Echoes of the Wind: The Enduring Legacy of the Great Plains Native American Tribes

The vast expanse of the North American Great Plains, a landscape of sweeping grasslands and endless skies, has for millennia been home to a tapestry of indigenous nations whose histories are as rich and complex as the land itself. From the semi-nomadic farmers of the eastern plains to the horse-mounted buffalo hunters of the west, these tribes developed distinct cultures, spiritual beliefs, and social structures, all profoundly shaped by their environment and an intricate relationship with its most iconic inhabitant: the American bison. Their story is one of profound adaptation, spiritual depth, fierce independence, and ultimately, an enduring resilience in the face of cataclysmic change.

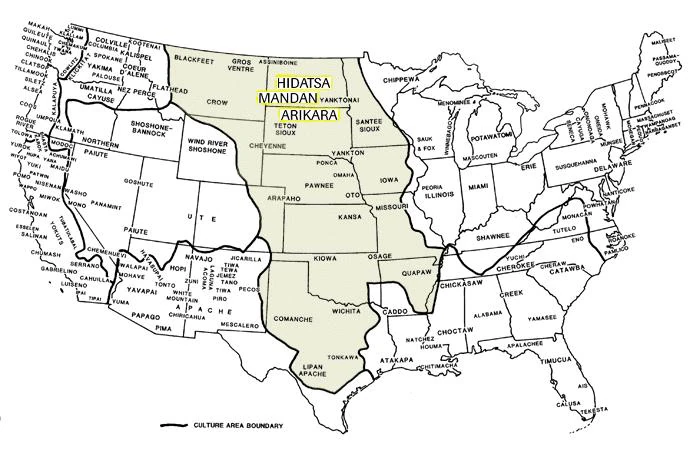

Before the arrival of Europeans and the transformative introduction of the horse, life on the Plains was diverse. Eastern Plains tribes like the Pawnee, Omaha, and Osage were semi-sedentary, cultivating corn, beans, and squash along river valleys while also undertaking seasonal bison hunts. Their villages consisted of earth lodges – sturdy, dome-shaped structures that offered protection from the harsh elements. Further west, groups like the proto-Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho were more foot-mobile, relying heavily on communal bison hunts, using dogs to pull travois laden with their belongings as they followed the herds. Their lives were dictated by the rhythm of the seasons and the migratory patterns of the buffalo, a creature whose very existence defined their own.

The horse, introduced by the Spanish in the 16th century, irrevocably altered the destiny of the Plains tribes. What began as a trickle of stray animals soon became a flood, as tribes acquired and bred horses, becoming master equestrians. The horse was not merely a tool; it was a revolution. It transformed hunting, allowing tribes to pursue bison with unprecedented efficiency and speed, dramatically increasing food security and wealth. It reshaped warfare, making raids more swift and effective, and it expanded tribal territories and trade networks. The tipi, a conical dwelling of tanned hides, became the perfect portable home for these newly mobile societies, easily erected and dismantled, perfectly suited to a nomadic lifestyle that followed the herds.

With the horse came an explosion of cultural innovation and distinct identities. Tribes like the Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Crow, Blackfoot, and Kiowa emerged as dominant forces. Their societies were often organized into bands, governed by councils of respected elders and warrior chiefs. Warrior societies, such as the Dog Soldiers of the Cheyenne or the Kit Foxes of the Lakota, played a crucial role in defense, hunting, and maintaining social order, with prestige earned through acts of bravery, known as "counting coup." These acts might involve touching an enemy in battle without killing them, a profound demonstration of courage.

Central to all Plains cultures was a deep spiritual connection to the land and its creatures. The bison, or buffalo, was not just food; it was a sacred relative, a gift from the Creator. "Every part of the buffalo was used," goes the common saying, and it’s a profound understatement. Its meat provided sustenance, hides became tipis, clothing, and robes, bones were crafted into tools, sinews into thread, and even dung was used as fuel. This holistic relationship fostered a worldview of interconnectedness and respect for the natural world. Ceremonies like the Sun Dance, a powerful rite of renewal, sacrifice, and community bonding, reinforced these spiritual ties, seeking blessings for the people and the earth. Vision quests, undertaken by individuals seeking guidance and spiritual power, connected them directly to the unseen forces of the universe. Storytelling, often passed down through oral tradition, preserved histories, moral lessons, and sacred narratives, ensuring that wisdom was transmitted across generations.

However, this vibrant way of life was increasingly threatened by the relentless tide of American westward expansion. Initial encounters with European Americans brought trade goods like metal tools, firearms, and blankets, but also devastating diseases like smallpox, against which Native peoples had no immunity. As the 19th century progressed, the trickle of explorers and traders turned into a flood of settlers, miners, and railroad builders, all encroaching upon tribal lands.

The U.S. government’s policy shifted from treaties of co-existence to demands for land cession and, eventually, to forced removal and assimilation. Treaties, often signed under duress or misunderstood, were routinely violated by settlers and the government alike. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills, sacred lands to the Lakota, ignited renewed conflict. The Plains Indian Wars, a series of brutal conflicts throughout the latter half of the 19th century, pitted the technologically superior U.S. Army against the determined resistance of tribal warriors. Iconic figures like Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, and Geronimo (though primarily Apache, his resistance resonated across the West) emerged as symbols of defiance.

The Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, where a coalition of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors decisively defeated General George Custer’s 7th Cavalry, was a stunning, albeit temporary, victory for the tribes. It was also a moment that galvanized the American public and military into even more aggressive action. The systematic slaughter of the bison, orchestrated by the U.S. government and hide hunters, was perhaps the most devastating blow, aimed at stripping the Plains tribes of their primary resource and forcing them onto reservations. From millions, the herds dwindled to mere hundreds, tearing the heart out of Plains culture.

The final act of resistance and tragedy unfolded at Wounded Knee in December 1890, where hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were massacred by the U.S. Army. This event marked the symbolic end of the Indian Wars and the forced subjugation of the Plains tribes. Confined to reservations, often on marginal lands, and subjected to policies designed to eradicate their culture – children sent to boarding schools, languages forbidden, spiritual practices suppressed – the Plains peoples faced an existential crisis. As Sitting Bull famously stated, "Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children." This enduring spirit of looking to the future, even in the darkest times, is a testament to their strength.

Yet, despite these immense challenges, the spirit of the Great Plains Native American tribes has never been extinguished. Their story is not one of disappearance, but of profound resilience and adaptation. In the 20th and 21st centuries, tribes have actively worked to reclaim their sovereignty, revitalize their languages, and preserve their cultural heritage. Tribal colleges offer education rooted in indigenous values, language immersion programs are bringing back ancestral tongues, and traditional ceremonies are once again openly practiced, fostering a renewed sense of identity and community. Economic development, often through casinos, tourism, or resource management, provides new avenues for self-sufficiency, though poverty and its associated social issues remain significant challenges on many reservations.

The wisdom of the Plains peoples – their deep understanding of ecological balance, their community-oriented values, their spiritual reverence for nature – offers invaluable lessons for the modern world. Their history serves as a powerful reminder of the consequences of conquest and the importance of respecting diverse cultures and the land that sustains us all.

Today, the descendants of the Great Plains tribes continue to live on their ancestral lands, honoring the sacrifices of their forebears and building vibrant futures. The echoes of the wind still carry the stories of the buffalo, the thunder of horses, and the enduring spirit of a people who, despite every effort to erase them, remain an integral and vital part of the American landscape and cultural mosaic. Their journey is a testament to the strength of the human spirit, forever bound to the vast, open heart of the Plains.