The Unseen Architect: Squanto, Plymouth, and the Genesis of a Nation

The story of the Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony, often distilled into idyllic images of the first Thanksgiving, is one of desperate survival, unwavering faith, and the improbable genesis of a nation. Yet, beneath the veneer of familiar tales lies a narrative far more complex, a testament to resilience, betrayal, and the profound, often tragic, collision of worlds. At the heart of this intricate tapestry stands Tisquantum, known to history as Squanto, a figure whose unique trajectory made him an indispensable, albeit controversial, architect of the struggling colony’s early success. His life, marked by abduction, displacement, and an almost miraculous return, is not merely a footnote but a foundational chapter in the American story.

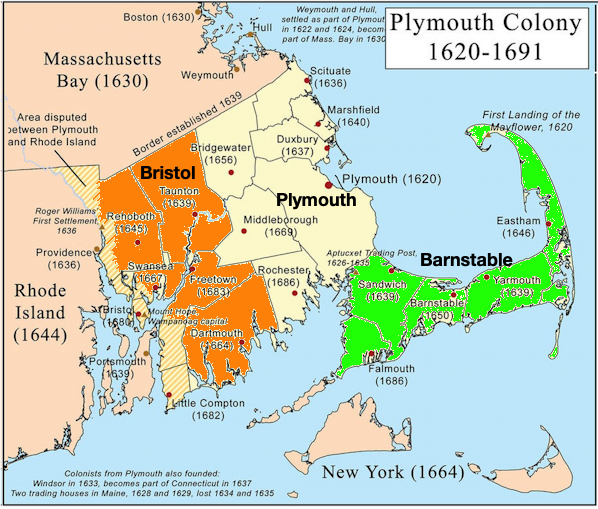

The year 1620 saw the arrival of the Mayflower in what is now Massachusetts, bearing a group of English Separatists seeking religious freedom. Their chosen destination, "Plimoth" in the New World, was no untouched wilderness. It was the ancestral home of the Patuxet people, a vibrant community within the larger Wampanoag Confederacy. But the Pilgrims found not a bustling village, but an eerie, deserted landscape marked by abandoned fields and the bones of a vanished people. A devastating plague, likely brought by earlier European explorers, had swept through the region just a few years prior, decimating the Patuxet and other coastal tribes. This grim reality would prove to be a crucial, albeit tragic, prelude to the Pilgrims’ survival.

Before the Mayflower ever sighted Cape Cod, Tisquantum’s life had already taken a turn more dramatic than any Pilgrim could imagine. Born into the Patuxet tribe around 1580, his world was irrevocably altered in 1614 when he was abducted by Thomas Hunt, an English sea captain. Hunt, sailing under Captain John Smith, lured Squanto and twenty-three other Native Americans onto his ship under false pretenses, then sailed them to Malaga, Spain, to sell them into slavery. Fortuitously, Squanto was rescued by local friars who intended to convert him to Christianity. From Spain, he eventually made his way to London, where he learned English and gained an invaluable, albeit brutal, education in European customs and the ways of the world.

His journey home was protracted and fraught with peril. He returned to North America in 1619, first to Newfoundland, then back to his ancestral lands with explorer Ferdinando Gorges. What he found upon his return must have been a crushing blow: his entire village, the Patuxet, had been wiped out by the plague. He was, in essence, a man without a tribe, a survivor in a landscape haunted by ghosts. This profound loss undoubtedly shaped his motivations and his subsequent interactions with the newly arrived English.

The Pilgrims, meanwhile, were enduring a brutal first winter. More than half of the 102 passengers died from scurvy, pneumonia, and other diseases. They were ill-prepared for the harsh climate, unfamiliar with the local flora and fauna, and struggling to cultivate crops in the unfamiliar soil. Their survival hung by a thread, and their relationship with the indigenous peoples was one of mutual suspicion and cautious observation.

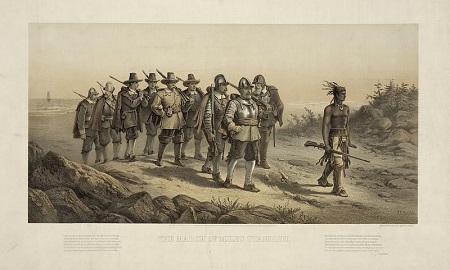

The turning point came in March 1621, when a Native American named Samoset, an Abenaki chief who had learned some English from fishermen, walked into the Pilgrim settlement, astonishing them by greeting them in their own tongue. Samoset served as an initial intermediary, and a few days later, he returned with Tisquantum. This moment marked the true beginning of the Plymouth Colony’s improbable survival.

