The Arctic, a land of stark beauty and unforgiving conditions, presents one of the most extreme environments on Earth. For millennia, indigenous peoples, often broadly referred to as ‘Eskimo’ though more accurately identified by specific groups like the Inuit, Yup’ik, and Iñupiat, have not merely survived but thrived in this challenging landscape. Their remarkable ability to adapt is a testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and a profound understanding of their environment, particularly evident in their dietary practices.

Central to their survival strategy is a diet uniquely tailored to the demands of extreme cold, scarcity of plant-based foods, and the immense caloric needs for maintaining body temperature and physical activity. This traditional diet, predominantly composed of marine mammals and fish, stands in stark contrast to global dietary guidelines, offering invaluable insights into human nutritional flexibility and physiological adaptation.

This comprehensive article delves into the fascinating world of Arctic nutrition, exploring the specific dietary choices, the physiological mechanisms that enable these populations to thrive, and the lessons we can glean from their ancestral wisdom. We will unpack the macronutrient composition, the critical role of specific nutrients, and the genetic and metabolic adaptations that define their extraordinary resilience.

The Harsh Reality of the Arctic Environment

Life above the Arctic Circle is defined by long, dark winters, temperatures plummeting far below freezing, and a land covered in snow and ice for much of the year. Agricultural practices are impossible, and terrestrial plant life is sparse and seasonal. These conditions necessitate a food acquisition strategy focused on hunting and fishing, utilizing the abundant marine and terrestrial animal resources.

The human body expends significant energy just to stay warm in such conditions. A higher basal metabolic rate (BMR) is often observed in cold-adapted populations, meaning they burn more calories at rest. This increased energy expenditure demands a diet rich in calories, primarily sourced from fat and protein.

Deconstructing the Traditional Inuit Diet

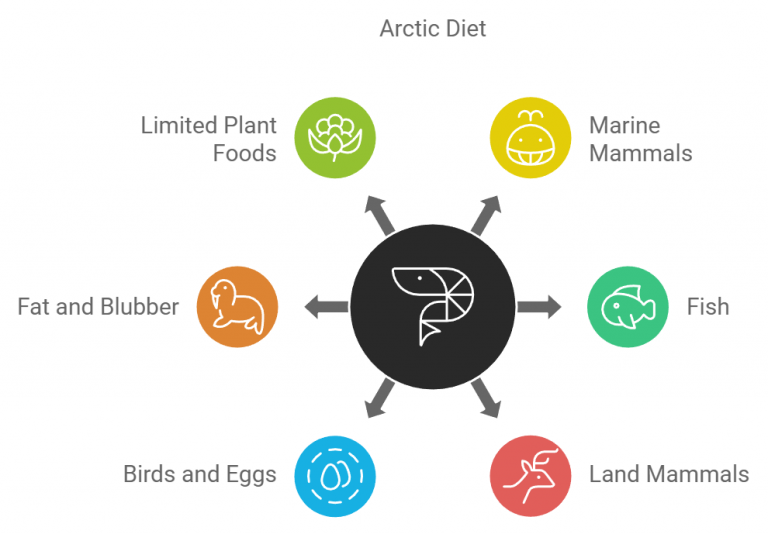

Historically, the traditional diet of the Inuit was almost exclusively animal-based, a necessity dictated by their environment. It comprised a diverse array of resources, including seals, whales (narwhal, beluga), caribou, fish (Arctic char, cod, salmon), and various birds and their eggs. Every part of the animal, from muscle meat to organs, fat, and even skin, was consumed, ensuring maximal nutrient utilization.

This ‘nose-to-tail’ approach to eating is crucial for obtaining a full spectrum of nutrients, especially in an environment where plant-based foods are scarce. The fat from marine mammals, in particular, was not just a source of calories but a vital provider of essential vitamins and fatty acids.

Macronutrient Profile: High Fat, Moderate Protein, Minimal Carbs

Unlike modern Western diets that often emphasize carbohydrates as a primary energy source, the traditional Inuit diet was remarkably high in fat, moderate in protein, and very low in carbohydrates. This macronutrient distribution is a direct adaptation to both resource availability and physiological demands.

Fat: The Arctic Superfuel. Fat, especially from marine mammals, provided the primary energy source. It is calorie-dense, offering 9 calories per gram compared to 4 calories per gram for protein and carbohydrates. This high caloric density is essential for sustaining energy levels and generating body heat in extreme cold.

Beyond energy, marine mammal fat is rich in specific types of fatty acids, notably Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid). These fats are crucial for cardiovascular health, brain function, and reducing inflammation, and they play a role in metabolic adaptation to cold.

Protein: Building Blocks and Thermogenesis. While not the primary energy source in terms of calories, protein was consumed in significant amounts, providing essential amino acids for tissue repair and maintenance. The digestion and metabolism of protein also generate a considerable amount of heat (thermogenesis), which is beneficial in a cold climate.

However, there’s a limit to how much protein the human body can efficiently metabolize without potential health issues (e.g., ‘rabbit starvation’ from lean meat alone). The high fat content of the traditional Inuit diet prevented this by providing ample non-protein energy.

Carbohydrates: A Minor Role. Carbohydrates were virtually absent from the traditional diet, limited to small amounts found in berries, roots, and some specific seaweeds gathered seasonally, or glycogen in animal muscle. This low-carb intake meant that the Inuit relied on fat for energy and entered a state of nutritional ketosis, where the body primarily burns fat for fuel, producing ketones.

