Nomadic Sustenance: The Essential Protein-Rich Travel Foods of Plains Nations

Before the advent of energy bars, MREs, or freeze-dried meals, the indigenous peoples of the North American Great Plains had already mastered the science of high-performance, protein-rich travel food. For nations such as the Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche, Blackfoot, and Crow, life was often one of movement – following bison herds, engaging in trade, conducting warfare, or migrating to seasonal camps. This dynamic existence demanded food that was not only nutrient-dense but also lightweight, non-perishable, and easy to transport. Their ingenious solutions, primarily derived from the bison, stand as a testament to their profound ecological knowledge and practical ingenuity, offering a blueprint for survival that remains relevant even today.

The vast, open plains, while teeming with life, presented unique challenges. Sustaining large groups of people, often on foot or horseback, over long distances and through variable climates, required an intuitive understanding of food preservation and nutrition. The cornerstone of their diet, and consequently their travel provisions, was the American bison (or buffalo). This majestic animal was more than just a source of food; it was a department store, providing everything from shelter and tools to fuel and spiritual connection. Its efficient utilization was central to the survival strategies of Plains Nations, particularly when it came to creating portable, long-lasting sustenance.

Jerky: The Original Power Bar

One of the most fundamental and ubiquitous travel foods was dried meat, commonly known today as jerky. The process was simple yet incredibly effective. After a successful hunt, strips of lean meat, typically from the bison but also deer, elk, or antelope, were cut thin, against the grain, to facilitate drying. These strips were then hung on racks to air dry in the sun and wind, often over a slow, smoldering fire to add a smoky flavor and further deter insects and spoilage. The dry, arid climate of the plains was ideal for this method, effectively removing moisture, which is the primary catalyst for bacterial growth and decay.

The resulting product was a lightweight, highly concentrated protein source. A few strips of jerky could sustain a warrior or traveler for a full day, providing essential amino acids and energy without the bulk or weight of fresh meat. It could be eaten as is, gnawed on for a quick burst of energy, or rehydrated and cooked into stews when circumstances allowed. The Lakota referred to this dried meat as Napa, a staple that could last for months, if not years, when properly stored in rawhide containers. Its portability and long shelf-life made it indispensable for extended journeys, hunting expeditions, and war parties, ensuring that vital sustenance was always at hand.

Pemmican: The Ultimate Superfood Concentrate

While jerky was a foundational travel food, the pinnacle of Plains Nations’ culinary engineering for long-term sustenance was undoubtedly pemmican. Derived from the Cree word pimîhkân, meaning "manufactured grease," pemmican was a hyper-concentrated, nutrient-dense survival ration that European explorers, fur traders, and military expeditions would later adopt due to its unparalleled effectiveness.

The creation of pemmican was a meticulous process that combined dried meat with rendered fat, and sometimes berries or other local edibles. The first step involved taking the carefully dried meat (jerky) and pounding it into a fine powder or shredded fibers using stone mauls. This pulverized meat formed the base. Separately, bison fat, particularly the highly nutritious suet from around the kidneys, was rendered down into a liquid oil. This hot, liquid fat was then poured over the powdered meat, typically in a ratio of about 1:1 or 2:1 (fat to meat), and thoroughly mixed.

Often, for added flavor, vitamins, and an extra caloric boost, ingredients like dried chokecherries, Juneberries, or saskatoon berries were incorporated into the mixture. These berries provided a welcome counterpoint to the richness of the meat and fat, and their natural sugars and antioxidants contributed to the pemmican’s overall nutritional profile and shelf stability.

Once mixed, the warm pemmican was packed tightly into rawhide bags, known as parfleches, or into animal intestines. As it cooled, the fat solidified, binding all the ingredients into a dense, solid block. This compact form was incredibly efficient for transport, taking up minimal space while delivering maximum nutritional value.

The nutritional profile of pemmican was extraordinary. It was an almost perfect balance of macronutrients, providing high levels of fat for sustained energy, protein for muscle repair and growth, and carbohydrates (if berries were included) for immediate fuel. Its caloric density was astounding; a small portion could provide hundreds of calories, enough to fuel strenuous physical activity for hours. Crucially, the high fat content acted as a natural preservative, sealing the dried meat from air and moisture, allowing pemmican to remain edible for years, even decades, without refrigeration.

