The Unbroken Line: Fishing Practices of Turtle Island Nations

For millennia, across the vast and varied landscapes of what is now known as North America – or Turtle Island, as many Indigenous peoples call their ancestral lands – fishing has been far more than a means of sustenance. It is an intricate tapestry woven into the very fabric of identity, culture, spirituality, economy, and governance for hundreds of First Nations, Native American, Inuit, and Métis communities. Their fishing practices, honed over countless generations, represent an unparalleled legacy of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), sustainable resource management, and a profound, sacred relationship with the aquatic world.

This article delves into the diverse and resilient fishing practices of Turtle Island nations, exploring their historical depth, the devastating impacts of colonialism, and the ongoing efforts to reclaim and revitalize these vital traditions in the face of modern challenges.

A Legacy of Sustainable Ingenuity and Deep Connection

From the salmon-rich rivers of the Pacific Northwest to the ice-laden waters of the Arctic, the vast inland lakes of the Great Lakes region, and the coastal fisheries of the Atlantic, Indigenous fishing practices are characterized by their regional specificity, technological innovation, and an overarching philosophy of reciprocity and stewardship.

In the Pacific Northwest, nations like the Haida, Coast Salish, Tlingit, and Tsimshian have developed highly sophisticated methods for harvesting salmon, the lifeblood of their societies. Ancestral technologies included elaborate fish weirs, traps, and selective gillnets designed to allow sufficient numbers of fish to pass upstream for spawning, ensuring future generations would also be fed. The timing of harvests was dictated by lunar cycles and the observed health of the fish populations, reflecting a deep understanding of ecological rhythms. As one Haida Elder might articulate, "We don’t just take; we ask permission, we give thanks, and we ensure the salmon will always return." This ethos is central to their worldview, where humans are not superior to nature but an integral part of it.

The eulachon, or oolichan, a small, oily fish, held immense cultural and economic significance for many Pacific nations, particularly for its rendering into "grease" – a highly prized commodity used for trade, medicine, and ceremony. The "grease trails" connecting coastal communities to interior nations formed extensive ancient trade networks, underscoring the economic power and cultural centrality of these fisheries.

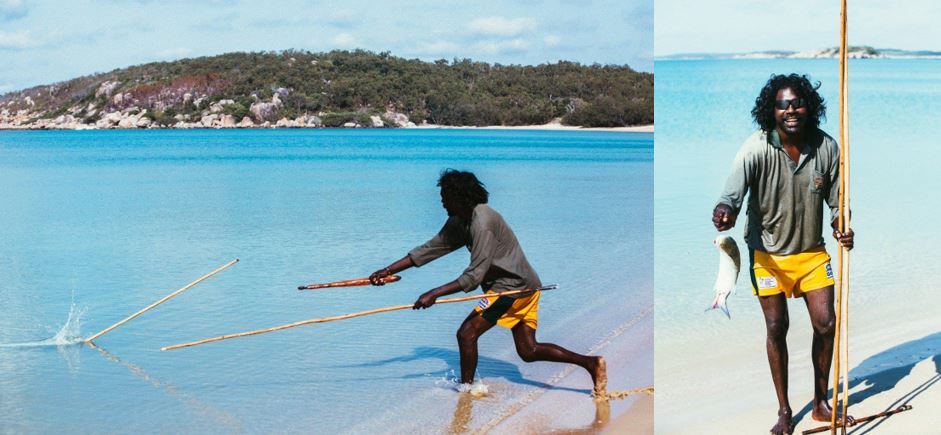

Further east, around the Great Lakes, Anishinaabe (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi) and Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) nations perfected techniques for harvesting whitefish, lake trout, and sturgeon. Spear fishing, gillnets made from natural fibers, and the use of decoys were common. Ice fishing, a practice still widely employed today, required intimate knowledge of ice conditions, fish behavior, and specific gear like jiggers and specialized spears. These practices were often accompanied by ceremonies and storytelling that reinforced the spiritual connection to the water and its inhabitants.

