Echoes of Resilience: The Creek Nation’s Enduring Saga of Conflict and Survival

The story of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation is not merely a chapter in American history; it is a sprawling epic of power, diplomacy, betrayal, and unyielding resilience. From the fertile river valleys of the American Southeast, where their confederacy flourished for centuries, the Creek people navigated a treacherous landscape of shifting alliances, existential threats, and internecine strife. Their history is a vivid tapestry woven with threads of conflict – with neighboring tribes, with encroaching European empires, and ultimately, with the burgeoning United States – each struggle leaving an indelible mark on their collective spirit and shaping their enduring legacy.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Muscogee people had already established a sophisticated and powerful confederacy, a dynamic union of various tribes, towns, and language groups that stretched across what is now Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and parts of South Carolina. This confederacy, often referred to as the Creek Nation, was a testament to their political acumen and strategic foresight, designed to maintain peace, foster trade, and project strength against external threats from groups like the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw. Internal governance was complex, characterized by a dual system of "Red" (war) towns and "White" (peace) towns, which managed different aspects of civic and ritual life, often alternating between leadership roles. This intricate political structure, while generally robust, also harbored the potential for deep divisions, particularly when external pressures mounted.

The arrival of European powers – first the Spanish in the 16th century, followed by the French and British in the 17th and 18th centuries – dramatically altered the geopolitical landscape for the Creek. The Muscogee quickly learned to play these imperial rivals against one another, masterfully leveraging their strategic location and military prowess to secure favorable trade agreements and protect their vast territorial claims. They became crucial partners in the deerskin trade, integrating European goods like guns, tools, and textiles into their economy and daily lives.

This era was marked by a series of complex and often brutal proxy wars. During the Yamasee War (1715-1717), the Creek initially sided with the Yamasee and other tribes against the British in South Carolina, a conflict that nearly destroyed the colony. Though the uprising was ultimately suppressed, the Creek’s involvement demonstrated their formidable power and their willingness to assert their sovereignty through force. They honed their diplomatic skills, often maintaining a delicate neutrality while secretly aligning with whichever power offered the best terms or posed the least immediate threat. As the historian Michael D. Green notes, "The Creeks were masters of the balance of power, playing the Spanish, French, and English against each other to their own advantage for nearly a century."

The American Revolution introduced a new, formidable player: the nascent United States. The Creek Nation found itself caught between a weakening British Empire, which many Creeks had long allied with, and the revolutionary American colonies, whose land hunger was already evident. Divisions emerged, though many Creeks, particularly those led by the brilliant and charismatic Alexander McGillivray, sided with the British, seeing them as the lesser of two evils compared to the land-hungry Americans. McGillivray, a mixed-blood leader with Scottish and Muscogee heritage, became a pivotal figure. He skillfully united many Creek factions, negotiated with Spanish, British, and American officials, and for a time, successfully defended Creek sovereignty against American encroachment. His efforts culminated in the Treaty of New York (1790) with the United States, which, though contentious, recognized Creek land boundaries and established a relationship, albeit a fraught one, with the new nation. However, the ink was barely dry before American settlers began violating its terms, foreshadowing future conflicts.

