The Unconquered Spirit: Native American Resilience in Colonial Times

The conventional narrative of European colonization often casts Native American peoples as passive victims, swept aside by the tide of "progress" and superior technology. While the devastation wrought by disease, warfare, and land dispossession was undeniably catastrophic, this simplified portrayal overlooks a profound and crucial counter-narrative: one of extraordinary resilience, strategic resistance, and an enduring spirit that refused to be extinguished. From the very first European footprints on their ancestral lands, Indigenous nations across North America actively fought, adapted, negotiated, and persisted, shaping the colonial landscape in ways often unacknowledged. Their history during this tumultuous era is not merely a tale of suffering, but a powerful testament to human tenacity, ingenuity, and the unyielding will to survive.

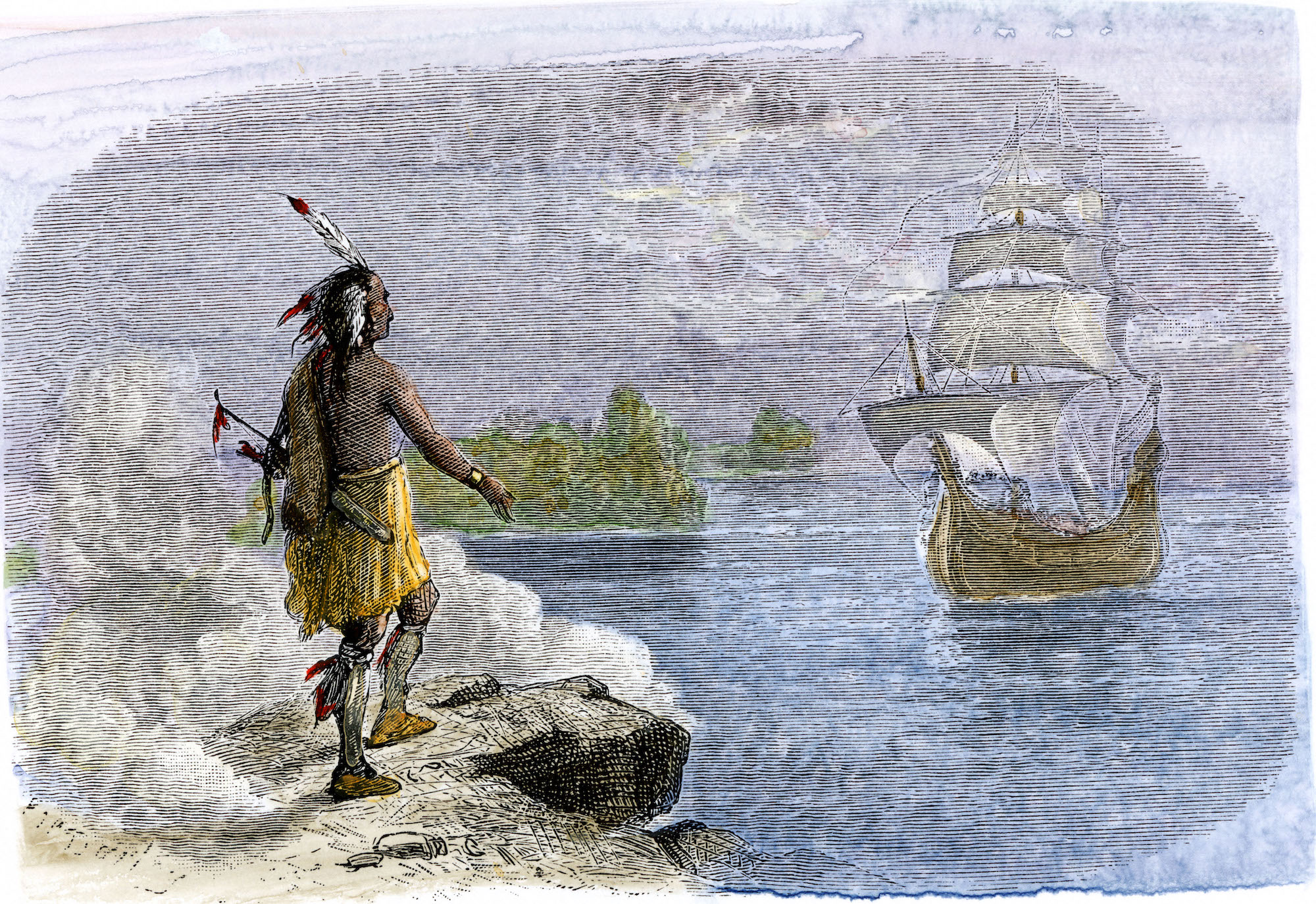

When European explorers and settlers first arrived, they encountered not an empty wilderness, but a continent teeming with diverse, sophisticated societies. From the agricultural prowess of the Mississippian cultures to the complex political structures of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, Native peoples possessed highly developed systems of governance, trade, spiritual belief, and ecological knowledge. Initial encounters were often characterized by a mix of curiosity, trade, and cautious diplomacy. However, the Europeans’ insatiable demand for land, resources, and labor, coupled with their ethnocentric belief in their own cultural and religious superiority, quickly led to escalating conflicts.

One of the most immediate and devastating blows to Native communities was not the sword, but the invisible enemy: Old World diseases. Lacking immunity to smallpox, measles, influenza, and other pathogens, Indigenous populations experienced demographic catastrophes on an unprecedented scale. Scholars estimate that up to 90% of Native populations perished in some regions following initial contact, turning thriving villages into ghost towns and shattering social structures. Entire communities vanished, their knowledge and traditions lost forever. Yet, even in the face of such apocalyptic decimation, the survivors demonstrated an astonishing capacity for adaptation. They reformed alliances, absorbed remnants of shattered groups, and innovated new ways of communal living to rebuild a semblance of stability. This ability to grieve, adapt, and reconstruct was an early, profound demonstration of their indomitable spirit.

