The Arctic, a landscape of breathtaking beauty and formidable challenges, has historically demanded unparalleled ingenuity from its inhabitants. For millennia, indigenous peoples such as the Inuit, Yupik, and Iñupiat have thrived in this extreme environment, not despite its harshness, but by mastering it. Central to their survival and cultural continuity has been an extraordinary understanding of food preservation.

Far from modern conveniences like refrigeration or canning, these communities developed sophisticated and sustainable methods to store vital food resources. These techniques were not merely about preventing spoilage; they were integral to managing seasonal abundance, ensuring food security during lean times, and maintaining a healthy, nutrient-rich diet essential for life in the unforgiving North.

This comprehensive exploration delves into the traditional Eskimo food preservation techniques, revealing the scientific principles behind their ancestral practices and their profound cultural significance. We will uncover how these ingenious methods transformed fresh catches into long-lasting provisions, sustaining generations and shaping a unique way of life.

The Necessity of Preservation in the Arctic

Life in the Arctic is characterized by extreme cold, long periods of darkness, and dramatic seasonal fluctuations in food availability. When seals, whales, caribou, or fish were successfully hunted, the sheer volume of meat often far exceeded immediate consumption needs. Without effective preservation, this vital resource would quickly spoil, leading to waste and potential starvation.

Therefore, food preservation was not a luxury but a fundamental pillar of survival. It allowed communities to store surplus food from successful hunts, creating reserves that could be drawn upon during periods of scarcity, such as the long winter months or unexpected poor hunting seasons. This foresight and planning were paramount to their resilience.

Natural Refrigeration: The Arctic’s Ultimate Freezer

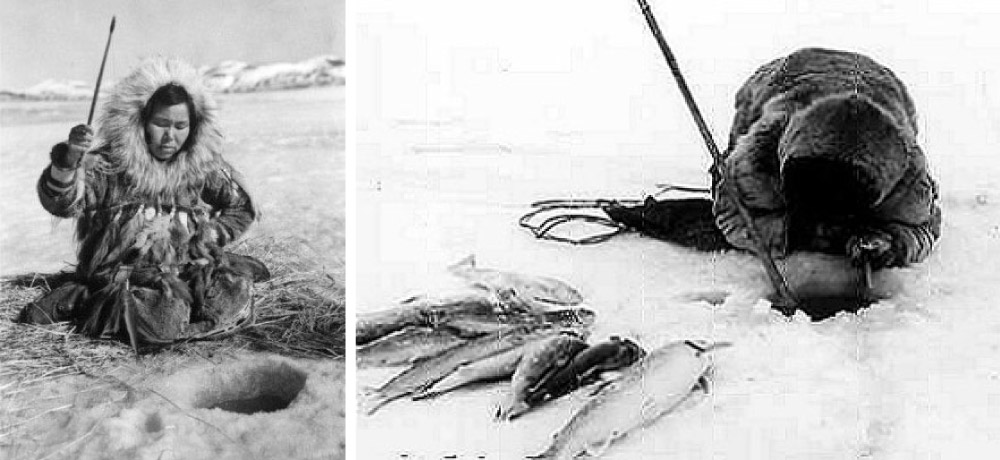

Perhaps the most obvious and widely utilized preservation method was natural freezing. The Arctic’s consistently sub-zero temperatures provided a ready-made, vast freezer. Freshly hunted meat, fish, and even berries could simply be left outdoors to freeze solid.

Once frozen, these foods could be stored indefinitely, maintaining their nutritional value and preventing bacterial growth. This method was incredibly effective and required minimal effort beyond the initial processing. Large caches of frozen meat were often buried in the permafrost or covered with snow and rocks, providing natural insulation and protection from scavengers.

Constructing Ice Cellars and Caches

Beyond simply leaving food outside, sophisticated ice cellars and permafrost caches were constructed. These underground storage facilities, often dug into the permafrost, maintained consistently low temperatures year-round, even during brief summer thaws. They offered protection from animals and allowed for organized, long-term storage of substantial quantities of food.

Drying: Harnessing Wind and Sun

Drying is another ancient and effective preservation technique that removes moisture, inhibiting microbial growth. In the Arctic, this often involved air-drying, particularly during the relatively warmer and windier months.

Meat, especially thin strips of caribou or fish, would be hung on racks or lines to dry in the sun and wind. The cold, dry air of the Arctic, even when above freezing, was ideal for this process. The resulting ‘pemmican’ or dried meat (like pipsi, dried fish) was lightweight, highly nutritious, and could be stored for extended periods, making it perfect for journeys or as emergency rations.

Preparing Dried Fish and Meat

Fish, such as Arctic char or salmon, were often gutted, split, and then hung to dry. Similarly, caribou meat was cut into thin strips. The drying process concentrated the nutrients, creating a highly energy-dense food source crucial for active lifestyles in a cold climate. This method also made the food more portable.

