Fort Sill Apache Tribal History: From Prisoners of War to Sovereign Nation

The narrative of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe is unlike any other in American history – a testament to endurance, cultural resilience, and the relentless pursuit of self-determination. For over a quarter-century, they bore the official designation of "prisoners of war" by the United States government, a unique and harrowing chapter that began with the surrender of Geronimo and his band in 1886. From the humid confines of Florida prisons to the windswept plains of Oklahoma, these Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apache people navigated an existential struggle, ultimately emerging not just as survivors, but as a vibrant, sovereign nation. Their journey from captivity to self-governance is a profound chronicle of adaptation, resistance, and the enduring spirit of a people determined to reclaim their destiny.

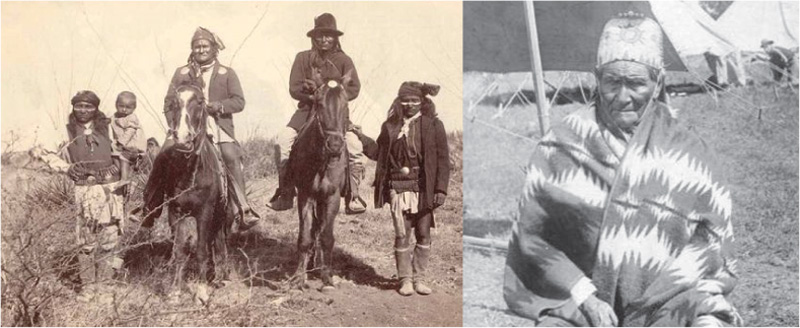

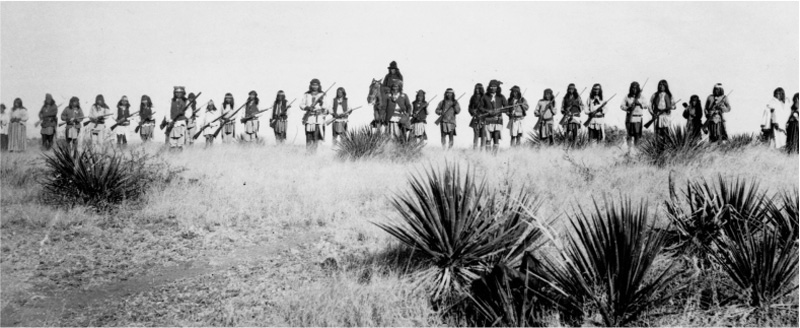

The story begins in the arid landscapes of Arizona and New Mexico, the ancestral lands of the Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apache. For decades, these Apache bands, led by formidable figures like Cochise, Victorio, Nana, and later Geronimo, fiercely resisted the encroachment of American and Mexican settlers. Their campaigns, often brutal and protracted, were a desperate fight for their homeland and way of life. The final, dramatic chapter of these "Apache Wars" culminated in 1886, with the relentless pursuit of Geronimo and his small band by General Nelson Miles. Exhausted and outnumbered, Geronimo’s surrender in Skeleton Canyon, Arizona, marked not just the end of an era of resistance but the beginning of an unprecedented period of captivity for his people.

Following the surrender, the U.S. government made a decision that would define the next 27 years of Apache history: they designated Geronimo and his followers, including women and children, as prisoners of war. This was not merely a symbolic label; it dictated their lives, their movements, and their very existence. The initial destination was Fort Pickens in Florida, a coastal fortress ill-suited for people accustomed to the mountains and deserts. The change in climate, diet, and environment was devastating. Many succumbed to tuberculosis and other diseases, their bodies unaccustomed to the damp heat and unfamiliar pathogens. The psychological toll was immense, as families were sometimes separated, and their traditional ways of life were abruptly suppressed.

From Fort Pickens, the Apache prisoners were moved to Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama. Conditions improved slightly, with more land for gardening and some attempts at vocational training, but they remained under strict military guard. The government’s intent was clear: to "civilize" and assimilate the Apache, erasing their warrior culture and traditional identity. Children were often sent to Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, a notorious institution designed to strip Native American children of their heritage through forced English language instruction, religious conversion, and vocational training. While some Apache children gained valuable skills and an understanding of the dominant culture, many suffered profound trauma and cultural dislocation. The older generations, meanwhile, clung tenaciously to their language, stories, and spiritual practices, nurturing the embers of their heritage in secret.

