Guardians of the Mesas: The Enduring Cultural Traditions of the Hopi Nation

By

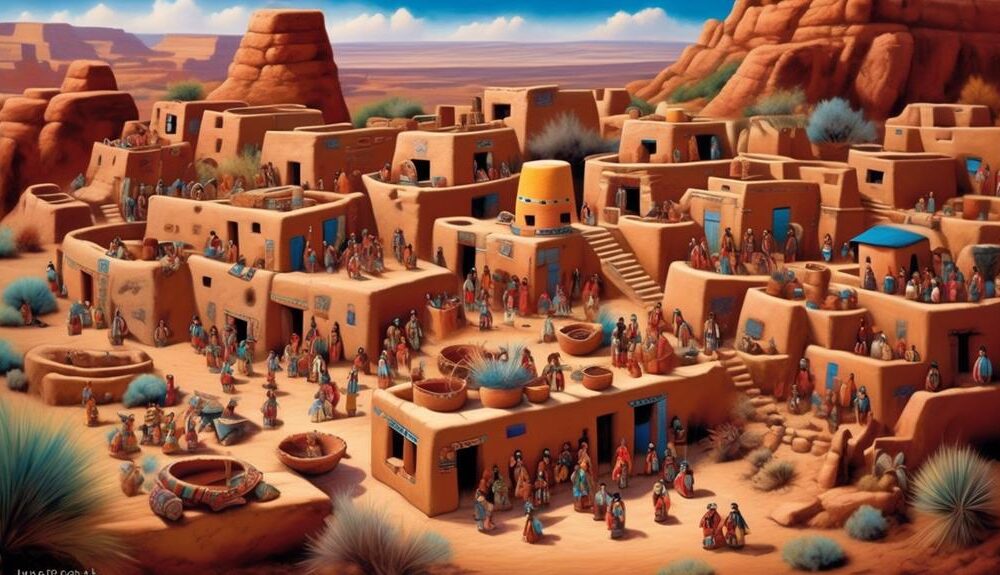

High above the Arizona desert, where the vast, ochre landscape meets an endless sky, rise three ancient mesas. Perched atop these formidable natural fortresses are the villages of the Hopi, a people whose name, "Hopituh Shi-nu-mu," translates to "The Peaceful People." For millennia, the Hopi have meticulously cultivated not just their fields of drought-resistant corn, but also a profound spiritual and cultural heritage that remains remarkably vibrant in the face of modernity. Their reservation, a land of stark beauty and deep spiritual resonance, is a living testament to an unbroken lineage stretching back to time immemorial, offering a rare glimpse into a worldview deeply rooted in harmony, humility, and an intricate connection to the earth and cosmos.

The Hopi are unique among Native American tribes for their continuous occupation of their ancestral lands, with some villages, like Old Oraibi on Third Mesa, claiming to be the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in North America, dating back to at least 1100 AD. This extraordinary longevity is not merely a historical footnote; it is the bedrock of their identity, informing every aspect of their cultural traditions. Unlike many tribes forced into multiple relocations, the Hopi have maintained an intimate, uninterrupted relationship with their sacred landscape, which they believe was given to them by Maasaw, the caretaker of the Earth.

At the heart of Hopi culture lies a complex spiritual system, centered on the Katsinam (often pluralized in English as "Kachinas"). These are not gods, but spiritual beings, messengers from the spirit world who embody the benevolent forces of nature, ancestral spirits, and the cycles of life. They appear to the Hopi during a ceremonial cycle that begins after the winter solstice and concludes in mid-July. During this period, masked dancers, representing specific Katsinam, emerge from underground ceremonial chambers known as kivas, bringing blessings, rain, and fertility to the Hopi people and their crops.

"For the Hopi, the Katsinam are living entities," explains one elder, whose name is withheld out of respect for Hopi tradition regarding sensitive religious topics. "They are not simply men in masks; they are the embodiment of those spirits. When they dance in our plazas, they bring the spirit world directly into our lives, reminding us of our covenant with the Creator and our responsibilities to the earth."

The intricate carvings known as Katsina tihu (often called "Katsina dolls" by outsiders) are not toys, but sacred instructional objects given to Hopi children, particularly girls, during ceremonies. These figures serve as visual aids, helping to teach the young about the different Katsinam, their characteristics, and their significance within the Hopi cosmology. Each tihu is meticulously carved from cottonwood root and painted with symbolic colors and designs, reflecting the specific attributes of the Katsina it represents.

