Beyond Orion and Ursa Major: Unveiling the Cosmos of Turtle Island’s Indigenous Astronomies

For centuries, the Western world has largely viewed the night sky through the lens of Greco-Roman mythology, populating the celestial sphere with gods, heroes, and beasts whose stories were etched into the constellations we recognize today. Ursa Major, Orion, Cassiopeia – these patterns, and the narratives they carry, have become the dominant global standard. Yet, across Turtle Island—a name many Indigenous peoples use for North America—the stars tell vastly different stories, reflect unique worldviews, and hold profound practical, spiritual, and cultural significance that predates European contact by millennia. Indigenous astronomy on Turtle Island is not merely an alternative mapping of the sky; it is a holistic science, deeply interwoven with land, language, ceremony, and survival.

To understand Indigenous astronomy is to step beyond the arbitrary lines connecting stars into familiar shapes and instead perceive the cosmos as a living, breathing entity, intrinsically linked to life on Earth. Unlike Western astronomy, which often seeks to dissect and categorize, Indigenous star knowledge is relational, emphasizing interconnectedness. It is a science born from generations of meticulous observation, passed down through oral traditions, stories, songs, and ceremonies, rather than written texts. This knowledge guided everything from seasonal migrations and agricultural cycles to navigation, social structures, and spiritual well-being.

The stars were not just distant lights; they were celestial calendars, precise agricultural guides, and profound moral compasses. The appearance of certain star clusters signaled the time for planting specific crops, harvesting medicines, or hunting particular animals. For example, the setting of the Pleiades (known by various names like the "Seven Sisters" or "Little Ones" across many traditions) often marked the optimal time for planting corn, beans, and squash in many Woodland and Plains communities. The position of the Big Dipper (another widely recognized asterism) could indicate the direction of a hunting party or the passage of seasons.

Beyond utility, Indigenous astronomy is deeply spiritual, often serving as the foundational framework for creation stories and ethical teachings. The sky world is frequently depicted as the original home of humanity or the dwelling place of powerful spirits and ancestors. These narratives imbue the celestial bodies with character and purpose, making the cosmos a dynamic participant in the human experience. They teach lessons about reciprocity, respect for the natural world, and the cyclical nature of life and death.

Consider the Anishinaabe people, whose traditional territories span the Great Lakes region. For them, the asterism commonly known as the Big Dipper is often seen as Ojiig, the Fisher. The story tells of how Ojiig, a nimble and cunning animal, created winter by shaking the Star Blanket, and how the Creator eventually placed him in the sky as a reminder of his power and as a marker of the seasons. Other Anishinaabe traditions see the Big Dipper as Miskwaadesi, the Turtle, a sacred creature central to their creation stories, carrying the weight of Turtle Island on its back. The movement of these sky figures across the night sky marked the passage of time and influenced activities on the land. Wilfred Buck, an Anishinaabe elder and star knowledge keeper, emphasizes the sophistication of these systems: "Our people knew all the constellations, and they weren’t just for pretty pictures. They were for survival, for guidance, for ceremonies, for everything."

The Lakota people, from the Great Plains, have an equally rich astronomical tradition. The Big Dipper, for them, is Naŋkaŋ Maŋku, a bear being pursued by three hunters (the three stars of the "handle"). This narrative reflects the vital hunting traditions of the Lakota and their deep connection to the buffalo. The Pleiades, known as Wičháŋȟpi Huŋkékuyapi (literally "star grandmothers" or "star mothers"), are revered as ancestors and hold special significance in ceremonies, particularly those related to healing and connection to the spiritual realm. These constellations are not static images but dynamic storyboards that impart wisdom and guide cultural practices.

For the Diné (Navajo) people of the Southwest, the cosmos is meticulously mapped, reflecting their philosophy of Hózhó, or balance and beauty. Their constellations are categorized into "male" and "female," "traveling" and "fixed." Dilyéhé, the Pleiades, is a central figure, representing the planting season and the importance of agriculture. It is associated with the beginning of the Diné calendar and serves as a teaching tool for children, symbolizing order and the importance of family. Nahookos Bika’ii (Revolving Male, corresponding to Ursa Major/Big Dipper) and Nahookos Bi’áád (Revolving Female, corresponding to Ursa Minor/Little Dipper) encircle the North Star, representing the eternal motion and stability of the universe, and are crucial for navigation and maintaining order. These constellations are not just observed; they are sung about, prayed to, and lived with.

This intricate knowledge was not confined to dusty texts but woven into the fabric of oral traditions, passed down from elders to youth through storytelling circles, ceremonies, and hands-on learning. The language itself often carries astronomical insights, with specific terms for different stars, planets, and celestial phenomena that convey their cultural meaning and practical applications. The cyclical nature of these teachings mirrored the cycles of the seasons and the stars themselves, ensuring that knowledge was continually reinforced and adapted.

The arrival of European colonizers brought profound disruption to these sophisticated systems. The imposition of Western calendars, religions, and educational models often suppressed Indigenous languages and worldviews, including their astronomical traditions. Children were removed from their families and placed in residential schools, where their cultural knowledge was actively eradicated. This rupture in intergenerational transmission led to the loss of invaluable astronomical wisdom for many communities.

