The Forging of a Nation, The Fading of a Culture: Early Attempts at Native American Assimilation

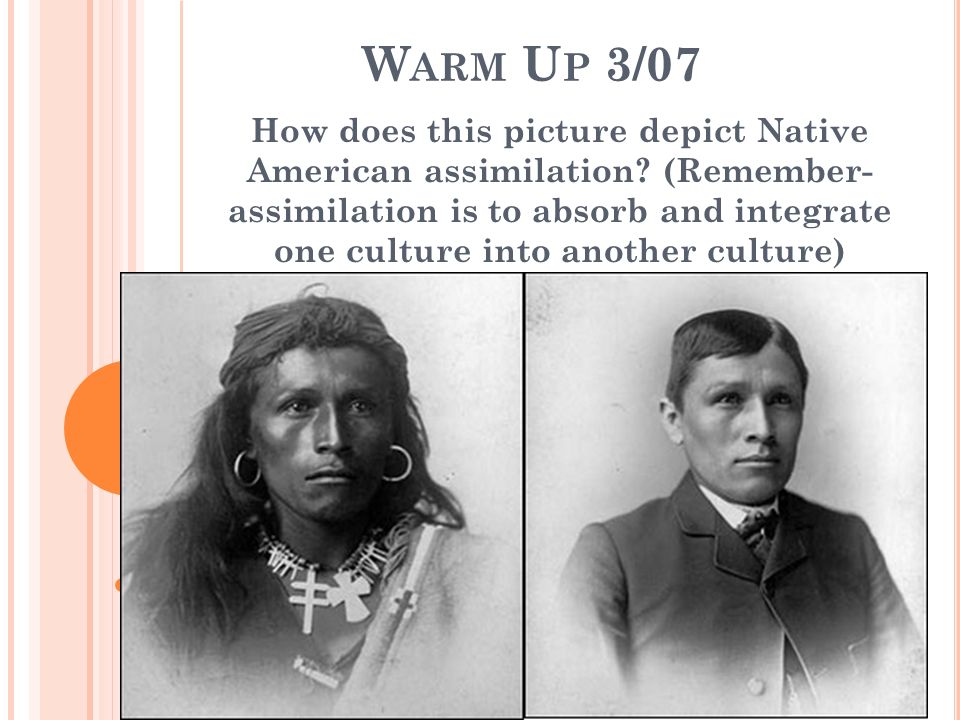

From the earliest colonial encounters on the shores of a continent teeming with diverse Indigenous nations, a powerful and persistent ideology began to take root among European settlers: the belief that Native American cultures were inherently inferior and, therefore, must be "civilized." This conviction, deeply intertwined with religious fervor, economic ambition, and a burgeoning sense of national destiny, fueled centuries of systematic efforts to assimilate Indigenous peoples into the dominant Euro-American society. These early attempts, often cloaked in the language of benevolence and progress, laid the groundwork for policies that would profoundly and tragically reshape the Native American experience, leaving an indelible scar on the nation’s history.

The narrative of assimilation is not monolithic; it evolved over time, adapting to changing political landscapes, intellectual currents, and the ever-present hunger for land. Yet, its core tenets remained remarkably consistent: replace Indigenous languages with English, communal land ownership with private property, traditional spiritual beliefs with Christianity, and subsistence economies with settled agriculture.

Colonial Crossroads: Saving Souls and Securing Land (17th-18th Centuries)

The initial phase of assimilation efforts can be traced back to the colonial period, driven largely by missionary zeal. Puritan leaders in New England, for instance, saw it as their divine duty to convert the "heathen" natives. John Eliot, a prominent Puritan minister, spearheaded the creation of "Praying Towns" in the mid-17th century, such as Natick, Massachusetts. In these settlements, Native Americans were encouraged to adopt English customs, language, dress, and agricultural practices, and, crucially, to embrace Christianity.

These "Praying Towns," while ostensibly designed for the spiritual and material upliftment of Native peoples, also served a pragmatic purpose for the colonists. They created a buffer between English settlements and unconverted tribes, and facilitated the acquisition of Native lands. The very act of "civilizing" was often seen as a prerequisite for rightful land ownership, as Europeans frequently argued that Indigenous peoples, by not farming or enclosing land, were not making "proper" use of it.

The establishment of institutions like the Harvard Indian College in 1655 further exemplified this early assimilationist impulse. Though few Native students ultimately graduated, its existence underscored the colonial ambition to educate and integrate Indigenous individuals into the dominant culture, thereby, it was hoped, facilitating the conversion and pacification of their communities. Yet, even in these early stages, the inherent conflict was clear: were Native people being integrated as equals, or merely as a means to an end for colonial expansion? The answer, tragically, often leaned towards the latter.