Beyond the ceremonial cycle, the land itself is a sacred text for the Hopi. Their agricultural practices, particularly dryland farming, are a marvel of adaptation and spiritual dedication. Unlike most modern agriculture, Hopi farming relies entirely on natural rainfall and runoff, without irrigation. The staple crop, corn, is not just food; it is a sacred relative, embodying life itself. Different colors of corn—blue, white, yellow, red, and the rare black—hold distinct spiritual meanings and are used in various ceremonies and daily life.

"Our corn is our life," states a farmer tending his field on Second Mesa. "It connects us to our ancestors, to the rain, to the sun. Every seed planted is a prayer, every harvest a blessing. It teaches us patience, resilience, and the power of cooperation." This deep connection to the land is not merely practical; it is a spiritual imperative, a covenant to care for the earth that sustains them. The Hopi believe their continued ceremonial observances are not just for their own well-being, but for the balance and harmony of the entire world.

The social structure of the Hopi is equally intricate and deeply traditional. Organized into matrilineal clans, descent and property pass through the mother’s line. Each clan has specific responsibilities within the ceremonial cycle and plays a vital role in village governance. The village chief, or Kikmongwi, holds a spiritual leadership role, guided by ancient prophecies and the well-being of the community. Decision-making is often a lengthy, consensual process, reflecting the Hopi emphasis on harmony and collective responsibility over individual ambition.

Hopi artistry is another vibrant expression of their culture. Pottery, particularly the "Sikyatki Revival" style championed by the legendary Nampeyo of Hano in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is renowned for its elegant forms and intricate designs inspired by ancient shards. Basketry, with its vibrant colors and geometric patterns, comes in various forms, including wicker plaques and coiled plaques, each carrying cultural significance. Silverwork, introduced later, has also become a distinctive Hopi art form, often featuring overlay techniques and designs derived from Katsinam and other traditional symbols. These crafts are not merely aesthetic; they are living traditions, passed down through generations, embodying cultural narratives and providing economic sustenance.

The Hopi language (Hopiikwa), part of the Uto-Aztecan family, is another critical pillar of their cultural identity. It is a language rich in nuance, reflecting their unique worldview and deep understanding of the natural world. Efforts to preserve and revitalize the language are ongoing, with schools and community programs working to ensure that future generations continue to speak the language of their ancestors. "To lose our language is to lose a part of our soul," emphasizes a language teacher. "Our language carries our history, our ceremonies, our way of thinking about the world. It is irreplaceable."

Despite their profound resilience, the Hopi Nation faces significant challenges in the 21st century. Economic development, the allure of modern society, and external pressures threaten to erode traditional ways of life. Tourism, while offering economic opportunities, must be carefully managed to protect the sacredness and privacy of ceremonies. Water rights, a perennial issue in the arid Southwest, remain a critical concern, impacting both agriculture and daily life. The younger generation grapples with balancing the demands of modern education and careers with their responsibilities to traditional practices.

Yet, the Hopi continue to demonstrate extraordinary strength and adaptability. Cultural preservation programs, youth engagement initiatives, and the unwavering commitment of elders ensure that the ancient wisdom continues to be transmitted. The Hopi Cultural Center, with its museum, motel, and restaurant on Second Mesa, serves as a vital resource for both Hopi people and respectful visitors, offering insights into their history and traditions.

For those wishing to visit the Hopi Reservation, respect is paramount. Photography and recording of any kind are strictly prohibited in the villages and at ceremonies. Permission must always be sought before entering private homes or even engaging in conversation. Many villages prefer that visitors explore with a Hopi guide, who can offer context and ensure proper etiquette. The Hopi are a welcoming people, but their hospitality comes with an expectation of reverence for their sacred traditions and their way of life.

In a world increasingly characterized by rapid change and cultural homogenization, the Hopi Nation stands as a powerful reminder of the enduring strength of tradition, the profound wisdom embedded in indigenous knowledge, and the vital importance of living in harmony with the natural world. Their continued existence, their vibrant ceremonies, their ancient villages, and their unwavering commitment to their spiritual path are not just a legacy for their own people; they are a profound gift to humanity, a living testament to the possibility of a peaceful and balanced existence on Earth. The guardians of the mesas continue their vigil, watching over not just their ancestral lands, but also the ancient wisdom that holds lessons for us all.