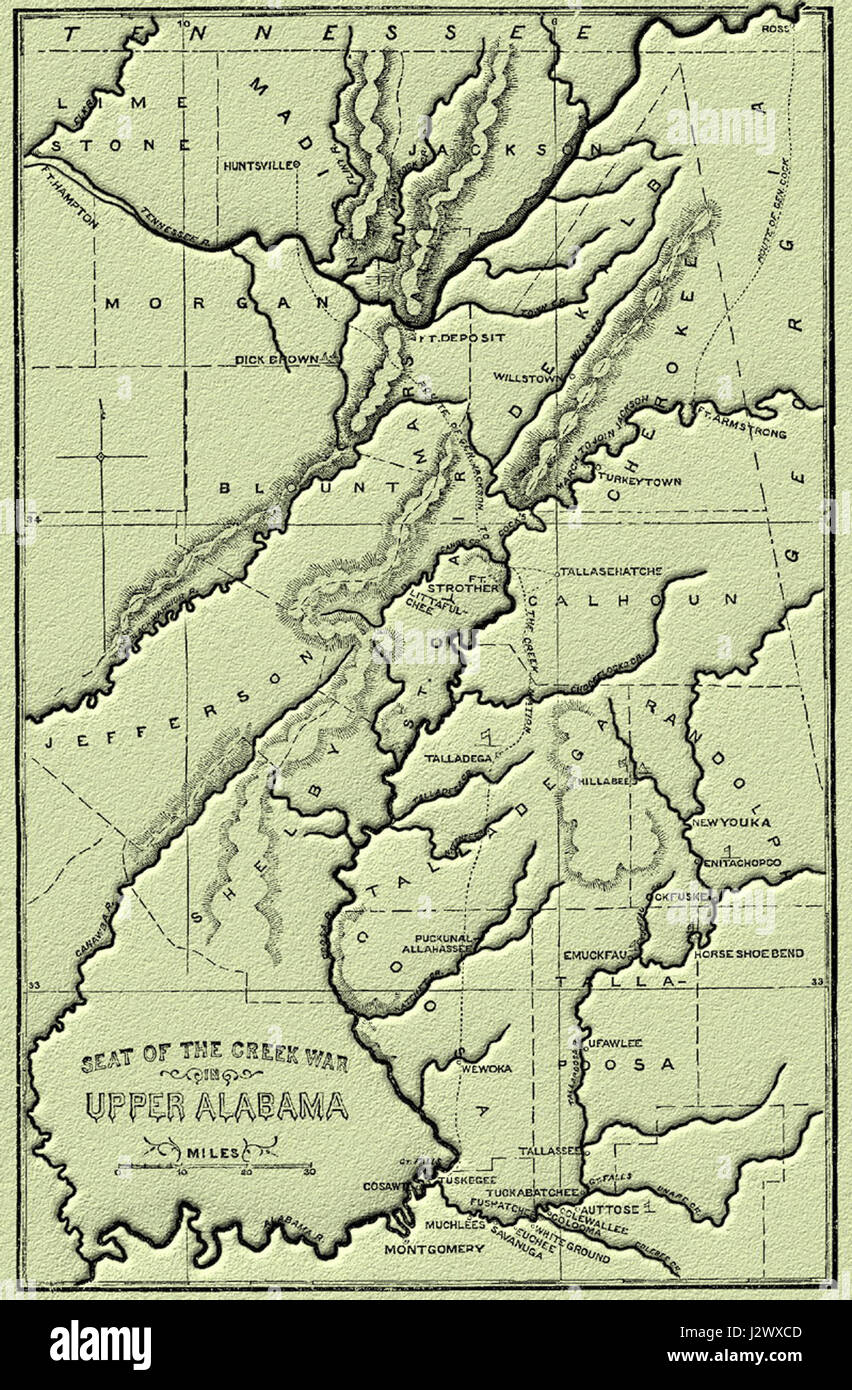

The early 19th century brought the most devastating period of conflict for the Creek Nation: the Creek War of 1813-1814, a brutal civil war that spiraled into a larger conflict with the United States. This war was the culmination of escalating internal tensions, exacerbated by external pressures. On one side were the "Red Sticks," a faction primarily from the Upper Creek towns, who advocated a return to traditional ways, resisted American cultural assimilation, and were influenced by the pan-Indian nativist movement of Tecumseh. They sought to purify Creek society and violently resist American expansion. On the other side were the "White Sticks," predominantly from the Lower Creek towns, who were generally more accommodationist, often of mixed heritage, and engaged in agriculture and trade with American settlers. They believed that adopting some American practices and maintaining peace was the best path to survival.

The conflict erupted in full force after the Battle of Burnt Corn in July 1813, where Red Sticks ambushed a detachment of American militia and pro-American Creeks. This was followed by the infamous Fort Mims Massacre in August 1813, where Red Sticks overran a stockade, killing hundreds of settlers and mixed-blood Creeks. This horrific event galvanized American public opinion and provided the justification for a full-scale military intervention led by General Andrew Jackson, whose forces included U.S. regulars, state militias, and Cherokee and Lower Creek allies.

The Creek War was a brutal affair, fought with immense ferocity on both sides. Jackson systematically campaigned against the Red Sticks, culminating in the decisive Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814. Here, Jackson’s forces, numbering around 3,300 men (including some 600 Cherokee and 500 Lower Creek warriors), attacked a fortified Red Stick stronghold on a bend of the Tallapoosa River. The Red Sticks, led by Menawa, fought valiantly, but were ultimately overwhelmed. An estimated 800 Red Stick warriors were killed, effectively breaking their military power.

The aftermath was catastrophic. Despite the crucial role played by Lower Creek warriors in defeating the Red Sticks, Andrew Jackson, leveraging his victory, imposed the Treaty of Fort Jackson in August 1814. This treaty forced the entire Creek Nation, including those who had fought alongside Jackson, to cede 23 million acres of land – more than half of their remaining territory – to the United States. Jackson infamously declared, "The Creek Nation has been too long under the influence of the British and Spanish, and the time has come for them to feel the strong hand of the United States." This act of collective punishment, dispossessing even their allies, underscored the ruthless nature of American expansionism and set a chilling precedent for future dealings with Native American nations.

Despite this devastating loss, the Creek Nation attempted to rebuild and adapt. They established a written constitution, developed a legal system, and embraced some agricultural practices and institutions of the U.S. in a desperate effort to retain their remaining lands and sovereignty. However, the insatiable demand for cotton land and the political power of figures like Andrew Jackson, now president, ensured their efforts would be futile.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by Jackson, sealed their fate. Despite protests and legal challenges, the U.S. government pushed for the removal of all southeastern tribes to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The Treaty of Washington (1832), signed by a minority faction of Creek leaders without the consent of the majority, ceded the last of their lands east of the Mississippi. This fraudulent treaty led to widespread unrest and what is sometimes referred to as the "Creek War of 1836," a final, desperate resistance against removal. This uprising was brutally suppressed, leading to the forced removal of thousands of Creeks, often in chains, at gunpoint, and under horrifying conditions.

The journey west, part of the infamous Trail of Tears, was a harrowing ordeal. Thousands perished from disease, starvation, and exposure. "We are an unhappy people," lamented Opothleyahola, a prominent Creek leader, as his people were driven from their ancestral lands. The forced removal shattered families and communities, severing their deep connection to generations of homeland.

Yet, the Creek Nation endured. In Indian Territory, they began the arduous process of rebuilding. They re-established their government, revitalized their cultural practices, and adapted to a new environment. The conflicts they faced – from internal divisions to imperial struggles to the genocidal policies of the United States – forged a resilient people. Today, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation thrives as a sovereign nation in Oklahoma, a testament to their unwavering spirit, cultural strength, and the enduring power of a people who, despite monumental losses and continuous struggles, refused to be extinguished. Their history is a powerful reminder that while conflicts can devastate, they can also forge an unyielding resolve to survive, adapt, and ultimately, reclaim their narrative and their future.