Last Updated: 7 years

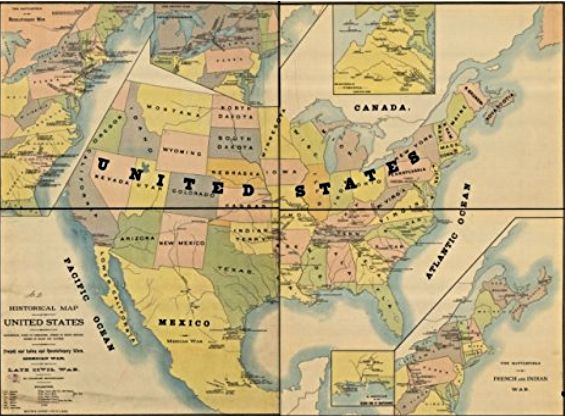

The year is 1754. The vast, untamed wilderness of North America becomes the stage for a burgeoning conflict. British and French forces, long-standing rivals on the European stage, begin to clash over control of the continent’s rich resources and strategic territories. These initial skirmishes mark the beginning of the French and Indian War, a struggle that would dramatically reshape the political landscape of North America.

Two years later, in 1756, the flames of this localized war ignite a far greater conflagration. The conflict spreads across the Atlantic to Europe, where it becomes known as the Seven Years’ War. This expansion transforms the struggle into a global conflict, drawing in major European powers and extending its reach to distant corners of the world.

In many ways, the French and Indian War and its European counterpart can be seen as an extension of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748). The earlier war, a complex tangle of dynastic ambitions and territorial disputes, had left many issues unresolved. The new conflict sees a significant realignment of alliances, with Great Britain forging a partnership with Prussia, while France aligns itself with Austria, reversing their positions from the previous war.

The French and Indian War earns the distinction of being the first truly global war. Battles rage not only across Europe and North America, but also in Africa, India, and even the Pacific Ocean. This global scope reflects the burgeoning colonial empires of the European powers and their intense competition for resources and influence. The war culminates in 1763, leaving France significantly weakened and stripped of the majority of its North American territories.

The Situation in North America

In the British colonies of North America, the conflict’s initial phase was known as King George’s War. This earlier conflict, a theater of the War of Austrian Succession, had seen colonial troops achieve a remarkable feat of arms by capturing the formidable French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island. This victory, however, proved bittersweet. When peace was declared, Louisbourg was returned to France, a decision that sparked resentment and a sense of betrayal among the colonists.

As the French and Indian War approached, the British colonies occupied a substantial portion of the Atlantic coastline. However, they were effectively encircled by French territories to the north and west. France, determined to control this vast expanse stretching from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to the Mississippi Delta, had established a network of outposts and forts. This strategic line ran from the western Great Lakes south to the Gulf of Mexico, effectively containing the expansion of the British colonies.

The French presence left a wide swathe of land between their garrisons and the crest of the Appalachian Mountains. This territory, largely drained by the Ohio River, was claimed by the French. However, it was increasingly attracting British settlers seeking new opportunities beyond the mountains.

The burgeoning population of the British colonies fueled this westward expansion. By 1754, the colonies boasted approximately 1,160,000 white inhabitants, along with an additional 300,000 enslaved Africans. These numbers dwarfed the population of New France, which totaled around 55,000 in present-day Canada and another 25,000 in other areas. This demographic imbalance played a significant role in the escalating tensions between the two European powers.

Caught between these rival empires were the Native American tribes, among whom the Iroquois Confederacy stood as the most powerful. Initially composed of the Mohawk, Seneca, Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga nations, the confederacy later became known as the Six Nations with the addition of the Tuscarora.

The Iroquois Confederacy controlled a vast territory stretching between the French and British settlements, from the upper reaches of the Hudson River west into the Ohio River basin. Officially neutral, the Six Nations were strategically courted by both European powers, skillfully trading with whichever side offered the most advantageous terms. This delicate balancing act allowed them to maintain their independence and influence amidst the escalating conflict.

The French Stake Their Claim

To assert their control over the Ohio Country, the Marquis de La Galissonière, governor of New France, dispatched Captain Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville in 1749 to reaffirm and mark the border.

