Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English about the first encounters between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag.

Echoes of Patuxet: The Formative First Encounters Between Pilgrims and Wampanoag

Plymouth, Massachusetts – The story of America’s founding is often painted with broad strokes of resilience and divine providence, particularly when recounting the arrival of the Pilgrims. Yet, the vibrant tapestry of that pivotal moment in 1620-1621 is far more intricate, woven with threads of desperation, diplomacy, disease, and profoundly differing worldviews. It is the story of two peoples – the English Separatists seeking religious freedom, and the indigenous Wampanoag, sovereign over their ancestral lands for millennia – whose lives irrevocably converged on the shores of what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts. Their first encounters, fraught with apprehension and underscored by the specter of past European brutality, would lay the groundwork for a fragile alliance that shaped the destiny of a continent.

The Pilgrims, a group of around 102 English Separatists and other economic migrants, arrived aboard the Mayflower in November 1620, far north of their intended destination in Virginia. After a grueling 66-day voyage that claimed two lives, they found themselves in an unfamiliar wilderness during the brutal onset of a New England winter. They chose a site on Cape Cod Bay, a former Wampanoag village called Patuxet, as their settlement. This choice, however, was not one of innocent discovery. The village had been tragically emptied just a few years prior by a devastating plague, likely brought by European traders, which had swept through the coastal Wampanoag communities between 1616 and 1619, killing an estimated 75-90% of the population.

For the Pilgrims, the first winter was a trial by fire. Malnutrition, scurvy, and pneumonia decimated their ranks. By March 1621, nearly half of the original settlers had perished. William Bradford, the colony’s long-serving governor, recounted the grim reality in his seminal work, Of Plimoth Plantation: "But that which was most sadd & lamentable was, that in 2 or 3 moneths time halfe of their company dyed, espetialy in Jan: & February, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses & other comforts; being infected with the scurvy & other diseases, which brought them in short time to their graves." They were desperate, isolated, and profoundly vulnerable.

Meanwhile, the Wampanoag, led by their powerful sachem (leader) Massasoit Ousamequin, had been observing these strange newcomers with a mixture of curiosity and deep-seated caution. Their territory, Pokanoket, encompassed much of southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island, and they had a rich, complex society rooted in agriculture, hunting, and sophisticated governance. Massasoit, whose name means "Great Leader," was a shrewd diplomat and strategist. He understood the precarious position his people were in. The devastating plague had severely weakened the Wampanoag, making them vulnerable to rival tribes like the Narragansett, who had largely escaped the sickness. The arrival of the English, while a potential threat, also presented a strategic opportunity.

The initial encounters were tentative, marked by mutual suspicion. The Pilgrims had heard rumors of the "savages" from earlier European accounts and were wary. The Wampanoag, in turn, had suffered at the hands of European slavers and explorers, whose visits often brought violence and disease. Indeed, the very site the Pilgrims settled, Patuxet, was the former home of Tisquantum, better known as Squanto, who had been kidnapped by an English captain, Thomas Hunt, in 1614, sold into slavery in Spain, and eventually made his way back to his homeland through remarkable resilience and fortune, only to find his entire village wiped out.

The true turning point arrived on March 16, 1621. A lone figure walked into the Pilgrims’ nascent settlement. He was Samoset, an Abenaki sachem from what is now Maine, who had learned some English from fishermen and traders. "Welcome, Englishmen," he declared, according to Edward Winslow’s Mourt’s Relation, a contemporary account. The Pilgrims were astonished. Samoset explained the local geography, spoke of the Wampanoag, and described their leader, Massasoit. He also introduced them to Tisquantum, or Squanto, a few days later.

Squanto’s role was nothing short of miraculous for the struggling Pilgrims. As a Patuxet native, he knew the land intimately. His incredible journey, having learned English during his captivity and subsequent travels, made him an indispensable interpreter and cultural bridge. He became, as Bradford wrote, "a spetiall instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation." Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to cultivate indigenous crops like corn, beans, and squash, using fish as fertilizer. He showed them how to distinguish edible plants from poisonous ones, where to hunt deer and fowl, and how to fish the local waters. His knowledge was paramount to the Pilgrims’ survival.

