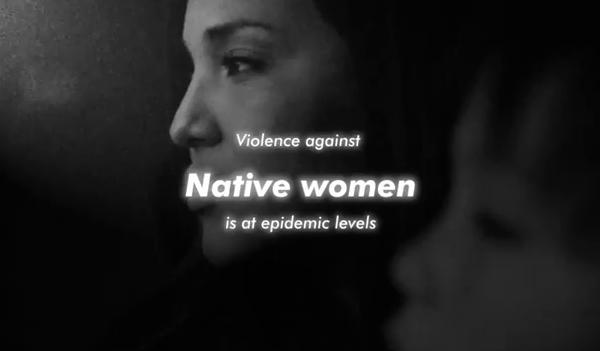

Shattered Sanctuaries: The Silent Epidemic of Domestic Violence on Native American Reservations

In the vast, often remote landscapes of Native American reservations, a crisis of devastating proportions unfolds, largely hidden from mainstream view. Domestic violence, a scourge that plagues societies worldwide, manifests with particularly brutal intensity and alarming frequency within Indigenous communities, shattering families, eroding cultural heritage, and claiming lives. The statistics paint a stark picture of a silent epidemic, where historical trauma, jurisdictional complexities, and systemic neglect converge to create an environment where Native women disproportionately bear the brunt of intimate partner violence.

The numbers are not merely statistics; they represent generations of pain, resilience, and an urgent call for justice. A landmark 2016 study by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) revealed that more than four out of five (84.3%) Native American and Alaska Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime. This figure is profoundly higher than that for other demographics. More specifically, 56.1% have experienced sexual violence, and a staggering 55.5% have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner. These aren’t just minor altercations; these are often severe, life-altering acts of violence that leave deep physical and psychological scars.

To put this into perspective, Native women are at a significantly higher risk of experiencing domestic violence, sexual assault, and murder compared to women of other ethnicities. While national averages for intimate partner violence are already concerning, the rates within Indigenous communities are often double or even triple, highlighting a systemic failure to protect and support these vulnerable populations.

The Deep Roots of a Crisis: Historical Trauma and Systemic Dispossession

Understanding the disproportionate rates of domestic violence on reservations requires an examination of the deep-seated historical trauma that continues to reverberate through Indigenous communities. Centuries of colonization, forced assimilation, land dispossession, and the systematic dismantling of traditional societal structures have created a legacy of intergenerational trauma that fuels many of the social ills seen today.

The boarding school era, for instance, forcibly removed Native children from their families and cultures, subjecting them to physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and stripping them of their language and spiritual practices. This brutal process not only severed family bonds but also disrupted traditional gender roles and community support systems that once protected women and children. Prior to colonization, many Indigenous societies were matriarchal or had strong, respected roles for women, which were systematically undermined by patriarchal colonial systems.

Today, these historical wounds manifest in myriad ways, including high rates of poverty, substance abuse, mental health issues, and a breakdown of traditional family units. These factors, while not excusing violent behavior, create a fertile ground for domestic violence to take root and fester. The cycle of trauma is often passed down, contributing to a perpetuation of violence within families and communities.

The Jurisdictional Maze: A Legal Labyrinth for Justice

Perhaps one of the most critical and complex factors exacerbating domestic violence on reservations is the convoluted and often confusing jurisdictional framework that governs tribal lands. For decades, a legal patchwork created by federal laws and Supreme Court rulings has left a significant gap in the ability of tribal governments to prosecute non-Native offenders.

The landmark 1978 Supreme Court case Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe stripped tribal courts of criminal jurisdiction over non-Native individuals, even when crimes were committed on tribal land. This created a perilous loophole: if a non-Native perpetrator committed domestic violence against a Native woman on a reservation, tribal authorities could not prosecute them. Federal authorities, often under-resourced and geographically distant, frequently declined to prosecute these cases, citing a lack of resources or prioritizing more "serious" crimes. This left victims with virtually no recourse, allowing perpetrators to act with impunity.

"For too long, the jurisdictional maze has been a shield for perpetrators and a barrier to justice for our women," states Sarah Deer, a Muscogee (Creek) Nation citizen and leading scholar on tribal law. "It essentially created zones of impunity where non-Native men could abuse Native women without fear of prosecution, directly contributing to the epidemic."

Recognizing this egregious injustice, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) Reauthorization of 2013 was a critical step forward. It partially restored tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Native perpetrators of domestic violence, dating violence, and protective order violations committed against Native victims on tribal lands. This allowed tribal courts to hold non-Native offenders accountable, a significant victory for tribal sovereignty and victim safety.

