The Invisible Plague: Diseases Decimating Turtle Populations Across Turtle Island

From the ancient shores of the Atlantic to the vast plains and the rugged Pacific coast, Turtle Island – the ancestral name for North America – faces a silent, insidious crisis. Its venerable inhabitants, the turtles, creatures of immense spiritual significance and ecological importance, are under siege not just from habitat loss and climate change, but from a growing array of diseases that are decimating populations with alarming speed and efficiency. This invisible plague, often exacerbated by human-induced environmental degradation, poses a profound threat to species already teetering on the brink, and underscores the delicate interconnectedness of all life on this continent.

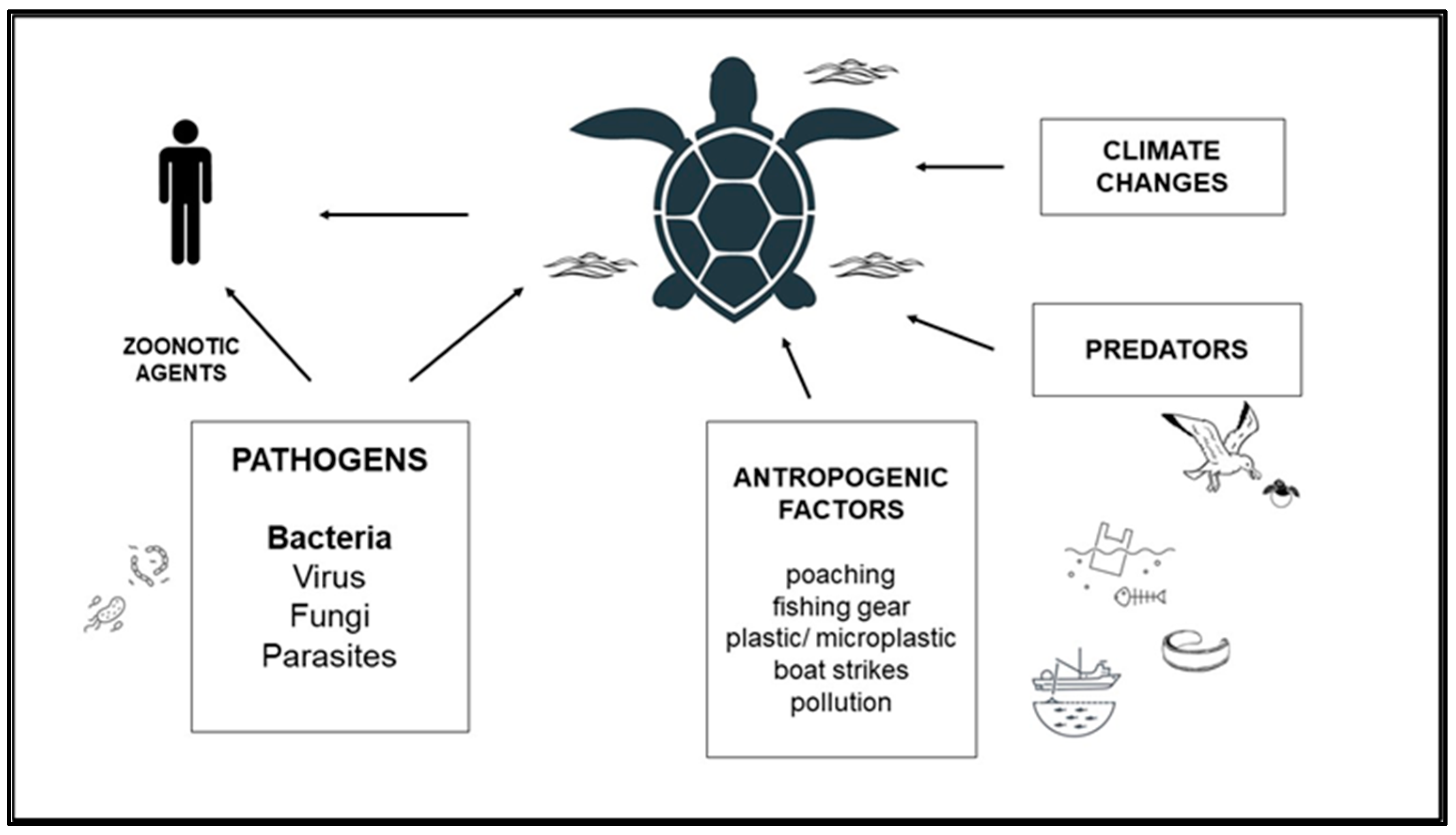

For many Indigenous peoples, the turtle is a foundational figure, a symbol of life, perseverance, and the very land upon which we stand. The health of these ancient reptiles is therefore a barometer for the health of the entire ecosystem. Unfortunately, that barometer is currently signaling a deep malaise. Across marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments, researchers and conservationists are grappling with outbreaks of viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites, often emerging or intensifying due to a confluence of factors that stress turtle immune systems and facilitate pathogen spread.

Fibropapillomatosis: The Sea Turtle’s Scourge

Perhaps one of the most visually striking and devastating diseases affecting marine turtles is Fibropapillomatosis (FP). Characterized by the growth of debilitating, cauliflower-like tumors on the skin, eyes, mouth, and internal organs, FP is caused by a chelonid herpesvirus. While FP has been observed globally, its prevalence in green sea turtles (and to a lesser extent, loggerheads and olive ridleys) in certain regions of Turtle Island, particularly in warmer, nearshore waters and polluted estuaries, has reached epidemic proportions.

"Imagine trying to navigate, feed, or even breathe with large, grape-like tumors obstructing your vision or mouth," explains Dr. Lena Karlsson, a leading veterinary pathologist specializing in marine wildlife diseases, speaking from her lab in Florida. "These growths can become so extensive that they impede swimming, make foraging impossible, and even lead to organ failure. It’s a slow, agonizing death for many individuals."

