The Golden Scourge: How America’s Gold Rushes Fueled Native American Displacement

The word "gold rush" conjures images of rugged prospectors, dusty boomtowns, and the thrilling pursuit of fortune. It’s a quintessential American narrative, romanticized in countless tales of ambition and discovery. Yet, beneath this glittering facade lies a darker, often overlooked truth: the gold rushes were, for Native American communities, an unmitigated catastrophe, accelerating a brutal campaign of displacement, violence, and cultural destruction that irrevocably altered the landscape and its original inhabitants. These sudden influxes of fortune-seekers, driven by avarice and often sanctioned by a government bent on territorial expansion, systematically dismantled established Indigenous societies and seized ancestral lands, leaving a legacy of trauma that endures to this day.

The story of gold and its devastating impact on Native Americans is not a singular event but a recurring pattern across the continent, from the earliest discoveries in the southeastern United States to the famed California and Black Hills rushes, and even to the remote reaches of the Klondike. Each discovery ignited a frenzy, drawing a tidal wave of prospectors, opportunists, and accompanying military forces into Native territories, shattering fragile treaties and traditional ways of life.

California: A Genocide Masked by Gold

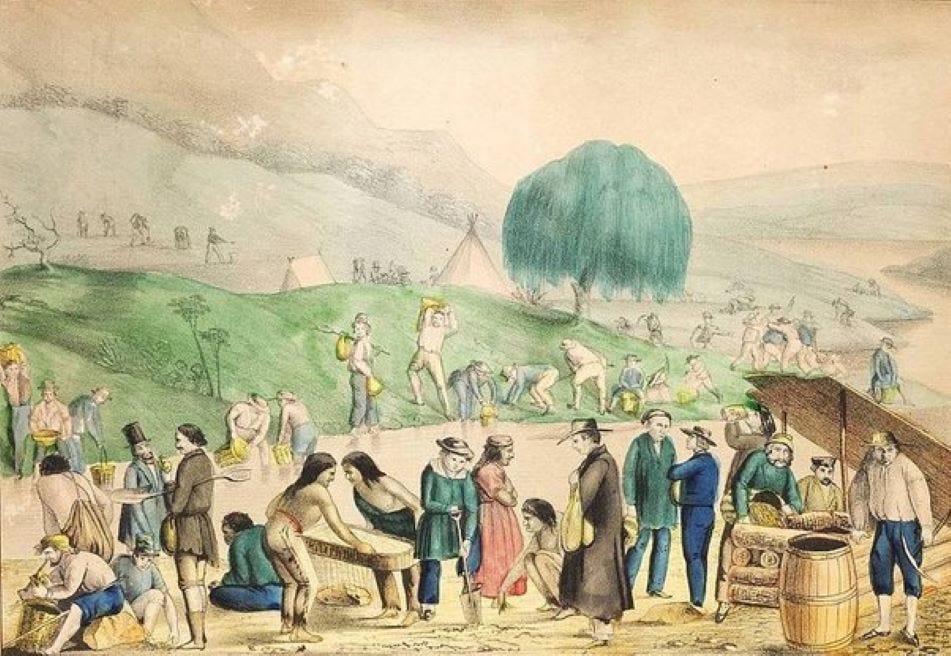

Perhaps the most infamous and brutal example unfolded in California. The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848 transformed the sleepy Mexican territory, recently annexed by the United States, into a global magnet. Within two years, California’s population exploded from approximately 15,000 non-Native residents to over 100,000, and by 1852, it had swelled to over a quarter-million. This massive, sudden demographic shift was catastrophic for the state’s diverse Indigenous population.

Prior to the gold rush, California’s Native population was estimated to be around 150,000. By 1870, this number had plummeted to roughly 30,000. This staggering 80% decline was not merely a consequence of disease, though epidemics certainly played a role. It was the result of a deliberate, state-sanctioned campaign of extermination. Miners, often organized into vigilante militias, attacked Native villages, massacring men, women, and children with impunity. The state government actively funded these militias, reimbursing them for their expenditures in "Indian campaigns" and even providing bounties for Native American scalps and body parts.

As historian Benjamin Madley details in his book, "An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873," these acts were not random violence but a systematic effort to eliminate Native people from lands desired by miners and settlers. The state’s 1850 "Act for the Government and Protection of Indians," ostensibly designed to protect Indigenous people, instead legalized their forced labor, effectively turning them into indentured servants, and allowed for the removal of Native children from their families. This legislative framework, combined with rampant violence, starvation, and disease, created a genocidal environment.