Historian George E. Hyde, in "Red Cloud’s Folk: A History of the Oglala Sioux Indians," notes the vital role of pemmican: "This was the best food for travel. A small piece eaten raw or boiled in water to make a thin soup was enough for a meal, and it kept indefinitely." Similarly, Arctic explorer Sir John Richardson, writing in 1829, described pemmican as "the most nourishing and portable food hitherto invented." This praise from external observers underscores the indigenous genius behind its creation.

Beyond Bison: Other Protein Sources and Preparations

While bison was paramount, Plains Nations utilized a variety of other protein sources when available, often employing similar preservation techniques.

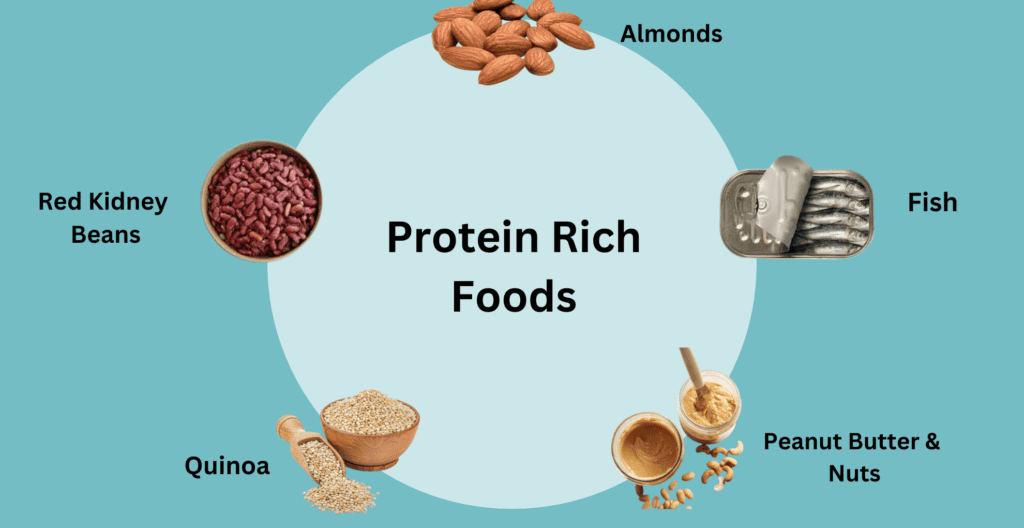

- Fish: In regions with rivers and lakes, fish were caught and often dried or smoked, especially during spawning seasons when catches were abundant. Similar to meat jerky, dried fish provided a lightweight, protein-rich food source for travel, though perhaps less common for the deep plains nations than those nearer major waterways.

- Marrow: The marrow from bison bones was a highly prized delicacy and a rich source of fat and nutrients. While often consumed fresh immediately after a kill, it could also be rendered and used in pemmican or simply stored as rendered fat. Its high caloric value made it a quick energy booster.

- Small Game: Rabbits, prairie dogs, and birds contributed to the diet, though their meat was less ideal for large-scale preservation for long-distance travel due to smaller yields. However, any available protein source would be dried if circumstances permitted.