However, the 2013 VAWA reauthorization still left gaps. It didn’t cover crimes like sexual assault, stalking, or child abuse committed by non-Natives, nor did it extend to non-Native perpetrators who lacked sufficient ties to the reservation. The subsequent VAWA Reauthorization of 2022 further expanded tribal jurisdiction, allowing tribes to prosecute non-Native offenders for sexual assault, stalking, child abuse, and human trafficking committed on tribal lands. While a monumental achievement, the implementation remains challenging, requiring significant resources, training, and coordination between tribal, federal, and state agencies.

Lack of Resources: A Dire Shortage of Safe Harbors

Beyond the legal complexities, reservations often face a severe lack of basic resources essential for addressing domestic violence. Many tribal communities are rural and isolated, with vast distances between homes and services. This geographical challenge is compounded by:

- Limited Law Enforcement: Tribal police forces are often understaffed, underfunded, and lack the necessary training and equipment to respond effectively to domestic violence calls, especially in remote areas. Response times can be hours, not minutes.

- Few Shelters and Safe Houses: The scarcity of domestic violence shelters on or near reservations means victims often have nowhere safe to go. Leaving an abusive situation is incredibly difficult when the nearest shelter is hundreds of miles away, and culturally appropriate services are even rarer.

- Insufficient Healthcare and Mental Health Services: Access to medical care for injuries, forensic exams for sexual assault, and mental health counseling for trauma is severely limited. This perpetuates cycles of unaddressed trauma and prevents victims from healing.

- Lack of Culturally Competent Support: Mainstream services often fail to understand or respect Indigenous cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and the unique historical context of Native American communities. This can alienate victims and make them hesitant to seek help.

These resource deficits mean that many Native women experiencing violence are trapped, with few avenues for escape or support. The choice often becomes staying in an abusive situation or leaving their homes, families, and communities with nowhere to go.

The Connection to MMIW/P: A Broader Crisis

Domestic violence is inextricably linked to the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People (MMIW/P). Many cases of missing or murdered Indigenous women begin with a history of domestic violence. Perpetrators often use violence and control as a means of isolating victims, making them more vulnerable to further harm, including abduction and murder.

A 2018 report by the Urban Indian Health Institute found that out of 5,712 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in 2016, only 116 were logged in the Department of Justice database. This stark discrepancy highlights the severe underreporting and lack of attention given to these cases by federal authorities, further demonstrating how Indigenous women fall through the cracks of the justice system. The MMIW/P movement has brought crucial attention to the systemic violence against Indigenous people, with domestic violence at its core.

Voices of Resilience and the Path Forward

Despite the overwhelming challenges, Indigenous communities are not passively accepting this crisis. Tribal leaders, advocates, and grassroots organizations are tirelessly working to reclaim traditional values of respect and community, build their own support systems, and advocate for policy changes.

Many tribes are developing culturally specific programs that incorporate traditional healing practices, elder guidance, and community-led initiatives to address violence. They are creating safe spaces, advocating for increased funding, and collaborating with federal and state partners to navigate the complex jurisdictional landscape. The focus is not just on punitive justice but on holistic healing for individuals, families, and communities.

The path forward requires a multi-pronged approach:

- Sustained and Increased Funding: Robust federal funding is crucial for tribal law enforcement, victim services, shelters, and culturally competent mental health care.

- Full Implementation of VAWA: Ensuring that tribal courts have the resources and support to fully exercise their expanded jurisdiction under VAWA 2013 and 2022 is paramount.

- Improved Data Collection: Accurate and comprehensive data is essential to understand the true scope of the problem and allocate resources effectively. Federal agencies must work with tribes to improve reporting and tracking.

- Enhanced Collaboration: Greater cooperation between tribal, federal, and state law enforcement and judicial systems is needed to ensure seamless responses to violence and prevent perpetrators from exploiting jurisdictional gaps.

- Addressing Historical Trauma: Long-term investment in community-led initiatives that address the root causes of violence, including historical trauma, poverty, and substance abuse, is vital for lasting change.

- Cultural Revitalization: Supporting efforts to revitalize traditional cultural practices and matriarchal values can strengthen community bonds and empower Indigenous women.

The statistics of domestic violence on Native American reservations are not just numbers; they are a testament to systemic failures, historical injustices, and an urgent humanitarian crisis. Addressing this epidemic requires not only legal reform and increased resources but also a profound commitment to understanding and respecting the sovereignty, culture, and resilience of Indigenous peoples. Only then can these shattered sanctuaries begin to heal, and justice finally reach those who have been marginalized for far too long.