Visual Sovereignty: Ethnographic Films Reclaim Turtle Island Traditions

The lens, for centuries, has been a tool of observation, documentation, and, often, domination. In the context of Turtle Island – the Indigenous name for North America – early ethnographic filmmaking largely reflected a colonial gaze, framing Indigenous peoples as exotic, vanishing, or static relics of the past. These films, often produced by non-Indigenous anthropologists and filmmakers, contributed to a distorted public perception, stripping communities of their agency and misrepresenting their vibrant, evolving traditions. However, a profound shift has occurred. Today, a powerful movement of Indigenous filmmakers is reclaiming the camera, transforming ethnographic film into a tool of self-determination, cultural revitalization, and visual sovereignty.

This modern wave of Indigenous-led ethnographic filmmaking is not merely about documenting traditions; it is about narrating identity, asserting rights, and preserving knowledge from an internal perspective. It challenges the historical power imbalance, providing platforms for Indigenous voices to tell their own stories, on their own terms, respecting protocols and community wishes. The result is a rich, complex, and deeply authentic cinematic tapestry that offers invaluable insights into the enduring traditions, contemporary realities, and future aspirations of Turtle Island’s diverse Indigenous nations.

From Colonial Gaze to Self-Representation

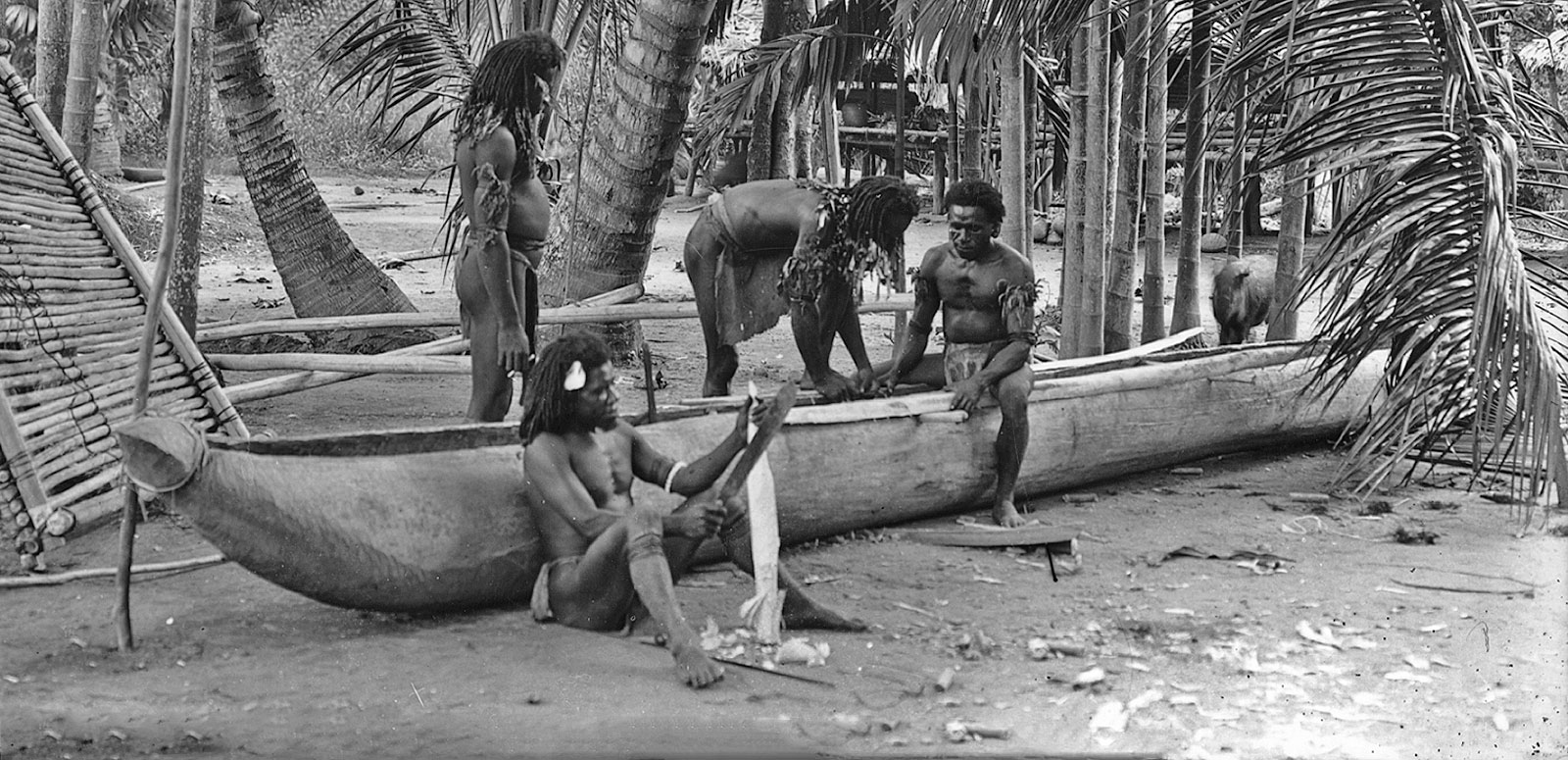

Early anthropological films, such as Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922) – though not specifically about Turtle Island’s settled nations, it set a problematic precedent for ethnographic film – often involved staged scenes, romanticized portrayals, and a focus on "primitive" lifeways. Indigenous subjects were rarely consulted, let alone empowered to shape their own narratives. This era cemented stereotypes and contributed to the erasure of Indigenous modernity and resilience.

