A Silent Crisis: The Plight of Healthcare on Rural Native American Reservations

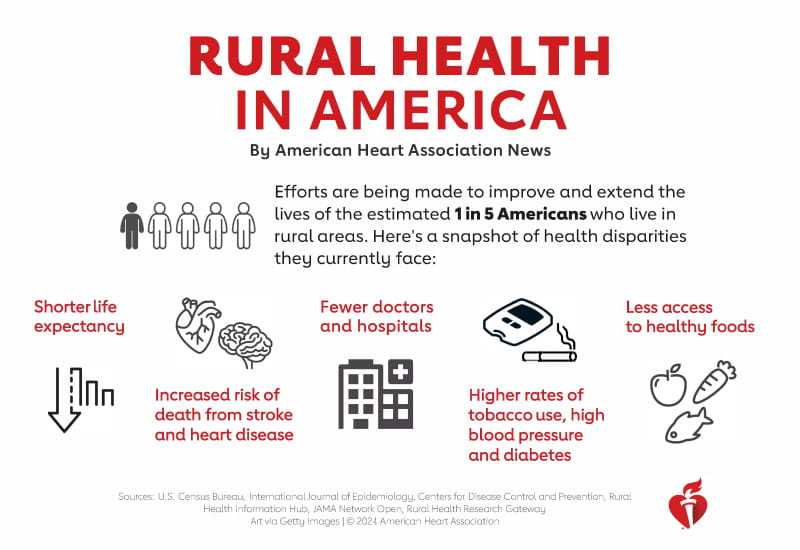

In the vast, often breathtaking landscapes of rural America, where ancient traditions meet modern challenges, a profound and largely unseen healthcare crisis is unfolding. For the nearly 3 million Native Americans living in the United States, particularly those residing on federally recognized reservations, access to adequate healthcare is not a given right, but a daily struggle. This is a story of systemic neglect, historical injustice, and geographic isolation, culminating in some of the most alarming health disparities in the nation.

The statistics paint a grim picture. Native Americans on average have a life expectancy that is 5.5 years shorter than the U.S. general population. They face disproportionately higher rates of chronic diseases, including diabetes (2-3 times higher), heart disease, and cancer. Infant mortality rates are 60% higher, and death rates from unintentional injuries and suicide are 1.5 to 3.5 times higher. These are not mere numbers; they represent generations of families grappling with preventable suffering and premature loss, a testament to a healthcare system that has, for too long, fallen tragically short of its obligations.

The Unfulfilled Promise: A Legacy of Neglect

At the heart of this crisis lies the Indian Health Service (IHS), an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, tasked with providing healthcare to American Indians and Alaska Natives. Its mandate stems from treaties signed centuries ago, wherein tribes ceded vast territories in exchange for services, including healthcare. This is not charity; it is a solemn trust responsibility of the U.S. government. Yet, the IHS has been chronically and severely underfunded for decades, operating at a fraction of what other federal healthcare systems receive.

"The IHS budget is a national embarrassment," states Dr. Sarah Jones, a public health advocate who has worked on reservations for over two decades. "While the VA spends over $15,000 per veteran annually and federal prisoners receive about $11,000 in healthcare, the IHS struggles with roughly $4,000 per person. How can we expect to deliver equitable care with such a stark disparity in resources?" This funding gap translates directly into critical shortages of doctors, nurses, and specialists, crumbling infrastructure, outdated equipment, and an inability to provide the full spectrum of necessary medical services.

Geographic Isolation and Infrastructural Barriers

Many reservations are located in remote, rural areas, often hundreds of miles from the nearest urban centers. This geographic isolation is a formidable barrier to care. Paved roads can be scarce, and public transportation non-existent. For a patient suffering from a chronic condition, a simple doctor’s visit can mean an all-day journey, costing precious time and resources.

"I had to drive my grandmother three hours one way for a dialysis appointment," recounts Maria Yazzie, a Navajo Nation member. "She was in pain, and we had to leave before dawn. There’s no specialist closer. Many times, people just don’t go because they can’t afford the gas or the time off work." This anecdote highlights a pervasive issue: even when services are available, the logistics of accessing them are often insurmountable.

