The vast and often unforgiving landscapes of the Arctic are home to some of the world’s most resilient and iconic wildlife. For centuries, the Indigenous peoples of this region, including the Inuit, Yupik, and other northern communities (historically and sometimes broadly referred to as ‘Eskimo’ peoples), have lived in harmony with these animals, relying on them for sustenance, culture, and survival.

Understanding the dynamics of animal populations in these extreme environments is not merely an academic exercise; it is fundamental to conservation, wildlife management, and the preservation of Indigenous ways of life. These studies offer crucial insights into the health of the Arctic ecosystem and serve as vital indicators of global environmental change.

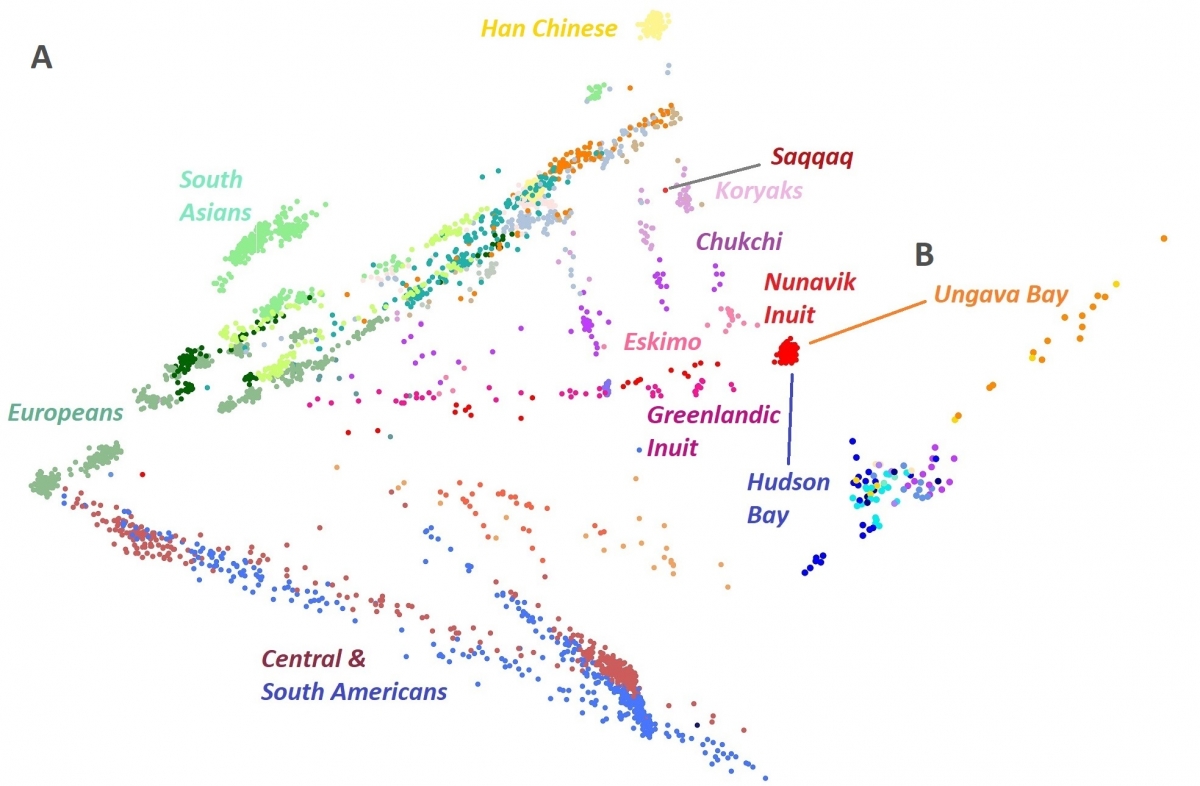

While the term ‘Eskimo’ has been historically used, it’s important to acknowledge that many Indigenous Arctic peoples prefer to be identified by their specific group names, such as Inuit in Canada and Greenland, and Yupik in Alaska and Siberia. This article will focus on the collective efforts and knowledge systems of these diverse Indigenous groups in understanding and managing Arctic wildlife populations.

The Critical Importance of Arctic Wildlife Studies

Arctic animal population studies are paramount for several reasons. They help scientists and communities track species health, identify threats, and inform conservation strategies. The Arctic is experiencing environmental changes at an accelerated rate, making these studies more urgent than ever.

Furthermore, these investigations are deeply intertwined with the cultural heritage and food security of Indigenous communities. Many Arctic animals are central to subsistence hunting, providing essential nutrition and forming the bedrock of traditional economies and spiritual practices.

Key Species Under the Arctic Lens

A wide array of species are the focus of these comprehensive studies, each playing a unique role in the delicate Arctic food web. Understanding their numbers, distribution, and health is vital.

Polar Bears: Sentinels of the Sea Ice

Perhaps the most iconic Arctic predator, polar bears (Ursus maritimus) are a primary subject of population studies. Their reliance on sea ice for hunting seals makes them particularly vulnerable to climate change. Scientists and Indigenous hunters closely monitor their numbers, denning sites, and movements across their vast range.

Studies on polar bear populations often involve aerial surveys, mark-recapture techniques (tagging and tracking), and increasingly, genetic sampling. Traditional knowledge shared by Inuit hunters provides invaluable context on local bear behaviors and population trends that scientific methods alone might miss.

Caribou and Reindeer: The Migratory Herds

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in North America and reindeer in Eurasia are fundamental to the terrestrial Arctic ecosystem and Indigenous cultures. These migratory herbivores undertake epic journeys, and their population fluctuations have profound impacts on both predators and human communities.

