Echoes in the Classroom: Historical Trauma and Cultural Genocide in Education

Education, often hailed as the great equalizer and a pathway to progress, stands at a critical juncture. For countless communities globally, education has been, and in many ways continues to be, a crucible where the searing legacies of historical trauma and cultural genocide manifest, shaping the experiences of students, educators, and the very fabric of learning environments. This is not a distant historical footnote but a living, breathing challenge demanding urgent and profound systemic transformation.

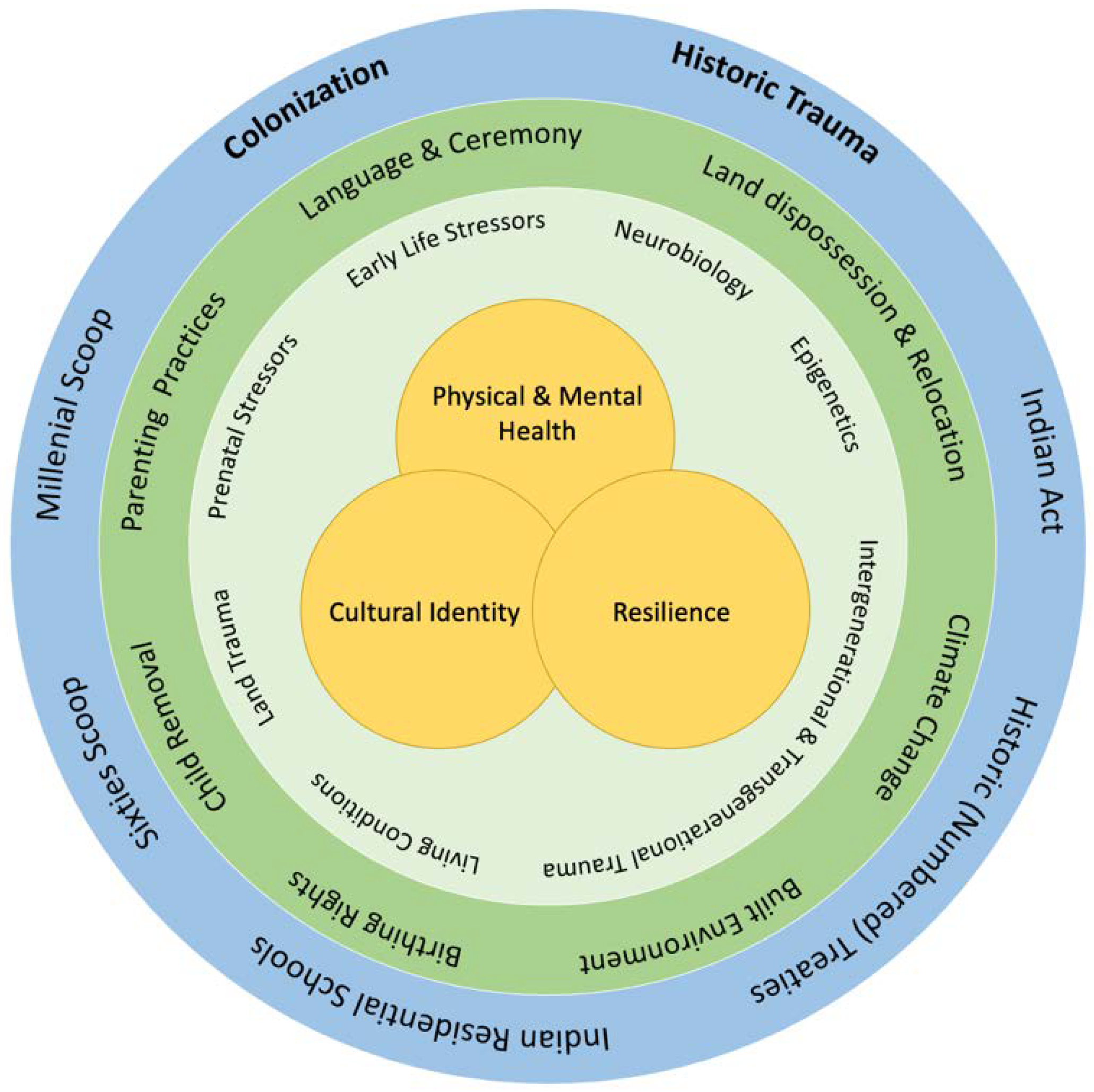

The concept of historical trauma, as articulated by Native American scholar Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, refers to the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experiences. These experiences are often characterized by events that shatter a people’s culture, identity, and spirit, such as colonization, genocide, slavery, forced displacement, and systematic oppression. The Holocaust, the transatlantic slave trade, the Armenian Genocide, and the genocides perpetrated against Indigenous peoples worldwide are stark examples. Unlike individual trauma, historical trauma is collective, intergenerational, and often met with a lack of acknowledgement or resolution from the perpetrating society.

Cultural genocide, a term coined by Raphael Lemkin, the architect of the Genocide Convention, describes the systematic destruction of a group’s culture, language, spiritual practices, social structures, and intellectual heritage. While not involving the direct physical extermination of a people, its intent is to erase their distinct identity, effectively annihilating them as a cultural entity. The infamous "Kill the Indian, Save the Man" policy underlying North American residential schools, the "Stolen Generations" in Australia, and the suppression of African languages and spiritual practices under slavery are prime examples where education was deliberately weaponized as a tool of cultural destruction.

Education as a Weapon: A Historical Reckoning

For centuries, formal education systems have often been complicit, if not direct agents, in the perpetration of cultural genocide. Indigenous residential schools across Canada and the United States, and similar boarding schools globally, serve as the most chilling testament to this. Children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their native languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or express their cultural identities. They were subjected to harsh discipline, physical and sexual abuse, and taught that their heritage was inferior, savage, or evil. The stated goal was assimilation, but the outcome was profound, lasting trauma that severed familial bonds, dismantled communities, and systematically eroded cultural knowledge.