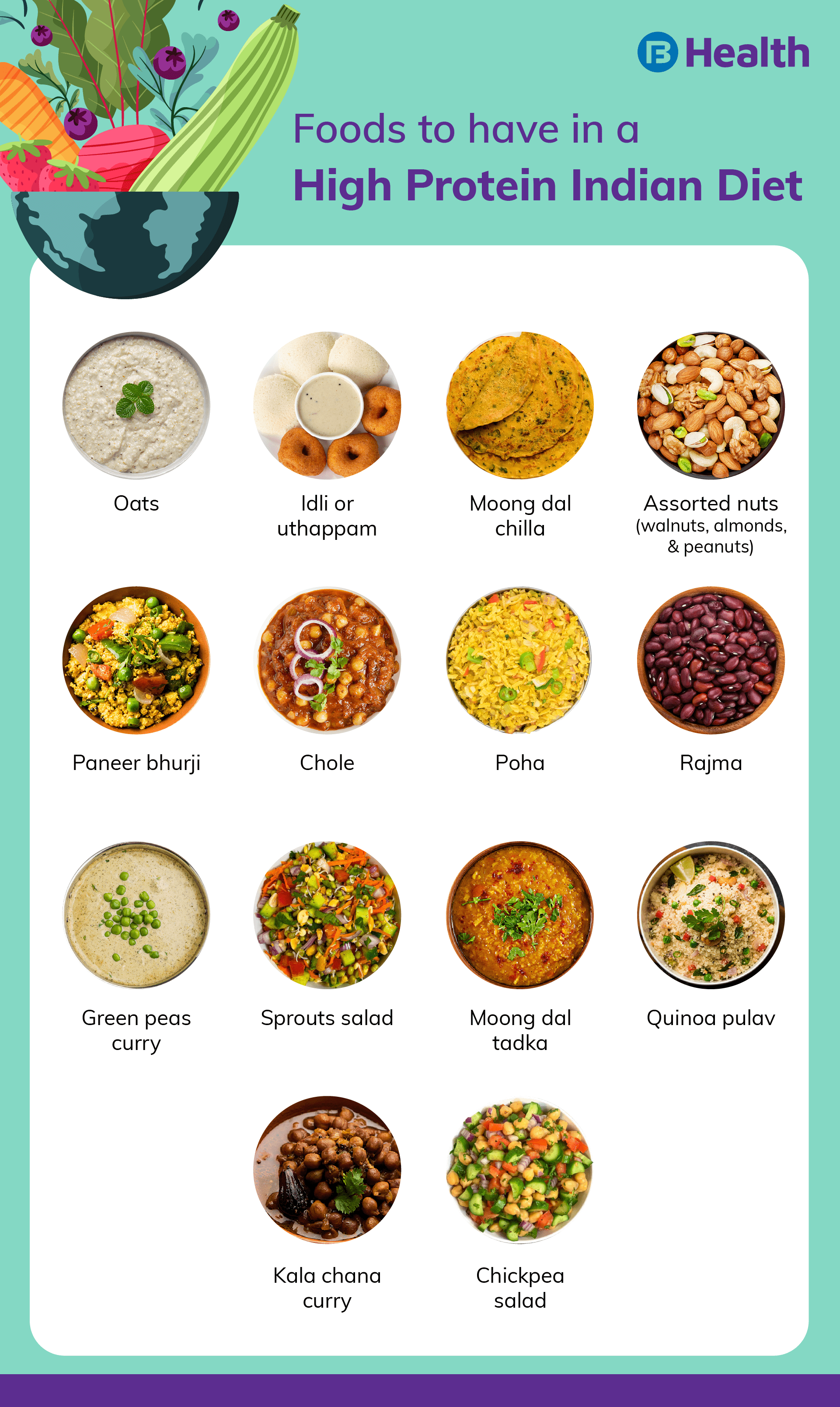

- Plant-Based Proteins (Supplemental): While the focus was heavily on animal proteins, some plant foods offered supplemental protein. Nuts, such as walnuts or pecans found in riverine areas, and various seeds could be gathered and stored, providing additional fats, carbohydrates, and some protein. However, these were typically less central to the travel food diet than meat products due to their lower caloric density relative to their weight compared to pemmican.

The Ingenuity and Science Behind It

The development of these essential travel foods by Plains Nations was not merely an act of survival; it was an intuitive mastery of food science. They understood, through generations of observation and experimentation, the principles of dehydration, fat preservation, and nutrient density long before these terms were formalized in Western science. Their methods prevented spoilage by removing water activity and encapsulating the food in protective fat. They recognized the critical role of fat in providing sustained energy for strenuous activities and during periods of scarcity.

Furthermore, their approach embodied a profound respect for the land and its resources. The "nose-to-tail" utilization of the bison meant that virtually no part of the animal went to waste, a sustainable practice that stands in stark contrast to much of modern food production. This holistic approach ensured maximum yield from each hunt, crucial for nomadic peoples who relied entirely on the natural world for their sustenance.

Enduring Legacy

The protein-rich travel foods of the Plains Nations represent a remarkable chapter in human adaptation and ingenuity. They were more than just fuel; they were a symbol of resilience, self-sufficiency, and a deep connection to their environment. These foods allowed warriors to defend their territories, hunters to pursue migrating herds, families to move between seasonal camps, and traders to connect distant communities. They underpinned the very fabric of their nomadic societies, enabling a dynamic and vibrant way of life.

In an era where convenience often trumps nutritional value, and where processed foods dominate, the lessons from the Plains Nations offer a powerful reminder of what truly essential food looks like. Their pemmican and jerky were the original high-performance, minimalist rations, perfected not in a laboratory, but through centuries of living in harmony with the land. Their legacy continues to inspire modern survivalists, outdoor enthusiasts, and anyone seeking a deeper understanding of sustainable and truly effective sustenance. The genius of their culinary heritage endures, a testament to a profound knowledge that sustained nations across the vast American plains.