The Early Republic: "Civilization" as a National Policy (Late 18th – Early 19th Centuries)

Following the American Revolution, the young United States inherited and expanded upon these assimilationist policies. The newly formed nation, grappling with westward expansion and the presence of powerful Native American confederacies, sought to establish a more coherent strategy than the piecemeal efforts of the colonies. President George Washington and his Secretary of War, Henry Knox, articulated a policy that became known as the "civilization program."

Knox, in a 1789 report to Washington, acknowledged past injustices but proposed a path forward rooted in assimilation: "It would be an operation of a most arduous nature to attempt to destroy utterly the Indians… It is however presumed, that the independence of the United States considered, that the said Indians shall be led to a greater degree of civilization, and to become good citizens of the United States." The goal was clear: transform Native Americans into yeoman farmers, making them self-sufficient by American standards, and thereby reducing their land needs and their perceived threat to national security.

This policy was enthusiastically embraced by figures like President Thomas Jefferson. While often portrayed as an advocate for Native Americans, Jefferson’s vision was deeply rooted in assimilation. He believed that if Native peoples adopted American agricultural practices and embraced private land ownership, they would require less land, thus freeing up vast territories for white settlement. In an 1803 letter to William Henry Harrison, then Governor of the Indiana Territory, Jefferson laid out his strategy: "We shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop them off by a cession of lands." The cynical underbelly of "civilization" was thus exposed: a tool for land acquisition.

The "Five Civilized Tribes" and the Betrayal of Progress

Perhaps no group exemplifies the paradox and ultimate tragedy of this early assimilation policy more vividly than the "Five Civilized Tribes" of the Southeast: the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole. These nations, in a remarkable and often heartbreaking attempt to coexist, actively adopted many aspects of Euro-American culture.

The Cherokee Nation, in particular, made extraordinary strides. They developed a written language and syllabary under the leadership of Sequoyah in 1821, leading to widespread literacy and the publication of their own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. They established a republican form of government with a written constitution, built schools, adopted farming techniques, owned plantations, and even held enslaved African Americans – practices directly reflective of their white neighbors. They were, by all outward measures, "civilized" according to the standards set by the U.S. government.

Yet, their embrace of American customs did not secure their place. Their lands in Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee were coveted for cotton cultivation and, later, for the discovery of gold. Despite their adherence to treaties and their demonstrable "progress," the pressure for their removal intensified. This culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, which authorized the forced relocation of these tribes to lands west of the Mississippi River.

Jackson, in his 1830 message to Congress, presented removal as a benevolent act, an opportunity for Native Americans to "pursue their own happiness in their own way." He famously defied the Supreme Court’s ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which affirmed Cherokee sovereignty. His alleged quote, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it," encapsulates the executive branch’s disregard for legal protections. The resulting forced march, known as the Trail of Tears, saw thousands of Cherokee men, women, and children perish from disease, starvation, and exposure. It stands as a stark and horrific testament to the ultimate failure of assimilation as a path to peaceful coexistence when land greed and racial prejudice prevailed.

Underlying Motivations and Enduring Legacy

The early attempts at Native American assimilation were rarely driven by pure altruism. They were complex endeavors fueled by a mix of genuine, if ethnocentric, belief in the superiority of European culture, coupled with powerful economic and political imperatives. The concept of Manifest Destiny, the conviction that American expansion across the continent was divinely ordained, provided a moral veneer for territorial conquest. Assimilation was often seen as the only "humane" alternative to outright extermination, a way to resolve the "Indian problem" without the stain of genocide, while simultaneously freeing up valuable land.

Moreover, the policies were deeply rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding, or deliberate misrepresentation, of Native American societies. European settlers struggled to comprehend or accept communal land ownership, diverse spiritual practices, and non-hierarchical governance structures. These differences were frequently interpreted as signs of savagery, backwardness, or lack of intelligence, reinforcing the perceived need for "civilization."

The legacy of these early assimilation efforts is profound and enduring. They initiated a cycle of cultural trauma, loss of language, disruption of traditional social structures, and profound distrust between Native nations and the U.S. government. While the more formalized and aggressive policies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries – particularly the boarding school era and the Dawes Act – would further intensify these impacts, the seeds of cultural destruction and land dispossession were sown much earlier.

Today, Native American communities continue to grapple with the historical wounds inflicted by these policies. The struggle for cultural revitalization, linguistic preservation, and self-determination is a direct response to centuries of forced assimilation. The early attempts to "civilize" Native Americans, while presented as a path to progress, ultimately reveal a darker truth: a nation’s expansion built, in part, on the deliberate suppression and attempted erasure of the cultures that predated its very existence. Understanding this painful chapter is not just about recounting history, but about acknowledging its ongoing resonance and the continuing fight for justice and recognition.