In the Arctic, Inuit communities have mastered hunting marine mammals and fishing in extreme conditions. Harpoons for seals and whales, nets for Arctic char, and sophisticated ice fishing techniques are passed down through generations. Their knowledge of currents, ice formations, and animal migratory patterns is unparalleled, crucial for survival and maintaining a healthy ecosystem. The concept of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) – traditional Inuit knowledge – emphasizes a holistic understanding of their environment, where every action is considered for its impact on the delicate balance of the Arctic ecosystem.

On the Atlantic coast, Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), and Passamaquoddy nations traditionally harvested cod, salmon, eel, and shellfish using weirs, spears, and various netting techniques. The seasonal movements of these fish populations dictated communal activities and resource sharing, ensuring no single area was over-exploited. Their understanding of tidal flows and marine habitats allowed for highly efficient and sustainable harvests.

Across all these diverse regions, TEK provided a robust framework for resource management. It involved:

- Observation and Monitoring: Generations of observing fish populations, water levels, weather patterns, and plant life.

- Rotational Harvesting: Avoiding overfishing in specific areas by moving between fishing grounds.

- Selective Harvesting: Targeting specific species, sizes, or sexes to maintain healthy breeding populations.

- Ceremonial Practices: Rituals of thanks and respect, reinforcing the spiritual connection and ensuring mindful harvesting.

- Oral Histories and Laws: Passing down knowledge, rules, and responsibilities through stories, songs, and communal teachings.

This intricate system was not merely about survival; it was about thriving in harmony with nature, ensuring that the resources would always be there for the "seventh generation" to come.

The Colonial Onslaught: Dispossession and Disruption

The arrival of European colonizers marked a catastrophic turning point for Indigenous fishing practices. The imposition of foreign legal systems, the establishment of reserves, and the relentless push for resource extraction fundamentally disrupted millennia-old relationships with the land and water.

- Resource Grabbing: The insatiable demand for timber, minerals, and agricultural land led to widespread habitat destruction. Logging denuded forests, increasing sedimentation in salmon rivers. Dams, built for hydroelectric power and flood control, blocked fish migration routes, decimating vital populations. The Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River, for instance, wiped out massive salmon runs for Indigenous communities upriver.

- Legal Dispossession: Colonial governments asserted sovereignty over Indigenous territories and resources, often disregarding pre-existing Indigenous laws and treaties. Traditional fishing areas were declared "Crown land" or "public property." Indigenous peoples, who had always fished freely and sustainably, were now deemed "poachers" on their own lands.

- Criminalization of Culture: Traditional fishing practices were outlawed or severely restricted. Indigenous fishers faced fines, imprisonment, and the confiscation of their gear for simply continuing practices that had sustained their communities for generations. This was a deliberate attempt to undermine Indigenous self-sufficiency and force assimilation.

- Residential Schools: The residential school system, designed to "kill the Indian in the child," further severed the intergenerational transmission of TEK. Children were removed from their families and communities, losing the opportunity to learn traditional fishing methods, language, and cultural values directly from Elders and parents.

- Commercial Overfishing: The rapid expansion of industrial-scale commercial fishing by non-Indigenous operators, often unregulated or poorly regulated, led to the collapse of many fish stocks that Indigenous communities relied upon. This competition, combined with a lack of access to their traditional fishing grounds, pushed many Indigenous communities into poverty and food insecurity.

Despite these concerted efforts to dismantle Indigenous societies, the deep connection to fishing endured, often underground, fueled by resistance and resilience.

Asserting Rights: Legal Battles and the Fight for Self-Determination

The late 20th century saw a powerful resurgence of Indigenous rights movements, with fishing rights often at the forefront. Landmark court cases in both Canada and the United States began to affirm and protect Indigenous treaty and aboriginal rights, challenging the colonial legacy.