Fermentation: A Transformative Preservation Method

Fermentation, a process often associated with warmer climates, played a surprisingly significant role in Arctic food preservation. This technique involves controlled microbial activity that transforms food, enhancing flavor and extending shelf life. It also often makes nutrients more bioavailable.

One of the most famous examples is kiviak, where small birds (like auklets) are encased whole in a seal skin, sealed with blubber, and allowed to ferment for several months. Another is igunaq, a traditional dish of fermented walrus or seal meat, prepared by burying it in a cache and allowing it to age.

The Science Behind Arctic Fermentation

These fermentation processes occur in anaerobic (oxygen-free) conditions, often facilitated by natural enzymes and bacteria present in the food or environment. The resulting products are not only preserved but develop unique, pungent flavors highly prized within Inuit culture. While initially surprising to outsiders, these foods represent a deep understanding of microbiology and food chemistry, providing vital nutrients and beneficial bacteria.

Rendering and Blubber Storage

Fats and blubber from marine mammals were incredibly valuable for energy, warmth, and as a cooking medium. Blubber could be rendered down into oil, which could then be stored in containers made from seal gut or other natural materials. This rendered oil provided a stable, high-calorie food source that resisted spoilage.

Solid blubber could also be stored in caches or simply frozen. Its high fat content meant it was less prone to rapid deterioration than lean meat. The controlled rancidification of certain fats was also a recognized method, where specific enzymatic breakdown was allowed to occur, creating distinct flavors and textures that were appreciated.

Other Traditional Methods and Storage Practices

Beyond the primary methods, various auxiliary techniques contributed to overall food security. For instance, berries (such as cranberries and cloudberries) were often mixed with rendered fat or stored frozen in natural containers. These provided essential vitamins and antioxidants.

Seaweed was also collected and sometimes dried or stored. The careful placement of food in specific locations, utilizing natural temperature gradients and protection from elements and animals, was a constant consideration in all preservation efforts.

Tools and Materials for Preservation

The tools for these tasks were often simple yet effective. Knives made from stone, bone, or later, metal, were essential for butchering and slicing. Drying racks were constructed from driftwood or animal bones. Containers for oil or fermented foods were ingeniously crafted from seal skins, bladders, or even hollowed-out gourds or wooden vessels.

The knowledge of how to select the right materials and construct these tools was passed down through generations, embodying the practical wisdom accumulated over centuries of Arctic living.

Cultural Significance and Traditional Knowledge

Food preservation was far more than a practical skill; it was a cornerstone of Inuit culture and social structure. The successful preservation of food was a communal effort, requiring cooperation, shared knowledge, and respect for the natural world. It reinforced community bonds and ensured collective survival.

The techniques are deeply intertwined with traditional knowledge (Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit), encompassing an understanding of animal behavior, seasonal changes, weather patterns, and the properties of different materials. This holistic knowledge system guided every aspect of their foodways, from hunting to preparation and storage.

Modern Relevance and Adaptations

While modern technologies have reached many Arctic communities, traditional food preservation techniques continue to be practiced, especially in more remote areas or for cultural reasons. The desire to maintain a connection to ancestral traditions and to enjoy the unique flavors of traditionally preserved foods remains strong.

Furthermore, these methods offer valuable lessons in sustainable living, minimal waste, and resilience in the face of environmental challenges. As interest in indigenous foodways grows, the ingenuity of Inuit food preservation stands as a testament to human adaptability and respect for nature.

What did Eskimos eat for food? The traditional diet was rich in protein and fat, primarily consisting of marine mammals (seals, whales, walrus), caribou, fish (Arctic char, salmon), and birds. Berries and some plants were consumed seasonally.

How did indigenous people preserve food? Indigenous peoples worldwide used diverse methods tailored to their environments. In the Arctic, this included extensive freezing, air-drying, fermentation, and rendering of fats, as detailed above.

How did Inuit survive in the Arctic? Survival was multifaceted, relying on sophisticated hunting tools and techniques, specialized clothing, ingenious shelter construction (igloos, sod houses), community cooperation, and critically, highly effective food preservation methods.

What is traditional Inuit food? Traditional Inuit food includes a wide array of meats and fish, often consumed raw, frozen, dried, or fermented. Examples are mukluk (whale skin and blubber), aqutak (Eskimo ice cream made from whipped fat, berries, and sometimes fish), pipsi (dried fish), and fermented foods like kiviak and igunaq.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Ingenuity and Resilience

The traditional food preservation techniques of the Inuit, Yupik, and Iñupiat peoples are a powerful testament to human resilience, adaptability, and profound ecological knowledge. Faced with one of the planet’s most challenging environments, these communities developed intricate systems that not only ensured physical survival but also fostered rich cultural practices.

From the vast natural freezer of the Arctic landscape to the complex biochemistry of fermentation, these methods represent centuries of empirical observation and innovation. They allowed communities to thrive, building a sustainable relationship with their environment that continues to inspire and inform us today.

Understanding these ancestral practices offers a window into a remarkable way of life and underscores the enduring value of traditional knowledge in navigating environmental extremes and ensuring food security.