Addressing Common Questions: Nutrient Acquisition Without Plants

How did they get Vitamin C? This is one of the most frequently asked questions regarding an animal-based diet. The traditional Inuit diet provided sufficient Vitamin C through fresh, uncooked or lightly cooked meat, especially organ meats like liver, brain, and adrenal glands, as well as skin (e.g., muktuk from whale skin). These parts, when consumed fresh, contain measurable amounts of Vitamin C, preventing scurvy.

What about other vitamins and minerals? The diet was incredibly nutrient-dense. Fish and marine mammals are rich sources of:

- Vitamin D: Abundant in fatty fish, seal blubber, and organ meats, crucial for bone health, especially with limited sun exposure.

- Vitamin A: Found in liver and other organ meats (caution: polar bear liver can be toxic due to extremely high levels).

- B Vitamins: Plentiful in all animal tissues, vital for energy metabolism.

- Iron: High in red meats and organs, preventing anemia.

- Calcium: Obtained from bones, fish with edible bones, and blood.

- Selenium and Zinc: Found in various animal tissues.

Physiological and Genetic Adaptations to the Diet and Cold

The long-term consumption of this unique diet, combined with generations of living in the Arctic, has likely led to specific physiological and genetic adaptations in Inuit populations. These adaptations contribute to their remarkable cold tolerance and metabolic health.

Enhanced Fat Metabolism. Studies have shown that Inuit populations possess genetic variations that influence fatty acid metabolism. These variations may enhance their ability to process and utilize unsaturated fatty acids, particularly Omega-3s, more efficiently. This could lead to a higher capacity for fat oxidation, which is crucial for energy production in a fat-rich diet.

Brown Adipose Tissue (BAT). While not exclusive to Arctic peoples, BAT plays a significant role in non-shivering thermogenesis, generating heat directly from fat. Cold exposure can activate and increase BAT activity, and some research suggests potential differences in BAT function or prevalence among cold-adapted populations.

Higher Resting Metabolic Rate. As mentioned, a higher BMR helps generate more internal heat. This can be influenced by diet composition, with a high-protein, high-fat intake potentially contributing to a sustained elevated metabolic rate.

Blood Lipids and Cardiovascular Health. Despite a diet extremely high in animal fat, traditional Inuit populations historically exhibited low rates of certain modern cardiovascular diseases. This is often attributed to the high intake of Omega-3 fatty acids, which have anti-inflammatory and triglyceride-lowering effects. However, it’s important to note that modern dietary shifts have altered these health profiles.

Modern Dietary Shifts and Health Implications

In recent decades, the traditional Inuit diet has undergone significant changes due to increased access to Western processed foods. Store-bought items high in sugar, refined carbohydrates, and unhealthy fats have largely replaced traditional foods, leading to a rise in ‘nutrition transition’ diseases.

These include higher rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, mirroring trends seen in other indigenous communities globally. This stark contrast highlights the importance of traditional dietary practices and the potential health risks associated with abandoning them for a Westernized diet.

Efforts are now being made to revitalize traditional food systems, recognizing their cultural significance and immense health benefits. Promoting access to traditional foods and educating younger generations about their nutritional value is crucial for improving health outcomes.

Lessons from the Arctic Diet for Modern Nutrition

- The Power of Nutrient Density: Emphasizes consuming whole, unprocessed foods that are rich in essential vitamins, minerals, and healthy fats.

- Importance of Omega-3s: Reinforces the critical role of marine-sourced Omega-3 fatty acids for overall health, particularly cardiovascular and brain health.

- Flexibility of Human Metabolism: Demonstrates the human body’s remarkable ability to adapt and thrive on diverse macronutrient ratios, including very low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets.

- Holistic Food Systems: Highlights the value of ‘nose-to-tail’ eating, reducing waste, and maximizing nutrient intake from animal sources.

- Impact of Food Environment: Underscores how dramatically our environment and food choices shape our health and susceptibility to chronic diseases.

The traditional Inuit diet is not just a historical curiosity; it is a living testament to human adaptability and the intricate relationship between diet, environment, and health. It challenges many conventional nutritional paradigms and offers a compelling case for the nuanced understanding of human dietary needs.

By studying these remarkable adaptations, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diverse paths human societies have taken to nourish themselves and thrive in the face of nature’s greatest challenges. The wisdom embedded in Arctic traditional foods continues to resonate, offering guidance for sustainable living and optimal health in any climate.

In conclusion, the ‘Eskimo diet’ (more accurately, the traditional Inuit diet) is a masterclass in cold climate adaptation. It’s a high-fat, moderate-protein, virtually carb-free regimen, rich in marine-derived Omega-3s, fat-soluble vitamins, and essential minerals. This diet, coupled with unique physiological and potentially genetic adaptations, enabled Arctic populations to generate heat, sustain energy, and acquire all necessary nutrients without significant plant consumption.

Their historical health outcomes, distinct from modern diet-related illnesses, underscore the profound connection between traditional food systems and well-being. The Inuit diet stands as a powerful example of human metabolic flexibility and the ingenious ways societies have adapted to thrive in the most extreme corners of our planet.