Echoes in Earth: Unearthing the Mysteries of Early Woodland Mound Builders

Long before European settlers charted the rivers and valleys of eastern North America, a profound transformation was underway. From approximately 1000 BCE to 1 CE, a complex and enduring cultural phenomenon emerged, leaving behind an indelible mark on the landscape: the Early Woodland Period mound builders. These ancient societies, primarily known through the Adena culture, shifted from purely nomadic existences to more settled lives, culminating in the construction of monumental earthworks that continue to captivate archaeologists and the public alike. Far from mere piles of dirt, these mounds were profound statements of spirituality, social organization, and a deep connection to the land and the cosmos, serving as silent testaments to an ingenious and enigmatic past.

The Early Woodland Period marks a critical juncture in the prehistory of Eastern North America. Following the Archaic Period, which was characterized by highly mobile hunter-gatherer groups, the Early Woodland saw significant innovations that facilitated a more sedentary lifestyle. The widespread adoption of pottery, initially simple and utilitarian, allowed for more efficient food storage and cooking. Simultaneously, the intentional cultivation of native plants like squash, gourds, sunflower, sumpweed, and chenopod began to supplement traditional foraging, creating a more stable food supply. This growing sedentism was a prerequisite for the ambitious undertaking of mound construction, as it required a sustained, concentrated labor force.

Geographically, the Early Woodland mound building cultures flourished across a vast expanse, from the Great Lakes region south to the Gulf Coast and from the Mississippi River east to the Atlantic seaboard. However, the Ohio River Valley and its tributaries stand out as a heartland for this phenomenon, particularly for the Adena culture. The Adena, named after Thomas Worthington’s estate in Chillicothe, Ohio, where one of the first excavated mounds was located, represent the quintessential Early Woodland mound builders. Their influence radiated across present-day Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, and parts of Pennsylvania and Maryland.

The Earthworks: Engineering and Purpose

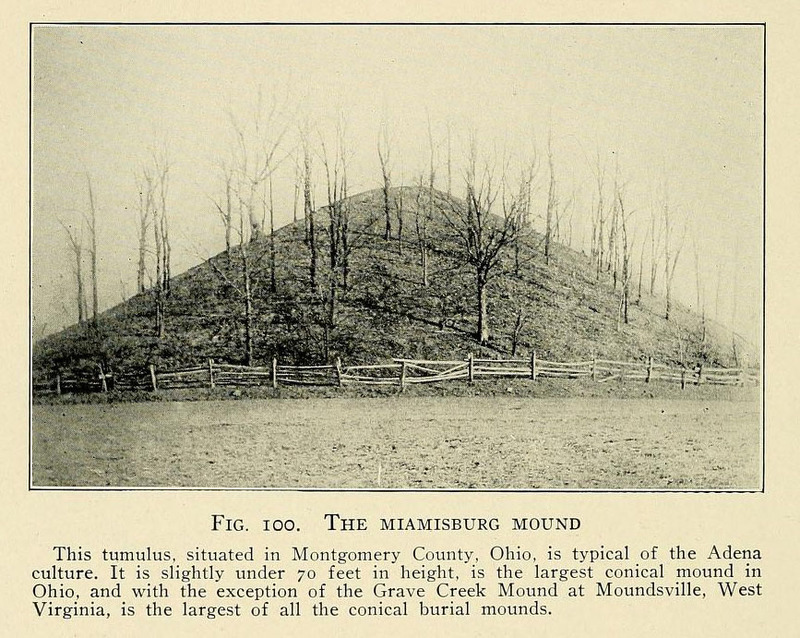

The most striking legacy of the Early Woodland people are their earthworks. Unlike the later, more geometrically precise earthworks of the Middle Woodland Hopewell culture, Early Woodland mounds, particularly those of the Adena, are predominantly conical in shape. These often impressive, dome-like structures range widely in size, from small, barely perceptible rises to massive hills dominating the landscape. The Grave Creek Mound in Moundsville, West Virginia, stands as one of the largest, reaching nearly 70 feet (21 meters) high and 240 feet (73 meters) in diameter at its base. Similarly, the Miamisburg Mound in Ohio, though slightly smaller, remains a testament to immense communal effort.

The construction of these mounds was a monumental undertaking, involving countless hours of labor with rudimentary tools. Earth was dug from nearby borrow pits using stone hoes, shell scrapers, and wooden shovels, then transported to the construction site in baskets or hide containers. Layer upon layer, earth was meticulously piled, often incorporating different colored soils to create a visually striking effect or possibly to mark different stages of construction or ritual significance. This was no mere casual endeavor; it required organized leadership, a shared vision, and sustained communal effort over extended periods, sometimes spanning generations.

