cornerstone, provided not only a source of sugar but also fibers for clothing and tools, and its heart could be roasted into a nutrient-rich food.

"Every plant had a purpose, every animal a role in the desert’s intricate web," explains Dr. Anya Sharma, an archaeologist specializing in indigenous foodways. "Their diet was incredibly diverse, reflecting a profound understanding of the desert’s seasonal cycles and the nutritional properties of its flora and fauna." This deep knowledge allowed them to not only find food but also to manage resources sustainably, ensuring future harvests. Techniques for drying, smoking, and storing foods in cool, dry caches were essential for surviving lean periods.

Shelter and Architecture: Beating the Heat and Cold

Desert temperatures can swing dramatically, from scorching daytime highs to freezing nights. Ancient Native Americans engineered shelters that provided crucial protection from both extremes, using locally available materials and intelligent design principles.

Adobe construction, perfected by groups like the Ancestral Puebloans and later adapted by others, is a prime example. Made from earth, water, and organic materials like straw, adobe walls possess high thermal mass. They slowly absorb heat during the day, keeping interiors cool, and then radiate that stored heat slowly through the night, providing warmth. The famous multi-story pueblos of the Southwest are architectural marvels, designed with small windows, thick walls, and often built into south-facing cliffs or rock overhangs to maximize solar gain in winter and shade in summer.

Pit houses, common across many desert cultures, involved excavating a shallow pit and then constructing a roof structure, often with a central smoke hole. These semi-subterranean dwellings leveraged the earth’s natural insulating properties, remaining cooler in summer and warmer in winter than above-ground structures.

For more nomadic groups, temporary shelters like ramadas (open-sided, flat-roofed structures) provided essential shade during the day, allowing air to circulate. Caves and rock shelters offered natural protection and were often enhanced with simple walls or windbreaks. The orientation of dwellings was also critical, often facing away from the prevailing sun or wind, or strategically positioned to catch cooling breezes.

Tools, Technology, and Material Culture

Survival in the desert demanded specialized tools and technologies. Ancient Native Americans developed a sophisticated material culture tailored to their environment.

Pottery was vital for storing water, cooking, and holding processed foods. The porous nature of unglazed pottery allowed for evaporative cooling, keeping water inside refreshingly cool. Baskets, woven with incredible skill from materials like yucca and willow, were used for gathering, carrying water (some were watertight through intricate weaving and pitch lining), and even cooking with hot stones.

Grinding stones (metates and manos) were essential for processing tough desert plants like mesquite pods and corn kernels into flour. Obsidian and chert were flaked into sharp tools for hunting, butchering, and crafting. Plant fibers, particularly from yucca and agave, were twisted into strong cords for nets, traps, and weaving into sandals, mats, and even durable clothing. Animal hides, when available, were processed for warmer clothing, blankets, and carrying bags.

Social Organization and Spiritual Connection

Beyond technological prowess, the adaptive success of ancient Native Americans was deeply rooted in their social structures and worldview. Communal effort was essential for large-scale projects like irrigation canals or pueblo construction. Knowledge—about water sources, plant locations, animal behavior, and weather patterns—was meticulously passed down through generations via oral tradition, ceremonies, and practical instruction. Elders held immense respect as repositories of this vital information.

Perhaps most profoundly, these cultures harbored a deep spiritual connection to the land. The desert was not a hostile enemy to be conquered, but a living entity, a sacred landscape that demanded respect and reciprocity. Ceremonies for rain, bountiful harvests, and successful hunts were integral to their lives, reinforcing their connection to the natural world and their place within it. This holistic understanding fostered sustainable practices, ensuring that resources were managed not just for the present generation, but for all future generations.

A Legacy of Resilience

The adaptations of ancient Native Americans to the desert are more than just historical footnotes; they are enduring lessons in resilience, ingenuity, and sustainable living. Their ability to transform a seemingly inhospitable landscape into a thriving home speaks volumes about the human spirit and the power of deep ecological knowledge. As modern societies grapple with climate change, water scarcity, and environmental degradation, the echoes of their desert mastery offer invaluable wisdom—a timeless reminder that harmony with nature is not just possible, but essential for survival. Their legacy stands tall, like a saguaro against the setting sun, a monument to human ingenuity etched into the very dust of the desert.