Squanto was not merely an interpreter; he was a living bridge between two vastly different worlds. Governor William Bradford, in his seminal work Of Plimoth Plantation, famously described Squanto as "a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation." This sentiment, while reflecting Bradford’s religious perspective, underscored Squanto’s immediate and profound impact.

Squanto taught the struggling Pilgrims how to survive in their new environment. He showed them how to cultivate native corn (maize), advising them to plant it with fish as fertilizer, a technique that significantly improved yields. He guided them to fertile fishing grounds, taught them how to hunt local game, identify edible wild plants, and distinguish between poisonous and medicinal herbs. Without his expertise, the Pilgrims’ agricultural endeavors would likely have failed, leading to further starvation.

Beyond survival skills, Squanto played a critical role in diplomacy. He facilitated the crucial peace treaty between the Pilgrims and Massasoit Ousamequin, the sachem (chief) of the Wampanoag Confederacy. Massasoit, whose people had also suffered from the plague and faced threats from rival tribes like the Narragansett, saw the potential for a strategic alliance with the well-armed English. The treaty, negotiated through Squanto, established a fragile but vital peace that would last for over 50 years. It stipulated mutual defense, non-aggression, and peaceful trade – a remarkable achievement in an era of often-violent encounters.

This newfound cooperation culminated in the iconic harvest celebration of autumn 1621, often romanticized as the "First Thanksgiving." For three days, Pilgrims and Wampanoag, including Massasoit and 90 of his men, feasted together on wild fowl, deer, and the fruits of their successful harvest. It was a moment of rare cross-cultural harmony, a testament to Squanto’s pivotal role in forging understanding and mutual respect, however temporary.

Yet, Squanto’s story is not without its shadows. His unique position as the sole Patuxet survivor, coupled with his fluency in English and knowledge of both cultures, gave him immense, perhaps intoxicating, power. He began to exploit this, sometimes playing the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag against each other. He reportedly told the Pilgrims that Massasoit was secretly plotting against them, and conversely, he spread rumors among the Wampanoag that the English harbored disease in their storage pits and could unleash it at will. His aim, it seems, was to elevate his own status and influence, perhaps even to re-establish himself as a leader.

Massasoit eventually became aware of Squanto’s manipulations and demanded his execution under the terms of the treaty, which stipulated that offenders would be handed over for punishment. Governor Bradford, recognizing Squanto’s continued value to the colony, skillfully evaded Massasoit’s demands, though he acknowledged Squanto’s "pride and inconstancy." This episode highlights the perilous tightrope Squanto walked and the ethical complexities of his position. He was a survivor, an opportunist, and a man deeply affected by the loss of his people, navigating a treacherous new world order.

Squanto died in November 1622, while guiding Governor Bradford on an expedition to trade for corn with other tribes. He succumbed to a "native fever" (possibly smallpox or another European disease) and, according to Bradford, requested that the Governor pray for him, asking "to go to the Englishmen’s God." His death deprived the Pilgrims of their most crucial interpreter and guide, though others, like Hobomok, a Wampanoag warrior who had lived among the Pilgrims, stepped into the breach.

Squanto’s legacy is multifaceted and deeply significant. He is a tragic figure, a man caught between two worlds, irrevocably changed by European contact, and ultimately instrumental in the survival of those who would eventually displace his people. His story is a powerful reminder that the early encounters between Europeans and Native Americans were not monolithic. They involved individuals with complex motivations, navigating treacherous landscapes of cultural difference, disease, and shifting power dynamics.

The Plymouth Colony, thanks in no small part to Squanto, survived its precarious early years. It laid the groundwork for future English settlements and the eventual formation of the United States. But the peace he helped broker was ultimately fragile. As more English settlers arrived, land disputes and cultural misunderstandings escalated, eventually leading to King Philip’s War (1675-1678), a devastating conflict that largely extinguished Native American sovereignty in southern New England.

Today, Squanto remains an enduring symbol. He represents the possibility of cross-cultural exchange and mutual aid, but also the profound trauma of colonization, the loss of indigenous life, and the moral ambiguities inherent in historical narratives. His life stands as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, the power of knowledge, and the often-unseen hands that shape the course of history, reminding us that the foundations of nations are rarely as simple or as pristine as our myths suggest. The story of Plymouth Colony, without the full, complicated truth of Tisquantum, remains incomplete. He was not just a guide; he was, for a fleeting, critical moment, the very lifeline of a nascent society.