Beyond transportation, basic infrastructure is often lacking. Many homes on reservations still lack clean running water and adequate sanitation, leading to higher rates of infectious diseases. Food deserts are common, with limited access to fresh, nutritious produce, contributing to diet-related illnesses like diabetes and heart disease. Broadband internet, a crucial tool for telemedicine in remote areas, remains a luxury for many. This web of interconnected deprivations exacerbates health challenges and undermines efforts to improve well-being.

A System Stretched Thin: The IHS on the Ground

The consequences of underfunding are acutely felt within IHS facilities. Clinics are often old and poorly maintained. Staff turnover is high, as medical professionals are drawn to better-resourced facilities with competitive salaries and less demanding workloads. This means fewer doctors, longer wait times, and a limited scope of services. Specialty care—like cardiology, oncology, or mental health services—is particularly scarce. Patients often require referrals to off-reservation providers, a process fraught with bureaucratic hurdles and further financial strain.

Mental health and substance abuse are critical concerns, magnified by historical trauma and socioeconomic stressors. Native American youth face suicide rates significantly higher than the national average. Opioid addiction and alcoholism continue to devastate communities. Yet, mental health professionals are in critically short supply within the IHS system, and culturally appropriate treatment options are even rarer. "We need more than just therapy; we need healing that acknowledges our history, our culture, our spirituality," says a tribal elder. "That’s hard to find in a system designed for a different world."

The Human Toll: Specific Health Crises

The healthcare disparities translate into distinct and devastating health crises:

- Diabetes Epidemic: Type 2 diabetes is rampant, often striking younger individuals. This is linked to genetic predispositions, but also heavily influenced by forced dietary changes, poverty, and limited access to healthy foods. Complications like kidney failure, blindness, and amputations are tragically common.

- Maternal Mortality: Native American women face maternal mortality rates that are 2-3 times higher than white women. Factors include limited access to prenatal care, high-risk pregnancies due to chronic conditions, and systemic biases within the healthcare system. The journey to a safe birthing facility can be arduous, further endangering mothers and infants.

- Environmental Health: Many reservations are located near former mining sites or industrial operations, leaving a legacy of environmental contamination. Exposure to uranium, arsenic, and other toxins contributes to higher rates of cancer, respiratory illnesses, and birth defects, adding another layer of complexity to their health struggles.

Cultural Competency and Traditional Healing

Beyond the structural and financial issues, there is often a profound disconnect between Western medical practices and Native American cultural values and healing traditions. Mainstream healthcare providers may lack understanding of tribal customs, spiritual beliefs, and the concept of holistic health that integrates mind, body, and spirit. This can lead to miscommunication, distrust, and a reluctance to seek care.

However, there is a growing movement within tribal communities to integrate traditional healing practices with Western medicine. Many tribes are establishing their own health departments, often operating under "638" contracts with the IHS, allowing them greater control over funding and service delivery. These tribal-led initiatives prioritize cultural competency, employ community health workers who understand local nuances, and sometimes incorporate traditional healers and ceremonies into care plans. This self-determination is seen as crucial for developing healthcare models that are truly responsive to community needs.

Glimmers of Hope and the Path Forward

Despite the daunting challenges, there are beacons of hope. Telemedicine, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, has shown immense potential in bridging geographic gaps, offering remote consultations and specialty care. Tribal nations are increasingly asserting their sovereignty, taking control of their health systems, and advocating fiercely for increased and stable funding from the federal government. Grassroots organizations and Native-led non-profits are working tirelessly to address food insecurity, provide transportation, and promote health education.

"We are resilient people," states a tribal council member. "We have faced immense adversity, and we continue to fight for the health and well-being of our communities. What we need is for the federal government to uphold its end of the bargain, to invest in our health with the same commitment they show to other populations. It’s not just about money; it’s about justice, equity, and honoring treaties."

The healthcare crisis on rural Native American reservations is a stark reminder of historical injustices and ongoing systemic inequalities. Addressing it requires more than just increased funding, though that is a crucial first step. It demands a holistic approach that respects tribal sovereignty, invests in infrastructure, promotes cultural competency, and acknowledges the deep-seated trauma that continues to impact Native communities. Only then can the promise of health equity truly begin to take root in these remote lands, allowing Native Americans to thrive and reclaim their inherent right to well-being. The time for a silent crisis to become a public priority is long overdue.