The exact triggers for FP outbreaks are still under intense investigation, but mounting evidence suggests a strong link between the herpesvirus and environmental stressors. Polluted waters, particularly those high in agricultural runoff, industrial chemicals, and persistent organic pollutants, are believed to act as immunosuppressants, making turtles more susceptible to the virus and promoting tumor growth. This devastating synergy turns once-thriving feeding grounds into death traps for vulnerable juveniles and adults.

Ranavirus: The Freshwater and Terrestrial Killer

Moving inland, a different, equally formidable threat lurks in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Ranavirus. This genus of viruses, part of the Iridoviridae family, is a notorious killer, affecting a broad range of ectothermic vertebrates, including amphibians, fish, and reptiles. In turtles, Ranavirus infections can lead to severe systemic disease, characterized by internal hemorrhaging, organ necrosis, and rapid mortality.

"Ranavirus outbreaks are particularly terrifying because of their rapid onset and high mortality rates," states Dr. Mark Jensen, a wildlife veterinarian specializing in chelonian health at a research center in the Midwest. "We’ve seen populations of common snapping turtles, painted turtles, and box turtles decimated in a matter of weeks. The virus spreads quickly, especially in crowded conditions or when water quality is compromised."

The insidious nature of Ranavirus lies in its ability to persist in the environment and infect multiple host species, creating a complex epidemiological web. Climate change plays a role here too; warmer temperatures can stress cold-blooded animals, making them more vulnerable, and can also influence the virus’s replication and transmission rates. Human activities, such as the translocation of turtles for pet trade or rehabilitation without proper quarantine, can inadvertently introduce the virus to new, naive populations, sparking new outbreaks.

Bacterial and Fungal Foes: Shell Rot, URTD, and Beyond

Beyond the high-profile viral threats, a host of bacterial and fungal pathogens persistently plague turtle populations. Bacterial infections, often secondary to injury or weakened immune systems, manifest in various forms:

- Shell Rot: A common ailment, particularly in aquatic turtles, where bacteria or fungi infect the shell, leading to lesions, pitting, and even penetration of the bone. While minor cases might heal, severe shell rot can expose internal organs, lead to systemic infection, and be fatal. Poor water quality and overcrowding are significant contributing factors.

- Respiratory Infections: Bacterial pneumonia is a frequent cause of mortality in both aquatic and terrestrial turtles. Symptoms include lethargy, nasal discharge, open-mouth breathing, and audible wheezing.

- Mycoplasmosis: In terrestrial species like the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) in the southeastern U.S. and the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) in the Southwest, Mycoplasma bacteria are responsible for Upper Respiratory Tract Disease (URTD). This chronic, debilitating illness causes nasal discharge, swollen eyelids, and lethargy, often leading to secondary infections and reduced foraging ability, which can be fatal in arid environments where food and water are scarce. URTD has contributed significantly to the decline of these iconic species.

Fungal infections are also on the rise. A notable example is Emydomyces testavorans, a novel fungus identified in freshwater turtles that causes severe shell lesions and systemic disease. Like many emerging pathogens, its full ecological impact and triggers are still being understood, but it highlights the constant threat of new diseases appearing in vulnerable populations.

The Nexus of Environmental Stressors and Disease

It is crucial to understand that these diseases rarely act in isolation. The alarming rise in their prevalence and severity across Turtle Island is inextricably linked to the profound environmental changes wrought by human activity.

- Pollution: Chemical pollutants, heavy metals, pesticides, and nutrient runoff from agriculture and urban areas act as immunosuppressants, weakening turtles’ defenses against pathogens. They can also directly alter habitats, making them less suitable and increasing stress levels.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events directly impact turtle physiology and behavior. Warmer nests can skew sex ratios, threatening future generations. Droughts concentrate turtles, facilitating disease transmission. Heat stress compromises immune systems.

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: As wetlands are drained, forests are cleared, and coastlines are developed, turtles are pushed into smaller, more degraded areas. This increases population density, which is a perfect recipe for disease transmission, and reduces genetic diversity, making populations less resilient to disease outbreaks.

- Human-Wildlife Interface: Increased contact between humans and turtles (e.g., through recreational activities, pet trade, or rehabilitation efforts without strict biosecurity) can facilitate pathogen exchange. Runoff from human waste can introduce new bacterial and viral strains.

The Call to Action: Research, Conservation, and Respect

Addressing the invisible plague requires a multi-faceted approach rooted in scientific research, robust conservation strategies, and a renewed respect for the natural world. Scientists are employing cutting-edge techniques, from genetic sequencing to satellite telemetry, to track disease spread, identify new pathogens, and understand the complex interplay between hosts, pathogens, and the environment. Veterinary pathologists are working tirelessly to diagnose diseases, develop treatments, and understand immune responses.

Conservation efforts must focus on protecting and restoring critical turtle habitats, mitigating pollution, and combating climate change. Stricter biosecurity protocols are needed in rehabilitation centers and during translocation efforts to prevent the inadvertent spread of pathogens. Furthermore, public awareness campaigns are vital to educate communities about the risks of releasing pet turtles into the wild and the importance of reporting sick or dead animals to wildlife authorities.

The turtles of Turtle Island are more than just reptiles; they are living testaments to resilience, ancient wisdom, and the foundational health of our shared home. Their struggles against an invisible tide of disease serve as a stark warning: the health of these venerable creatures, so intimately tied to the health of their environment, is a direct reflection of our own. To ignore their plight is to ignore the looming threats to the very ecosystems that sustain us all. The time to act, with urgency and reverence, is now, to ensure that the turtle continues to carry the world for generations to come.