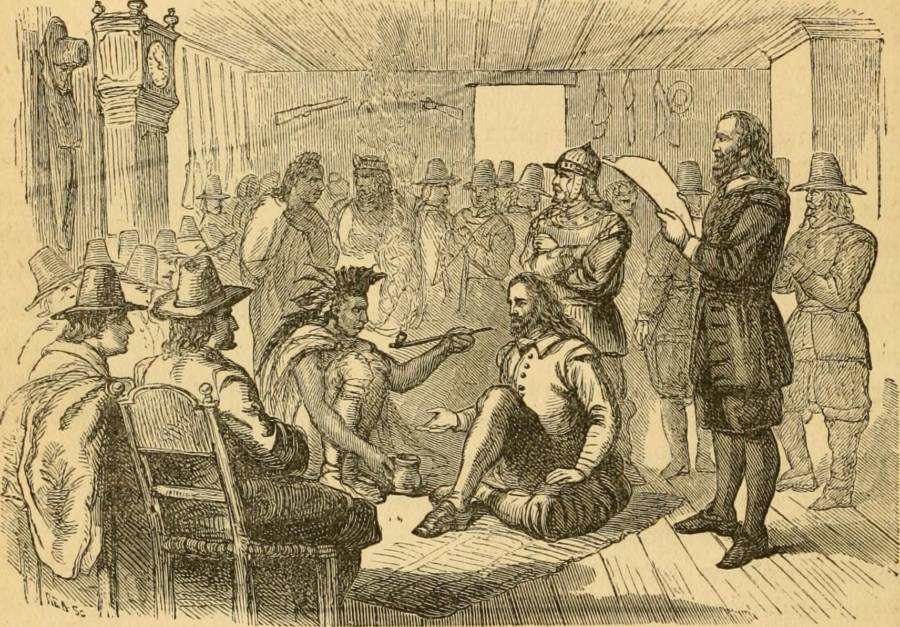

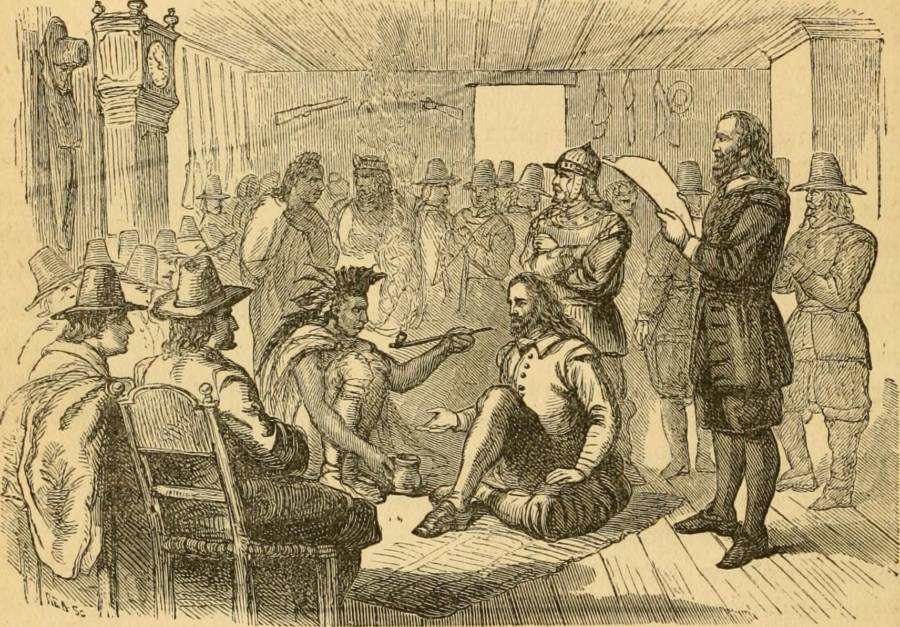

With Squanto as mediator, the historic meeting between Governor John Carver (soon to be succeeded by Bradford) and Massasoit Ousamequin took place on March 22, 1621. It was a formal affair, designed to impress and secure a lasting peace. Winslow described the scene: "The King was a very lusty man, in his best years, an able body, grave of countenance, and spare of speech." Both parties approached with a mix of apprehension and strategic intent. The ensuing negotiations led to a treaty, a pact of mutual defense and peaceful coexistence that would endure for over 50 years.

The terms of the treaty, as recorded by Winslow, were remarkably progressive for their time:

- That neither he nor any of his should injure or do hurt to any of their people.

- That if any of his did hurt to any of theirs, he should send the offender, that they might punish him.

- That if anything were taken away from any of theirs, he should cause it to be restored; and they should do the like to him.

- If any did unjustly war against him, they would aid him; and if any did war against them, he should aid them.

- He should send to his neighbor confederates, to certify them of this, that they might not wrong them, but might be likewise comprised in the conditions of peace.

- That when their men came to them, they should leave their bows and arrows behind them.

This treaty was not merely an act of goodwill; it was a pragmatic alliance born of necessity for both sides. For the Pilgrims, it secured their fledgling colony against an unknown wilderness and potential indigenous hostility. For Massasoit, it offered a potential military ally against the more powerful Narragansett, and access to European trade goods like metal tools and weapons, which could bolster his people’s position.

The alliance was solidified later that year during what is now famously, though often inaccurately, referred to as the "First Thanksgiving." In the autumn of 1621, after a successful harvest, the Pilgrims held a celebratory feast. Winslow recounts that Governor Bradford sent four men "fowling" and that "they came with a great many of wild turkies, and other fowl." Massasoit, hearing the celebratory gunfire, arrived with ninety of his men, and contributed five deer to the feast. For three days, Pilgrims and Wampanoag shared food and company, engaging in friendly competitions and strengthening their bond. It was a moment of genuine cultural exchange and shared survival, a testament to the fragile peace they had forged.

Yet, beneath the surface of this apparent harmony lay profound differences in culture, worldview, and intentions that would ultimately unravel the peace. The Pilgrims viewed land as a commodity to be owned and developed, while the Wampanoag saw it as a living entity to be shared and stewarded. The English brought with them a rigid social hierarchy and an evangelical zeal, while the Wampanoag operated within a complex spiritual framework and communal ownership. Over time, as more English settlers arrived, the demographic and power balance shifted dramatically. The Pilgrims’ initial reliance on the Wampanoag gave way to increasing dominance and territorial expansion.

The legacy of these first encounters is complex and often contradictory. It represents a rare moment of cooperation and mutual aid between vastly different cultures, born out of necessity and strategic foresight. It laid the foundation for the Plymouth Colony and, by extension, the future United States. However, it also marked the beginning of centuries of dispossession, conflict, and cultural devastation for the indigenous peoples of North America. The treaty, once a symbol of hope, would eventually buckle under the weight of colonial expansion, culminating in the devastating King Philip’s War (Metacom’s War) in 1675-1676, led by Massasoit’s son, Metacom.

Today, understanding the first encounters between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag requires acknowledging both the genuine moments of collaboration and the inherent tensions that led to profound long-term consequences. It is a story not of simple heroes and villains, but of human beings navigating an unprecedented confluence of cultures, each striving for survival and a future for their people, forever shaping the trajectory of a continent. The echoes of Patuxet continue to resonate, urging us to confront the full, nuanced truth of our shared history.