The destruction extended beyond human lives. Traditional hunting grounds were decimated by mining operations, which fouled rivers with silt and mercury, destroyed forests for timber, and drove away game. Salmon runs, a staple for many tribes, were obliterated. The very ecosystems that had sustained Indigenous communities for millennia were irrevocably altered, severing their connection to the land and their ability to practice their traditional livelihoods.

The Black Hills: A Sacred Trust Betrayed

Further east, in the Dakota Territory, another gold rush ignited a conflict that became legendary: the Black Hills Gold Rush. The Black Hills (Paha Sapa) were, and remain, sacred lands for the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota Sioux, central to their spiritual beliefs and cultural identity. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, signed by the U.S. government and several Sioux bands, explicitly guaranteed the Lakota "undisturbed use and occupation" of the Great Sioux Reservation, which included the Black Hills, "as long as the grass shall grow and the water flow."

However, this solemn pledge proved to be as fragile as the paper it was written on. In 1874, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition into the Black Hills, ostensibly to survey the land. His true mission, however, was to confirm rumors of gold. Custer’s reports of "gold from the grass roots down" sent shockwaves across the nation, triggering an immediate and illegal influx of prospectors into the protected Lakota territory.

The U.S. government, rather than upholding its treaty obligations and expelling the trespassers, attempted to purchase the Black Hills from the Lakota. When the Sioux chiefs, including Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, vehemently refused to sell their sacred lands, the government issued an ultimatum: return to the agencies by January 31, 1876, or be deemed hostile. This set the stage for the Great Sioux War of 1876-77, a conflict that included the Battle of Little Bighorn, where Custer and his command were famously annihilated.

Despite the Lakota’s fierce resistance, the superior military force and relentless pressure of the United States ultimately prevailed. In 1877, Congress unilaterally passed an act seizing the Black Hills, effectively nullifying the 1868 treaty. The Lakota were forced onto smaller, scattered reservations, their sacred lands parceled out to miners and settlers. The betrayal of the Black Hills remains a potent symbol of broken promises and the government’s willingness to sacrifice Indigenous rights for economic gain.

Beyond California and the Black Hills: A Pattern of Predation

The narrative of gold rushes fueling displacement wasn’t confined to these two prominent examples. In Georgia in the 1820s, the discovery of gold on Cherokee lands intensified the pressure for their removal, culminating in the forced migration known as the Trail of Tears. Even in the Klondike Gold Rush of the late 1890s, while not directly involving the U.S. military to the same extent, the massive influx of prospectors into the Yukon and Alaska disrupted Indigenous hunting and fishing grounds, brought disease, and imposed foreign economic structures on Native communities, fundamentally altering their way of life.

Common threads connect these disparate events:

- Treaty Violations: Gold discoveries frequently occurred on lands explicitly protected by treaties, which the U.S. government then either ignored, reinterpreted, or unilaterally abrogated.

- Environmental Degradation: Mining operations, particularly hydraulic and placer mining, devastated rivers, forests, and landscapes, destroying traditional food sources and sacred sites.

- Violence and Disease: Prospectors and accompanying settlers brought with them diseases to which Native populations had no immunity, alongside direct violence, often escalating into massacres.

- Forced Removal and Reservations: The ultimate goal was often the physical removal of Native peoples from resource-rich lands and their confinement to reservations, typically on marginal lands unsuitable for traditional subsistence.

- Cultural Disruption: The rapid and overwhelming influx of outsiders shattered social structures, disrupted spiritual practices, and undermined traditional governance systems.

The Enduring Legacy

The gold rushes represent a particularly brutal chapter in the long history of Native American displacement in the United States. They laid bare the true cost of "Manifest Destiny" – the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand westward – revealing it to be a thinly veiled justification for land theft and cultural destruction. The pursuit of wealth, framed as progress and opportunity, came at an unimaginable price for the Indigenous peoples whose ancestral lands were invaded.

The reverberations of these historical injustices are still felt today. Many Native American communities continue to grapple with intergenerational trauma, poverty, and the loss of cultural heritage directly linked to the gold rushes and subsequent land seizures. Legal battles over land rights and treaty obligations, such as the ongoing struggle for the return of the Black Hills, serve as constant reminders that the wounds of the past are far from healed.

The romanticized image of the gold rush, while capturing a spirit of adventure, must be tempered by the stark reality of its impact on Native Americans. It is a history that compels us to confront the complex and often painful origins of national prosperity and to acknowledge the enduring legacy of a golden age built upon a foundation of Indigenous dispossession. Only by understanding this full, unvarnished history can we begin to address its lingering injustices and work towards a more equitable future.