"The sheer scale of these earthworks, built without modern machinery, speaks volumes about the social cohesion and collective purpose of Early Woodland communities," notes Dr. Bretton Giles, an archaeologist specializing in Eastern Woodlands prehistory. "They represent not just engineering feats, but profound expressions of a people’s worldview and their relationship with the sacred."

The primary function of these conical mounds was as burial sites. Unlike later cultures that often created separate cemeteries, Early Woodland mounds frequently served as elaborate crypts for the dead, particularly for individuals of high status or importance. The burial process itself was often complex and multi-staged. Individuals might be interred in log tombs, sometimes after being cremated, or placed in flexed positions directly within the earth. Grave goods, varying significantly in quantity and type, were frequently interred with the deceased. These artifacts offer invaluable insights into the social hierarchy, spiritual beliefs, and material culture of the period.

Artifacts and Social Complexity

The artifacts recovered from Early Woodland mounds and associated sites paint a vivid picture of a developing society. Pottery, while initially crude, evolved to include more varied forms and decorative elements, typically cord-marked or fabric-impressed. Stone tools like projectile points (often of the Adena type, characterized by a straight stem and broad blades) and celts were common. However, it is the more elaborate and exotic artifacts that truly highlight the emerging social complexity and extensive trade networks of the time.

Perhaps the most distinctive Adena artifact is the tubular pipe. Carved from fine-grained stone like pipestone or steatite, these pipes often feature human or animal effigies, such as the famous "Adena Pipe" depicting a human figure wearing an elaborate ear spool. These pipes were likely used in ceremonial contexts, perhaps for smoking tobacco or other plant materials, facilitating communication with the spirit world. Their intricate craftsmanship suggests they were prestige items, perhaps controlled by shamans or community leaders.

Other significant grave goods include gorgets (ornamental pendants worn around the neck), often made of slate or shell, and intricate stone tablets engraved with zoomorphic or anthropomorphic designs. Copper ornaments, sourced from the Great Lakes region, and mica cutouts, from the Appalachian Mountains, demonstrate extensive long-distance trade networks. These exotic materials, brought from hundreds of miles away, were not simply utilitarian but served as symbols of status, power, and connection to a broader, interconnected world. The presence of such items in specific burials suggests a nascent social stratification, where certain individuals or lineages held privileged positions within the community.

Spiritual Worldview and Community Life

The construction of burial mounds was intrinsically linked to the spiritual worldview of the Early Woodland people. These earthworks were more than just graves; they were sacred spaces, focal points for communal ritual, and perhaps even cosmological maps. The act of building a mound could have reinforced community bonds, created a shared identity, and served as a tangible link between the living and their ancestors. The mounds likely functioned as places of ancestor veneration, where the spirits of the dead were believed to reside and exert influence over the living.

Archaeologist Dr. Brian Fagan notes in his work on ancient North America that "the Adena people were profoundly spiritual, and their mounds were not merely tombs but expressions of a complex cosmology that integrated the living, the dead, and the natural world." The placement of grave goods, the orientation of burials, and the very act of constructing these enduring monuments all point to a rich spiritual life centered around death, rebirth, and the cyclical nature of existence.

Beyond the spiritual, mound building also reflects a significant level of social organization. The ability to mobilize and coordinate hundreds, if not thousands, of individuals for a single project indicates the presence of some form of leadership, whether charismatic chiefs, respected elders, or a council that could command and motivate labor. The effort involved would have been substantial, likely requiring seasonal gatherings where communities converged to participate in construction, exchange goods, and engage in shared ceremonies. These gatherings would have further cemented social ties and reinforced a shared cultural identity.

Legacy and Enduring Questions

The Early Woodland Period mound builders, particularly the Adena, laid the foundational elements for the even more elaborate and geographically widespread Middle Woodland Hopewell culture that followed. Many of the ceremonial practices, trade networks, and social structures pioneered by the Adena were adopted and expanded upon by the Hopewell, leading to even larger and more complex earthworks. However, the Early Woodland cultures stand on their own as a period of profound innovation and cultural flourishing.

Despite extensive archaeological investigation, many questions about the Early Woodland mound builders remain unanswered. What were their exact religious beliefs? How did their social structures function on a daily basis? What were the specific political dynamics that governed their communities? The lack of written records means that archaeologists must meticulously piece together their understanding from the material remains, a challenging but endlessly rewarding endeavor.

Today, the mounds of the Early Woodland Period stand as silent, enduring monuments across the Eastern Woodlands. They are not merely archaeological sites but powerful cultural landscapes that connect us to a deep and sophisticated past. They remind us that complex societies, profound spiritualities, and monumental architectural achievements were flourishing in North America long before recorded history, leaving behind a legacy of earth and mystery that continues to speak across millennia. These echoes in earth challenge us to look beyond the visible, to imagine the vibrant communities that once thrived here, and to appreciate the rich tapestry of human history woven into the very ground beneath our feet.