The turning point in their captivity came in 1894 when the Apache prisoners were relocated yet again, this time to Fort Sill in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This move, advocated by concerned citizens and some military officials who recognized the dire conditions in the South, offered a glimmer of hope. At Fort Sill, they were given significantly more land – approximately 27,000 acres – to farm and raise cattle. While still prisoners of war under military jurisdiction, this new environment allowed for a semblance of community life to re-emerge. They established what became known as "Apache Village," building homes, cultivating fields, and adapting their survival skills to the Oklahoma plains.

Life at Fort Sill was a complex blend of confinement and burgeoning self-sufficiency. They were still guarded, their movements restricted, but they had space to breathe, to hunt, and to practice some aspects of their culture away from the direct scrutiny of their captors. It was here that Geronimo, the legendary warrior, spent his final years. Despite his imprisonment, Geronimo became a figure of national fascination. He appeared at expositions, sold signed photographs, and even dictated his autobiography, "Geronimo’s Story of His Life," providing a rare firsthand account of his struggles and beliefs. Yet, even in his celebrity, his deepest desire remained unfulfilled: to return to his homeland. He died at Fort Sill in 1909, never having seen Arizona again, his grave a stark reminder of the unyielding grip of his captors.

The Apache people at Fort Sill, however, were not merely waiting for their own demise. They were actively engaged in shaping their future, even within the confines of their imprisonment. A pivotal decision loomed: whether to accept an offer to return to their ancestral lands in New Mexico and Arizona, or to take allotments of land in Oklahoma and remain there permanently. The choice was agonizing, tearing at the fabric of their community. Ultimately, a significant portion, about one-third, chose to return west and joined the Mescalero Apache Tribe in New Mexico. The remaining 183 individuals, recognizing the economic opportunities and the community they had painstakingly built, chose to stay in Oklahoma, accepting individual land allotments around Fort Sill.

This decision, made in 1913, marked the end of their official status as prisoners of war. With the signing of individual allotment deeds, they were granted U.S. citizenship, a monumental shift after 27 years of being held captive. They were no longer "Apache prisoners of war"; they were now Fort Sill Apache citizens of the United States, landowners in Oklahoma. However, the transition was far from smooth. The allotments, often chosen by government agents, were not always the most fertile, and the Apache, largely unfamiliar with American farming techniques and the intricacies of land ownership, faced immense challenges. The Dawes Act, which facilitated these allotments, often led to the loss of Native American lands through fraud and economic exploitation, and the Fort Sill Apache were not immune to these pressures.

The mid-20th century saw the Fort Sill Apache, like many other Native American tribes, grappling with the legacy of federal policies and the struggle to maintain their cultural identity amidst economic hardship. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 provided a crucial framework for self-governance, allowing tribes to form their own constitutions and elect tribal councils. The Fort Sill Apache seized this opportunity, formally organizing as the Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, solidifying their political identity and laying the groundwork for future sovereignty.

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st, the Fort Sill Apache embarked on a renewed journey of cultural revitalization and economic development. They established their tribal government, developed their own laws and judicial systems, and began to assert their inherent sovereignty. Efforts were made to revive their language, traditional ceremonies, and historical narratives, ensuring that the unique story of their captivity and resilience would not be forgotten by younger generations. They built a tribal headquarters, established health clinics, and invested in educational programs.

Economically, the tribe has embraced various ventures to provide for its members, including gaming enterprises, which have become a vital source of revenue for many Native American nations. These enterprises fund essential tribal services, educational scholarships, and infrastructure development, allowing the Fort Sill Apache to achieve a level of self-sufficiency and economic independence that was unimaginable during their years of captivity. Their status as a federally recognized sovereign nation allows them to enter into agreements with state and federal governments, manage their own resources, and determine their own future.

Today, the Fort Sill Apache Tribe stands as a powerful testament to the indomitable human spirit. Their journey from prisoners of war to a thriving, self-governing nation is a unique and compelling chapter in American history. It speaks to the devastating impact of war and captivity, but more importantly, to the extraordinary resilience of a people who, despite immense suffering and deliberate attempts at cultural annihilation, never relinquished their identity. Their story is a living reminder that sovereignty is not merely a legal status, but an enduring spirit of self-determination, earned through generations of struggle, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to their heritage and their future.