Monitoring caribou herds involves extensive aerial surveys to count animals, track migration routes, and assess calving success. Habitat changes, disease, and human activity are all factors meticulously studied to understand population dynamics and inform sustainable harvesting quotas.

Marine Mammals: Seals and Whales

Arctic waters teem with marine life, including various seal species (ringed, bearded, harp, spotted) and majestic whales (bowhead, narwhal, beluga). These animals are crucial food sources and hold deep cultural significance for coastal Indigenous communities.

Population studies for marine mammals often employ acoustic monitoring, satellite tagging, and aerial or boat-based surveys. For species like the bowhead whale, which holds immense cultural value, Indigenous co-management plays a pivotal role in ensuring sustainable harvests and monitoring population recovery.

Other Arctic Wildlife: From Foxes to Fish

Beyond the ‘big three,’ studies also encompass arctic foxes, arctic hares, muskoxen, various bird species, and fish populations (e.g., Arctic char). Each contributes to the overall biodiversity and health of the northern ecosystems. Changes in their numbers can signal broader ecological shifts.

Bridging Knowledge Systems: Traditional and Scientific Methods

Effective Arctic animal population studies increasingly recognize the power of integrating two distinct yet complementary knowledge systems: Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Western science.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)

Indigenous communities possess generations of accumulated knowledge about the land, sea, and animals. TEK provides long-term perspectives on animal behavior, migration patterns, and environmental changes that often predate modern scientific records. This knowledge is crucial for understanding baseline conditions and nuanced ecological relationships.

Indigenous hunters, elders, and community members contribute vital observations, historical data, and contextual understanding that enriches scientific findings. This collaborative approach ensures that research is culturally relevant and addresses local concerns.

Modern Scientific Methodologies

- Satellite Telemetry: GPS collars and tags provide real-time data on animal movements, habitat use, and migration routes.

- Aerial and Ground Surveys: Used for counting animals, identifying denning sites, and assessing herd health over vast areas.

- Genetic Analysis: DNA samples help determine population structure, genetic diversity, and relatedness, crucial for conservation.

- Remote Sensing: Satellite imagery tracks sea ice extent, vegetation changes, and other habitat alterations.

- Acoustic Monitoring: Underwater microphones detect marine mammal vocalizations, helping to track their presence and movements.

- Camera Traps: Automated cameras capture images and videos of elusive species in remote locations.

Challenges in Arctic Research and Conservation

Conducting animal population studies in the Arctic presents unique and formidable challenges.

The sheer vastness and remoteness of the Arctic make fieldwork logistically complex and incredibly expensive. Harsh weather conditions, including extreme cold, blizzards, and limited daylight in winter, pose significant safety risks and operational difficulties.

Climate change itself is the overarching challenge. Rapid warming leads to unpredictable ice conditions, altered prey availability, and shifting habitats, complicating long-term data collection and trend analysis.

International cooperation is often required as many species, like polar bears and migratory birds, cross national borders. Harmonizing research methodologies and conservation policies across different jurisdictions can be complex.

The Unmistakable Impact of Climate Change

The Arctic is warming at more than twice the global average, leading to profound effects on animal populations. These changes are a central theme in virtually all Arctic wildlife studies.

Sea Ice Loss: For species like polar bears, ringed seals, and narwhals, diminishing and thinner sea ice directly impacts hunting grounds, breeding habitats, and migration corridors. This leads to increased energetic demands and reduced reproductive success.

Changes in Food Webs: Alterations in ocean temperatures and currents affect phytoplankton and zooplankton, cascading up the food chain to fish, seals, and whales. Terrestrial changes impact vegetation vital for caribou and other herbivores.

Permafrost Thaw: Thawing permafrost can disrupt denning sites, alter drainage patterns, and release ancient pathogens, posing new threats to wildlife.

Increased Human Activity: As ice recedes, new shipping routes, resource extraction projects, and tourism opportunities emerge, leading to potential increases in human-wildlife conflict and habitat disturbance.

The Indispensable Role of Indigenous Stewardship

Indigenous communities are not just observers of these changes; they are active stewards of the land and sea. Their involvement is critical for effective conservation and management.

Co-management Boards: Many regions have established co-management bodies where Indigenous and government representatives work together to set hunting quotas, develop conservation plans, and conduct research. This ensures that traditional practices and scientific findings are equally valued.

Community-Based Monitoring: Local communities are often on the front lines of data collection, providing consistent, on-the-ground observations that complement large-scale scientific surveys. This empowers communities and builds local capacity.

Advocacy and Policy Influence: Indigenous organizations play a crucial role in advocating for stronger environmental protections and ensuring that policy decisions reflect the unique needs and perspectives of Arctic residents.

Future Directions and Hope for the Arctic

The future of Arctic animal populations hinges on continued, collaborative efforts. Integrated approaches that weave together TEK and cutting-edge science are essential for developing robust conservation strategies.

Investment in long-term monitoring programs, technological advancements in tracking, and sustained funding for research are vital. Perhaps most importantly, fostering genuine partnerships with Indigenous communities will ensure that conservation efforts are effective, equitable, and sustainable.

Ultimately, the health of Arctic animal populations is a mirror reflecting the health of our planet. The studies conducted by scientists and Indigenous peoples in these remote northern regions provide not just data, but a profound call to action for global environmental stewardship.

In conclusion, ‘Eskimo animal population studies’ – more accurately described as Indigenous Arctic animal population studies – are a critical field combining traditional wisdom and modern science. They offer indispensable insights into the status of iconic species like polar bears, caribou, and marine mammals, highlighting the severe impacts of climate change and the vital role of Indigenous communities in conservation. These ongoing efforts are crucial for safeguarding the unique biodiversity of the Arctic and ensuring a sustainable future for its people and wildlife.