The effects of this state-sponsored cultural violence did not end with the closure of these institutions. They ripple through generations, manifesting as what Brave Heart describes as "unresolved grief." Descendants of survivors often exhibit higher rates of substance abuse, depression, anxiety, PTSD, intergenerational violence, and suicide. They may struggle with identity formation, a deep mistrust of institutions, and difficulty connecting with their own cultural heritage, which was systematically denied to their ancestors. These are not mere social problems; they are symptoms of deep-seated, collective wounds that continue to fester.

The Classroom Today: Manifestations of Unseen Wounds

Today’s classrooms are not immune to these historical echoes. Students from historically traumatized communities often enter school with a complex array of challenges that are often misunderstood or misdiagnosed. These challenges include:

- Learning and Behavioral Difficulties: Chronic stress, anxiety, and a fragmented sense of self can impede concentration, memory, and executive function. What might appear as defiance or disengagement can often be a trauma response—a child struggling to feel safe, regulate emotions, or process information in an environment that may inadvertently trigger historical anxieties.

- Identity Crises: Students may grapple with a fractured sense of identity, caught between the dominant culture and a diminished, often stigmatized, ancestral heritage. They might internalize negative stereotypes, leading to low self-esteem and a lack of belonging.

- Distrust of Institutions: Given the historical role of educational institutions in cultural destruction, students and their families may harbor a deep-seated, justifiable mistrust of schools, teachers, and administrators. This can lead to disengagement, lack of parental involvement, and a perpetuation of educational disparities.

- Mental Health Disparities: The intergenerational transmission of trauma contributes significantly to higher rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions within these communities. Schools, often ill-equipped to address such profound needs, can inadvertently exacerbate these issues.

