The Unsettling March: A History of the Indian Removal Act of 1830

The history of the United States is often painted with broad strokes of progress, liberty, and the pursuit of a more perfect union. Yet, beneath this triumphant narrative lies a darker, more complex tapestry, woven with threads of dispossession, broken promises, and profound human suffering. Central to this difficult truth is the Indian Removal Act of 1830, a legislative landmark that codified the forced relocation of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to territories west of the Mississippi River. Far from a simple administrative act, it was the culmination of decades of land hunger, racial prejudice, and a deeply flawed interpretation of national destiny, forever scarring the relationship between the U.S. government and Indigenous peoples.

The seeds of removal were sown long before 1830. From the earliest days of European colonization, the presence of Native Americans presented a fundamental obstacle to the expansionist ambitions of settlers. While early colonial policies sometimes involved treaties and land purchases, these were often coercive and rarely honored in the long term. Following the American Revolution, the nascent United States inherited this complex legacy. President Thomas Jefferson, a figure often celebrated for his enlightenment ideals, grappled with the "Indian Question." His vision, though seemingly benevolent, offered a stark choice: assimilate into American society by adopting farming, Christianity, and private property ownership, or be removed beyond the reach of white settlement. "The ultimate point of rest and happiness for them," Jefferson wrote in 1803, "is to be found in the re-union with their red brethren on the Mississippi." This paternalistic view paved the way for future policies, framing removal not as an act of conquest, but as a necessary, even compassionate, measure for the "progress" of both races.

By the early 19th century, the pressure for Native American land intensified dramatically. The burgeoning cotton kingdom in the South demanded ever more acreage for cultivation, while the discovery of gold in Cherokee territory in Georgia in 1828 ignited a feverish rush. The "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole – occupied prime agricultural lands in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida. Ironically, these tribes had, to a significant degree, embraced the very "civilization" Jefferson had advocated. They had adopted written languages (the Cherokee Syllabary, invented by Sequoyah, was a remarkable achievement), established constitutional governments, converted to Christianity, and engaged in farming and even slaveholding, mirroring their white neighbors. The Cherokee Nation, in particular, was a sophisticated, self-governing entity, publishing its own newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix, in both Cherokee and English.

Yet, their assimilation did not protect them. Instead, it fueled the resentment of land-hungry white settlers and politicians who viewed their organized resistance to removal as an affront. The state of Georgia, a hotbed of anti-Indian sentiment, became particularly aggressive, passing laws that nullified Cherokee laws, seized their lands, and made it illegal for them to testify in court against whites. These actions, flagrantly disregarding federal treaties, set the stage for a constitutional crisis.

The figure most synonymous with the Indian Removal Act is Andrew Jackson. A hero of the War of 1812 and a seasoned Indian fighter, Jackson harbored a deep-seated belief that Native Americans were savages incapable of self-governance and that their presence within state borders was an impediment to national progress and security. His personal experiences, including his military campaigns against the Creek Nation, hardened his conviction that removal was the only viable solution. Elected president in 1828 on a wave of populist support, Jackson made Indian Removal a cornerstone of his administration. He saw it not as a violation of rights, but as a "benevolent policy" that would protect Native Americans from the corrupting influence of white society and allow them to thrive in the West. This paternalistic rationale masked the raw desire for land and resources that truly drove the policy.

The debate over the Indian Removal Act in Congress was fierce and protracted. Proponents, largely from the South, echoed Jackson’s arguments, emphasizing states’ rights, the necessity of expansion, and the supposed inability of Native Americans to coexist with white society. They dismissed treaties as agreements with "savages" that could be unilaterally abrogated. Opponents, including prominent figures like Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen of New Jersey and Congressman Davy Crockett of Tennessee, argued passionately against the bill on moral, legal, and constitutional grounds. Frelinghuysen delivered a six-hour speech, declaring that the government had a sacred trust to uphold its treaty obligations: "We have, by the blessing of God, attained to a station which, in the march of empire and the scale of national greatness, is unparalleled in the history of nations… And are we now to turn our backs upon a solemn trust and surrender the poor remnants of this people to destruction?" Davy Crockett, defying his constituents, famously stated, "I would rather be beaten and return to the cane brake and bear’s hunting than stay here and vote against my conscience."