Céloron de Blainville’s expedition, comprised of approximately 270 men, departed from Montreal and traversed present-day western New York and Pennsylvania. As they progressed, the expedition meticulously placed lead plates at the mouths of various creeks and rivers, proclaiming France’s claim to the land. These plates served as a physical manifestation of French sovereignty and a warning to encroaching British settlers.

Upon reaching Logstown on the Ohio River, Céloron de Blainville evicted several British traders and sternly admonished the Native Americans against trading with anyone but the French. After passing present-day Cincinnati, he turned north and returned to Montreal, having completed his mission of asserting French dominance.

Despite Céloron de Blainville’s expedition, British settlers, particularly those from Virginia, continued to push westward across the Appalachian Mountains. This movement was actively supported by the colonial government of Virginia, which granted land in the Ohio Country to the Ohio Land Company. The company dispatched surveyor Christopher Gist to scout the region and secured permission from the Native Americans to fortify the trading post at Logstown.

The new governor of New France, the Marquis de Duquesne, keenly aware of these increasing British incursions, dispatched Paul Marin de la Malgue to the area with 2,000 men in 1753 to construct a new series of forts.

The first of these forts was built at Presque Isle on Lake Erie (present-day Erie, Pennsylvania), with another constructed twelve miles south at French Creek (Fort Le Boeuf). Pushing further down the Allegheny River, Marin captured the British trading post at Venango and built Fort Machault. These actions alarmed the Iroquois, who lodged complaints with British Indian agent Sir William Johnson.

The British Response

Robert Dinwiddie, the lieutenant governor of Virginia, grew increasingly concerned by Marin’s construction of forts. He lobbied for the construction of a similar chain of British forts, but received permission only on the condition that he first assert British rights to the French. To accomplish this delicate task, he dispatched young Major George Washington on October 31, 1753.

Accompanied by Gist, Washington traveled north, pausing at the strategic Forks of the Ohio, where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers converge to form the Ohio. Reaching Logstown, the party was joined by Tanaghrisson (Half King), a Seneca chief who harbored deep resentment towards the French.

The party ultimately reached Fort Le Boeuf on December 12, where Washington met with Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, the French commander. Presenting an order from Dinwiddie demanding the French to depart, Washington received a firm refusal from Legardeur. Returning to Virginia, Washington reported the situation to Dinwiddie, confirming the French determination to maintain their presence in the Ohio Country.

First Shots Are Fired

Before Washington’s return, Dinwiddie had dispatched a small contingent of men under William Trent to begin constructing a fort at the Forks of the Ohio. Arriving in February 1754, they began building a small stockade, but were forced to abandon their work in April by a French force led by Claude-Pierre Pecaudy de Contrecoeur. The French took possession of the site and began constructing a new, more substantial base, which they named Fort Duquesne.

Upon presenting his report in Williamsburg, Washington received orders to return to the Forks with a larger force to assist Trent in his work. Learning of the French force en route, he pressed on with the support of Tanaghrisson. Arriving at Great Meadows, approximately 35 miles south of Fort Duquesne, Washington halted, recognizing that his force was significantly outnumbered.

Establishing a base camp in the meadows, Washington began exploring the surrounding area while awaiting reinforcements. Three days later, he received word of the approach of a French scouting party.

After assessing the situation, Washington heeded Tanaghrisson’s advice to attack. Washington and approximately 40 of his men marched through the night in harsh weather. They located the French camped in a narrow valley and surrounded their position before opening fire.

In the resulting Battle of Jumonville Glen, Washington’s men killed 10 French soldiers and captured 21, including their commander, Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville. This clash marked the opening shots of the French and Indian War.

After the battle, while Washington was interrogating Jumonville, Tanaghrisson approached and killed the French officer with a tomahawk. This act, the motives for which remain debated, further escalated the conflict.

Anticipating a French counterattack, Washington withdrew to Great Meadows and constructed a crude stockade known as Fort Necessity. Despite receiving reinforcements, his force remained outnumbered when Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers arrived at Great Meadows with 700 men on July 1.

The Battle of Great Meadows began, and Coulon quickly compelled Washington to surrender. Allowed to withdraw with his men, Washington departed the area on July 4, marking an early defeat for the British.