The turning point began to gather momentum in the latter half of the 20th century, spurred by global decolonization movements and increased Indigenous activism. Filmmakers like the legendary Abenaki director Alanis Obomsawin, who began her career with the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) in the late 1960s, became pioneers in advocating for Indigenous control over Indigenous stories. Obomsawin’s prolific career, marked by films like Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), directly confronted colonial narratives and amplified Indigenous perspectives on historical and contemporary struggles. She famously stated, "The more we tell our story, the more we heal." Her work exemplifies the transition from external observation to internal testimony.

The concept of "visual sovereignty," articulated by scholars like Michelle Raheja, is central to this shift. It describes the right of Indigenous peoples to self-represent and self-define through media, challenging dominant media representations and reclaiming control over their images. This isn’t just about what is filmed, but how it’s filmed, by whom, and for what purpose. It involves ethical engagement, community consent, and a deep understanding of cultural protocols.

Documenting the Sacred: Ceremony and Spirituality

One of the most profound contributions of contemporary ethnographic films on Turtle Island traditions is their respectful and nuanced portrayal of ceremony and spirituality. These films often navigate the delicate balance between sharing knowledge and protecting sacred practices from exploitation or misinterpretation. They move beyond the superficial or exotic, delving into the philosophical underpinnings and community significance of these traditions.

Films might document the preparations for a Sundance ceremony, highlighting the physical and spiritual discipline required, the role of elders, and the deep connection to the land and ancestral teachings. Others might explore the resurgence of potlatch ceremonies among Northwest Coast nations, illustrating how these elaborate gift-giving feasts reaffirm social structures, validate hereditary rights, and distribute wealth – a direct challenge to the historical Canadian ban on the practice. These films serve as vital educational tools, both for younger generations within the community and for external audiences, fostering understanding and respect. They demonstrate that these ceremonies are not relics of the past but living, breathing expressions of cultural identity and spiritual fortitude.

Land, Language, and Lifeways: Pillars of Identity

The connection to land, the power of language, and the sustainability of traditional lifeways are recurrent and essential themes. Ethnographic films beautifully illustrate how these elements are inextricably linked to Indigenous identity and survival.

Many films focus on land defense and environmental stewardship, often showcasing Indigenous knowledge systems that emphasize reciprocal relationships with the natural world. From protests against pipelines threatening sacred sites and water sources to efforts to restore traditional hunting and fishing practices, these films highlight the ongoing struggle for land rights and the crucial role of Indigenous perspectives in addressing global environmental crises. There’s Something in the Water (2019), co-directed by Elliot Page and Ian Daniel, featuring Indigenous activists like Mi’kmaw water protector Louise Delisle, powerfully exposes environmental racism in Nova Scotia, demonstrating the direct link between land, health, and social justice.

Language revitalization is another critical area. With hundreds of Indigenous languages across Turtle Island facing endangerment due to historical colonial policies like residential schools, films become invaluable archives and catalysts for linguistic revival. Documentaries capture elders sharing stories in their ancestral tongues, intergenerational language classes, and the innovative ways communities are bringing languages back from the brink. Sgàwaay K’uuna (Edge of the Knife) (2018), the first feature film spoken entirely in the Haida language, is a monumental achievement that blends traditional storytelling with cinematic artistry, demonstrating the power of language to carry culture and worldview.

Films also meticulously document traditional lifeways: hunting, trapping, fishing, foraging, farming, and the intricate knowledge systems associated with these practices. They show the skill, patience, and deep respect for the environment inherent in these activities, challenging the narrative of Indigenous peoples as simply "hunter-gatherers" and instead presenting them as sophisticated land managers and knowledge holders.

Contemporary Realities and Resilience

Beyond historical traditions, ethnographic films on Turtle Island also bravely confront contemporary challenges while celebrating resilience. They shed light on the enduring impacts of colonialism, such as intergenerational trauma from residential schools, the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People (MMIWG2S), and systemic inequalities in healthcare, education, and justice systems.

Films like We Were Children (2012) offer raw, first-person accounts of residential school survivors, providing crucial historical testimony that demands recognition and reconciliation. Others explore urban Indigenous experiences, showcasing the strength of community organizing, cultural resurgence in city spaces, and the ongoing fight for self-determination in diverse settings. These narratives dismantle the "vanishing Indian" myth, revealing dynamic, adaptive communities that navigate modernity while holding fast to their cultural roots.

The Future of Indigenous Ethnographic Film

The landscape of Indigenous ethnographic film on Turtle Island continues to evolve rapidly. Organizations like the Sundance Institute’s Indigenous Program, Vision Maker Media, and the National Film Board of Canada’s Indigenous Studio are crucial in fostering new talent, providing resources, and ensuring wider distribution. There’s a growing emphasis on mentorship, training, and intergenerational knowledge transfer within filmmaking communities.

The rise of digital platforms and accessible technology has further democratized filmmaking, allowing more Indigenous storytellers to pick up cameras and share their perspectives. This has led to a proliferation of short films, web series, and VR experiences that push the boundaries of ethnographic storytelling, engaging audiences in innovative ways.

Ultimately, ethnographic films on Turtle Island traditions are more than just documents; they are acts of cultural affirmation, political statements, and pathways to healing. They dismantle stereotypes, educate, and inspire, proving that the camera, when wielded by those whose stories it tells, can be a powerful instrument of truth and reconciliation. As these films continue to emerge, they not only preserve the rich tapestry of Indigenous traditions but also actively shape a future where Indigenous voices are heard, respected, and celebrated across Turtle Island and beyond. The visual sovereignty they embody is not merely a cinematic concept, but a living, breathing testament to the enduring spirit and wisdom of the continent’s first peoples.