In Canada, the R. v. Sparrow (1990) decision was a watershed moment. The Supreme Court of Canada affirmed the existence of an Aboriginal right to fish for food, social, and ceremonial purposes, and established that this right takes priority over other uses of the fishery after conservation needs are met. This decision laid the groundwork for Indigenous communities to reassert control over their fisheries.

Another pivotal case was R. v. Marshall (1999), which affirmed the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik, and Passamaquoddy right to fish and hunt for a "moderate livelihood," based on historic treaties signed in the 1760s. This ruling opened avenues for Indigenous-led commercial fisheries and sparked both opportunities and tensions in Atlantic Canada.

In the United States, similar legal battles, such as the Boldt Decision (1974) in Washington State, affirmed the treaty rights of Puget Sound tribes to harvest 50% of the salmon run, leading to co-management agreements and a significant role for tribal nations in fishery management.

These legal victories, hard-won and often through decades of struggle, have been crucial in providing a legal framework for Indigenous nations to rebuild their fisheries and assert their inherent sovereignty.

Contemporary Challenges and the Path Forward

Today, Indigenous fishing practices face a new array of complex challenges, intertwined with the legacies of colonialism:

- Climate Change: Warming waters, ocean acidification, altered precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events are profoundly impacting fish stocks. Salmon are struggling with warmer rivers, Arctic char ranges are shifting, and ocean currents are disrupting marine ecosystems.

- Pollution: Industrial runoff, agricultural chemicals, plastic pollution, and microplastics contaminate waterways, posing health risks to fish and those who consume them.

- Habitat Degradation: Ongoing development, resource extraction (mining, forestry, oil and gas), and urbanization continue to degrade vital fish habitats.

- Jurisdictional Disputes: Despite legal rulings, Indigenous nations often still face resistance from federal and provincial/state governments and non-Indigenous commercial fishers regarding their rightful role in fishery management and access to resources.

- Food Security: For many remote Indigenous communities, particularly in the North, traditional foods like fish are critical for food security, health, and cultural continuity. Disruptions to these fisheries have severe consequences.

Despite these formidable obstacles, Indigenous nations across Turtle Island are leading the way in revitalization and innovation:

- Reclaiming Management: Nations are increasingly asserting their jurisdiction and establishing their own fishery management plans, often integrating TEK with Western scientific approaches. Co-management agreements with governments are becoming more common, recognizing Indigenous nations as vital partners.

- Cultural Revitalization: Communities are actively working to pass on traditional knowledge to younger generations through language immersion programs, on-the-land camps, and mentoring initiatives. The return of traditional ceremonies linked to fishing seasons reinforces cultural identity and stewardship.

- Sustainable Economic Development: Indigenous-led commercial fisheries are emerging, focused on sustainable practices that prioritize long-term ecological health over short-term profits. These initiatives provide economic opportunities while upholding cultural values.

- Restoration Efforts: Many nations are actively engaged in habitat restoration, salmon enhancement projects, and water quality monitoring, demonstrating their unwavering commitment to healing the environment.

- Advocacy and Leadership: Indigenous voices are increasingly prominent on the global stage, advocating for climate action, environmental protection, and the recognition of Indigenous rights as fundamental to global sustainability.

Conclusion

The fishing practices of Turtle Island nations are a profound testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and an enduring spiritual connection to the natural world. They represent not just methods of harvesting, but entire systems of governance, culture, and sustainable living that have sustained communities for millennia.

The colonial era inflicted immense damage, attempting to sever these vital connections, but the spirit of Indigenous fishing endures. Through legal battles, cultural revitalization, and unwavering advocacy, Indigenous nations are reclaiming their rightful place as stewards of the aquatic environment. Their deep traditional ecological knowledge, their commitment to the seventh generation, and their holistic understanding of ecosystem health offer invaluable lessons for all humanity in an era of unprecedented environmental crisis. To truly move towards a sustainable future, it is imperative to listen to, learn from, and empower the original caretakers of Turtle Island and their unbroken line of connection to the waters and the life within them.