Beyond individual student experiences, the curriculum itself can perpetuate elements of cultural genocide through omission, misrepresentation, or outright erasure. History textbooks frequently sanitize colonial narratives, minimize the brutality of slavery, or ignore the rich histories and contributions of marginalized groups. This "single story," as author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie eloquently warns, "creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story the only story." When students of color or Indigenous students do not see their histories, cultures, and identities accurately reflected or valued in the curriculum, it reinforces the message that their experiences are irrelevant or inferior, perpetuating a subtle form of cultural invalidation.

Towards Healing: Education as a Tool for Reconciliation

Transforming education from a site of historical trauma to a space of healing and reconciliation requires a multi-faceted approach, one that acknowledges the past, addresses the present, and builds a more equitable future.

-

Trauma-Informed Pedagogy: This approach recognizes the pervasive impact of trauma and emphasizes physical and emotional safety, trustworthiness, peer support, collaboration, empowerment, and cultural sensitivity. Educators trained in trauma-informed practices understand that challenging behaviors are often symptoms of underlying trauma and respond with empathy, patience, and strategies that build resilience rather than merely punishing symptoms. This includes creating predictable routines, fostering strong student-teacher relationships, and providing opportunities for students to regulate their emotions.

-

Culturally Responsive Teaching: Coined by Gloria Ladson-Billings, culturally responsive teaching is a pedagogy that recognizes the importance of including students’ cultural references in all aspects of learning. It involves:

- Validating Students’ Cultures: Actively incorporating students’ languages, traditions, and ways of knowing into the classroom.

- Building on Prior Knowledge: Connecting new learning to students’ lived experiences and cultural backgrounds.

- Challenging the Dominant Narrative: Critically examining curriculum for biases and actively seeking out diverse perspectives.

- Fostering Critical Consciousness: Empowering students to analyze societal inequalities and advocate for justice.

-

Curriculum Reform and Decolonization: This is perhaps the most crucial step. It necessitates a thorough overhaul of educational content to include accurate, comprehensive, and nuanced histories of all peoples. This means:

- Centering Indigenous Voices: Incorporating Indigenous knowledge systems, languages, and perspectives into all subject areas, not just history.

- Acknowledging Injustices: Teaching the unvarnished truths of colonization, slavery, and other historical traumas, including their ongoing impacts.

- Celebrating Diversity: Showcasing the rich cultural contributions of all groups, moving beyond tokenistic representation.

- Language Revitalization: Supporting programs that teach and preserve endangered Indigenous languages, recognizing language as a core component of cultural identity. For example, the success of Māori language immersion schools (Kura Kaupapa Māori) in New Zealand demonstrates the profound impact of linguistic and cultural revitalization on student outcomes and well-being.

-

Educator Training and Professional Development: Teachers must be equipped with the knowledge and skills to address historical trauma and cultural genocide effectively. This includes training on cultural competency, anti-racism, implicit bias, and the specific historical contexts and intergenerational impacts relevant to their student populations. It also involves supporting educators in processing their own biases and discomfort when confronting difficult histories.

-

Community Engagement and Partnership: Schools cannot undertake this work in isolation. Genuine partnerships with families, Elders, community leaders, and cultural organizations are essential. This ensures that educational efforts are respectful, relevant, and rooted in the wisdom and needs of the communities they serve. Programs that invite Elders into classrooms to share stories and knowledge, or that involve community members in curriculum development, can be incredibly powerful.

Conclusion

The echoes of historical trauma and cultural genocide resonate deeply within the walls of our educational institutions. To ignore them is to perpetuate the very harms of the past, denying countless students their right to a full, affirming, and healing educational experience. Education has a profound moral imperative to confront its complicity, acknowledge the wounds, and actively participate in the journey of reconciliation and healing.

This is not merely about adding new chapters to history books; it is about fundamentally rethinking how we teach, what we value, and who we uplift. By embracing trauma-informed and culturally responsive pedagogies, decolonizing curricula, and fostering genuine partnerships with communities, education can transform from a site of historical pain into a powerful catalyst for justice, understanding, and collective well-being. Only by confronting these echoes head-on can education truly become the beacon of equity, understanding, and healing it purports to be, fostering generations that are not only knowledgeable but also whole.