Beyond biological warfare, direct military resistance became a defining feature of the colonial period. Native nations were not easily conquered; they fought fiercely for their homelands, their sovereignty, and their way of life. One of the most spectacular successes of Indigenous resistance was the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Under the leadership of Popé, a Tewa religious leader, the various Pueblo peoples of what is now New Mexico united in a meticulously planned uprising against Spanish colonial rule. In a coordinated assault, they drove the Spanish completely out of New Mexico, reclaiming their ancestral lands and religious practices for over a decade. This remarkable victory, achieved through inter-tribal unity and strategic brilliance, stands as a powerful example of successful Indigenous self-liberation, proving that European power was far from absolute. As the Spanish governor, Antonio de Otermín, recounted the devastating defeat, it underscored the unified and determined resolve of the Pueblo peoples.

Further east, in New England, King Philip’s War (1675-1678), led by Metacom (known to the English as King Philip), sachem of the Wampanoag, demonstrated a similar, if ultimately tragic, determination. Metacom forged a broad alliance of Native tribes to resist encroaching English settlements and defend their dwindling lands. The war was one of the bloodiest in American history, proportionally, with both sides suffering immense casualties. Though the Native alliance was eventually defeated, and Metacom was killed, the war showcased the fierce resolve of Indigenous peoples to fight for their existence against overwhelming odds. It shook the foundations of colonial power and left a lasting legacy of defiance.

Later, in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes region, Pontiac’s War (1763-1766) erupted in the wake of the French and Indian War. Led by Pontiac, an Ottawa chief, this pan-tribal confederation sought to drive the British out of their territories following the departure of their French allies. Pontiac articulated a powerful message of Native unity and cultural revitalization, urging his people to reject European goods and influences. His forces captured several British forts and besieged others, again demonstrating the capacity for coordinated resistance against a formidable European power. These military struggles were not acts of desperation but calculated strategies to protect their autonomy and cultural integrity.

Beyond direct warfare, Native American nations employed sophisticated diplomatic acumen and strategic alliances as powerful tools of resilience. They were not monolithic entities but complex nations with their own rivalries, alliances, and political objectives. Many Indigenous groups adeptly played European powers – the French, British, and Spanish – against each other, leveraging their strategic positions to gain favorable trade terms, military support, or simply to buy time.

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy stands as a prime example of such diplomatic genius. Comprising the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations (later joined by the Tuscarora), the Haudenosaunee had established a powerful political and military confederacy long before European arrival, governed by the "Great Law of Peace." During the colonial era, they became a crucial third force in North America, navigating the shifting alliances between the French and British empires. Their strategic location, disciplined warriors, and shrewd diplomacy allowed them to maintain significant influence and territorial control for centuries, often dictating terms to European governors rather than being dictated to. Their ability to forge alliances, negotiate treaties, and maintain their sovereignty in the face of immense pressure is a testament to their political sophistication and resilience.

Cultural and spiritual persistence formed another vital layer of Native American resilience. Even as missionaries sought to convert them and colonial policies aimed to erase their traditions, Indigenous peoples fiercely guarded their languages, ceremonies, oral histories, and spiritual beliefs. They adapted by sometimes outwardly adopting aspects of European culture while inwardly preserving their core identity. Syncretism – the blending of traditional beliefs with new influences – allowed for the evolution of spiritual practices that retained Indigenous essence while incorporating new elements. The maintenance of traditional clan systems, kinship networks, and communal decision-making processes, even under duress, ensured the continuity of their social fabric. Oral traditions, passed down through generations, became vital repositories of history, law, and identity, ensuring that the wisdom of ancestors and the stories of resistance were never forgotten.

Economically, Native Americans also demonstrated remarkable adaptability. They integrated European goods like firearms, metal tools, and textiles into their existing trade networks, often becoming key partners in the fur trade. This was not a passive adoption but an active engagement that often influenced European economies. While some became dependent on European goods, many also maintained their traditional subsistence patterns – hunting, fishing, gathering, and agriculture – ensuring food security and cultural continuity. They introduced Europeans to vital crops like corn, beans, and squash, which fundamentally transformed global agriculture. This exchange was a two-way street, where Native ingenuity and knowledge were as vital as European commodities.

The story of Native American resilience during colonial times is a complex tapestry woven with threads of tragedy, triumph, adaptation, and unwavering spirit. It challenges the simplistic narratives of inevitable conquest and reveals a dynamic, active Indigenous presence that continually pushed back against the forces of colonialism. From the devastating initial impact of disease to the fierce battles for land and sovereignty, from the sophisticated diplomacy of powerful confederacies to the quiet persistence of cultural and spiritual traditions, Native peoples were never passive victims. They were agents of their own history, who, against staggering odds, found ways to survive, resist, and adapt.

This legacy of resilience extends far beyond the colonial era, continuing to inspire contemporary struggles for self-determination, land rights, and cultural revitalization. Understanding this history is not just about correcting past wrongs; it is about recognizing the enduring strength of Indigenous nations and acknowledging their profound contribution to the complex tapestry of North American history. The unconquered spirit of Native Americans in colonial times is a powerful reminder of humanity’s capacity for endurance and the unyielding pursuit of freedom and cultural integrity.