Despite these eloquent appeals, the Act narrowly passed both houses of Congress in May 1830. President Jackson swiftly signed it into law. The Act authorized the President to negotiate with Native American tribes for their removal to federal territory west of the Mississippi River in exchange for their ancestral homelands. Crucially, it did not explicitly mandate removal, but it provided the executive branch with the power and funding to coerce it, often through illegitimate treaties signed by minority factions of tribes.

The Cherokee Nation, led by its principal chief John Ross, refused to yield. They pursued a strategy of legal resistance, appealing to the Supreme Court. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Cherokee Nation was not a foreign state but a "domestic dependent nation," lacking the standing to sue in federal court. However, Marshall’s subsequent ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) was a resounding victory for the Cherokee. The Court declared that Georgia’s laws had no jurisdiction over Cherokee lands and that the Cherokee Nation was a distinct political community with territorial boundaries recognized by federal treaties.

President Jackson, however, infamously defied the Supreme Court. The apocryphal quote, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it," perfectly encapsulates Jackson’s contempt for judicial authority when it clashed with his executive agenda. With the federal government refusing to intervene and protect their rights, and Georgia continuing its aggressive incursions, the Cherokee were left vulnerable.

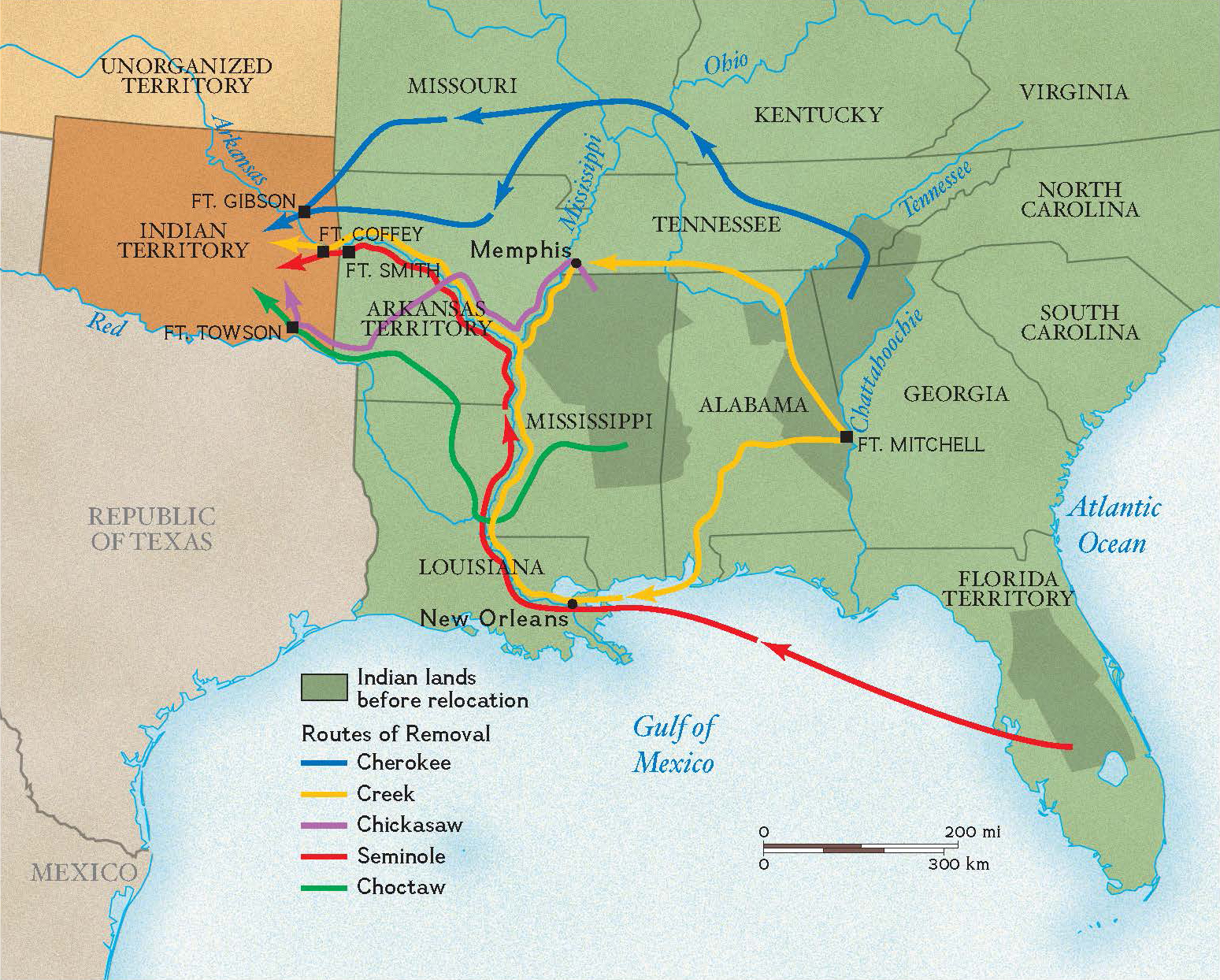

The stage was set for the tragic implementation of the Act. The Choctaw were the first to be forcibly removed in 1831-1833, enduring a brutal winter march with inadequate supplies, leading to widespread suffering and death. This was followed by the Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole. The Seminole in Florida fought back in a protracted and costly series of conflicts known as the Seminole Wars, demonstrating fierce resistance to removal.

For the Cherokee, the end came through deception and internal division. In 1835, a small faction of the Cherokee, known as the "Treaty Party," led by Elias Boudinot and Major Ridge, signed the Treaty of New Echota without the consent of the vast majority of the Cherokee Nation. This treaty ceded all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi in exchange for $5 million and land in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Despite protests from John Ross and over 15,000 Cherokees who signed a petition against it, the U.S. Senate ratified the fraudulent treaty.