The Albany Congress

While these events unfolded on the frontier, the northern colonies grew increasingly concerned about French activities. Representatives from various British colonies convened in Albany in the summer of 1754 to discuss plans for mutual defense and to renew their agreements with the Iroquois, known as the Covenant Chain.

During the talks, Iroquois representative Chief Hendrick requested the reappointment of Johnson and expressed concern over British and French activities. His concerns were largely addressed, and the Six Nations representatives departed after receiving customary presents.

The representatives also debated a plan for uniting the colonies under a single government for mutual defense and administration. This proposal, known as the Albany Plan of Union, required an Act of Parliament to implement, as well as the support of the colonial legislatures. The brainchild of Benjamin Franklin, the plan received little support among the individual legislatures and was not addressed by Parliament in London, highlighting the challenges of achieving colonial unity.

British Plans for 1755

Though war with France had not been formally declared, the British government, led by the Duke of Newcastle, developed plans for a series of campaigns in 1755 designed to curtail French influence in North America.

Major General Edward Braddock was to lead a large force against Fort Duquesne, while Sir William Johnson was to advance up Lakes George and Champlain to capture Fort St. Frédéric (Crown Point).

In addition to these efforts, Governor William Shirley, elevated to the rank of major general, was tasked with reinforcing Fort Oswego in western New York before moving against Fort Niagara. To the east, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Monckton received orders to capture Fort Beauséjour on the frontier between Nova Scotia and Acadia. These ambitious plans aimed to strike at key French strongholds across the continent.

Braddock’s Failure

Designated the commander-in-chief of British forces in America, Braddock was persuaded by Dinwiddie to launch his expedition against Fort Duquesne from Virginia, as the resulting military road would benefit the lieutenant governor’s business interests.

Assembling a force of around 2,400 men, he established his base at Fort Cumberland, Maryland, before pushing north on May 29. Accompanied by Washington, the army followed his earlier route towards the Forks of the Ohio. Progress was slow as the men cut a road for the wagons and artillery. Braddock sought to increase his speed by rushing forward with a light column of 1,300 men.

Alerted to Braddock’s approach, the French dispatched a mixed force of infantry and Native Americans from Fort Duquesne under the command of Captains Liénard de Beaujeu and Captain Jean-Daniel Dumas. On July 9, 1755, they ambushed the British in the Battle of the Monongahela.

In the ensuing chaos, Braddock was mortally wounded and his army routed. The defeated British column retreated to Great Meadows before falling back towards Philadelphia. The Battle of the Monongahela was a devastating blow to British morale and a testament to the effectiveness of combined French and Native American tactics.

To the east, Monckton achieved success in his operations against Fort Beauséjour. Beginning his offensive on June 3, he positioned his forces to begin shelling the fort ten days later. On July 16, British artillery breached the fort’s walls, and the garrison surrendered.

The capture of the fort was marred later that year when Nova Scotia’s governor, Charles Lawrence, initiated the expulsion of the French-speaking Acadian population from the area, a tragic event known as the Great Expulsion.

In western New York, Shirley moved through the wilderness and arrived at Oswego on August 17. Approximately 150 miles short of his goal, he paused amid reports that French strength was massing at Fort Frontenac across Lake Ontario. Hesitant to push on, he elected to halt for the season and began enlarging and reinforcing Fort Oswego, foregoing his campaign against Fort Niagara.

As the British campaigns progressed, the French benefited from knowledge of the enemy’s plans, having captured Braddock’s letters at Monongahela.

This intelligence led French commander Baron Dieskau to move down Lake Champlain to block Johnson rather than embarking on a campaign against Shirley.

Seeking to attack Johnson’s supply lines, Dieskau moved up (south) Lake George and scouted Fort Lyman (Edward). On September 8, his force clashed with Johnson’s at the Battle of Lake George. Dieskau was wounded and captured in the fighting, and the French were forced to withdraw.

As it was late in the season, Johnson remained at the southern end of Lake George and began construction of Fort William Henry. Moving down the lake, the French retreated to Ticonderoga Point on Lake Champlain, where they completed construction of Fort Carillon. With these movements, campaigning in 1755 effectively ended.

What began as a frontier war in 1754, would soon explode into a global conflict.