In 1838, under President Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s successor, the U.S. Army, led by General Winfield Scott, began the forced removal of the Cherokee. Approximately 16,000 Cherokees were rounded up at bayonet point, often with little more than the clothes on their backs, and held in internment camps. Then began the infamous "Trail of Tears." Marched over 1,200 miles through harsh conditions, without adequate food, water, or shelter, an estimated 4,000 Cherokee men, women, and children perished from disease, starvation, and exposure. An eyewitness, Dr. Elizur Butler, noted, "The Cherokees are nearly all prisoners. They have been dragged from their houses… and left to be plundered by a lawless rabble. It is a scene of horror that I hope I may never witness again."

The Indian Removal Act and its brutal execution represent one of the darkest chapters in American history. It not only dispossessed Native American tribes of their ancestral lands but also shattered their communities, cultures, and self-governance. The policy was predicated on a fundamental denial of Indigenous sovereignty and humanity, driven by a relentless pursuit of land and resources. The legacy of removal continues to reverberate today, impacting the health, wealth, and cultural vitality of Native American communities.

While the Act itself was repealed in 1871 as the federal government shifted to an allotment policy, its impact was irreversible. The forced migrations cemented a pattern of federal control over Native American affairs and set the stage for further injustices. The Trail of Tears, in particular, remains a potent symbol of American broken promises and the human cost of expansion. Understanding the history of the Indian Removal Act is not just about recounting past events; it is about confronting the complexities of American identity, recognizing the resilience of Indigenous peoples, and learning from a period when the nation’s ideals of liberty and justice were tragically denied to an entire population. It stands as a stark reminder that progress, when achieved through the subjugation of others, leaves an indelible stain on the conscience of a nation.