However, despite centuries of attempted assimilation, Indigenous astronomy on Turtle Island has proven remarkably resilient. Today, a powerful movement is underway to reclaim and revitalize these ancient astronomical traditions. Indigenous elders, knowledge keepers, and scientists are working tirelessly to document, teach, and share this wisdom, often blending traditional knowledge with contemporary scientific methods.

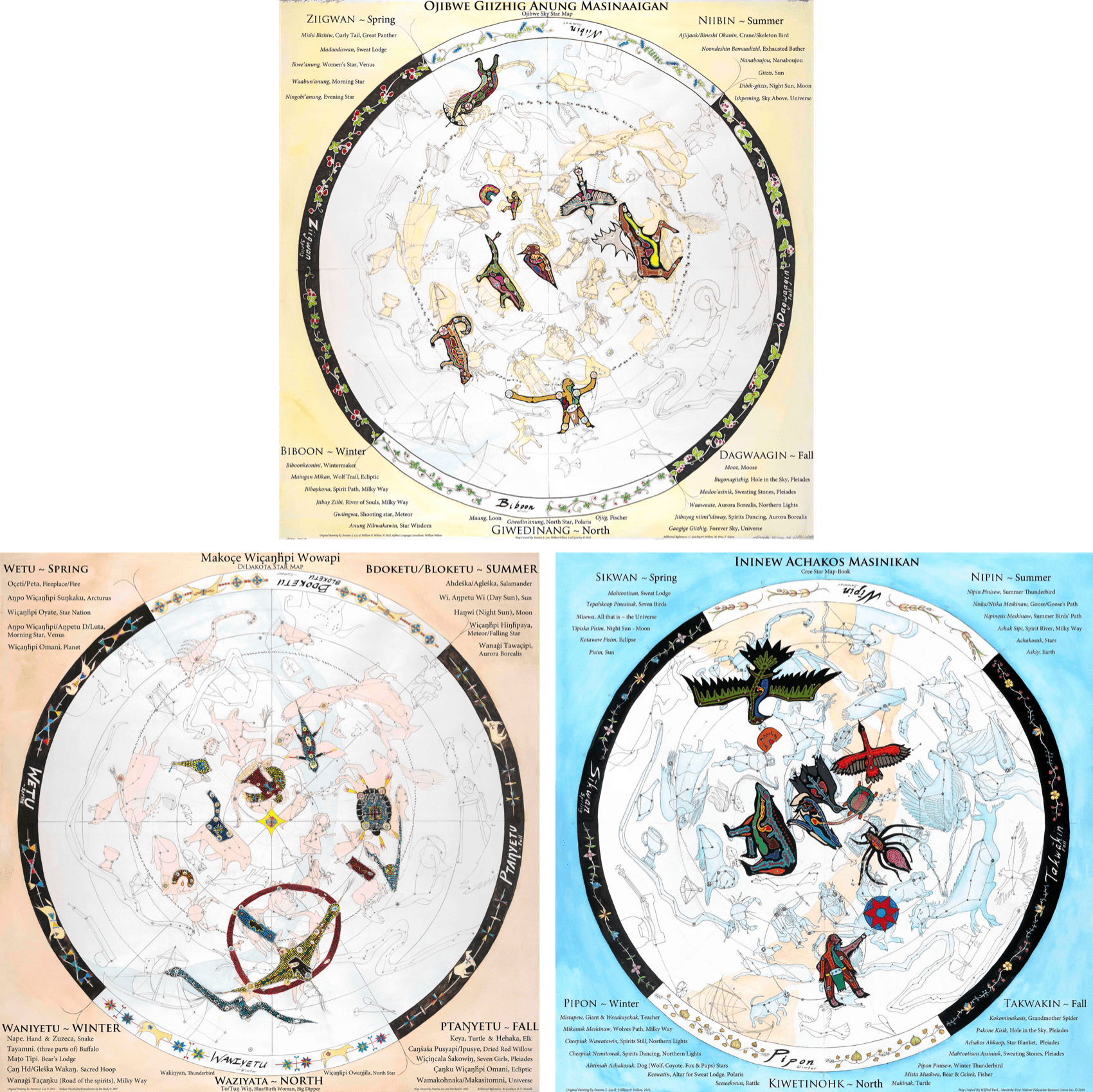

Annette S. Lee (Ojibwe/Lakota), an astrophysicist and founder of the Native Skywatchers project, is a leading figure in this revitalization. Her work bridges Western and Indigenous science, demonstrating that these systems are not mutually exclusive but offer complementary perspectives. "Our elders always told us the stars were like our grandmothers and grandfathers," Lee states. "They were our first teachers. We just need to remember how to listen to them again." Projects like Native Skywatchers create culturally relevant educational materials, star maps, and curricula that bring Indigenous astronomical knowledge back into classrooms and communities.

This resurgence is not just about historical preservation; it is about empowerment and self-determination. Reclaiming star knowledge reconnects Indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands, languages, and identities. It offers a powerful counter-narrative to the colonial legacy, asserting the validity and sophistication of Indigenous scientific thought. It also provides a unique and valuable perspective for all humanity, encouraging a more holistic and respectful relationship with the cosmos and our planet.

The stars above Turtle Island continue to shine, inviting all to look beyond familiar patterns and discover the rich tapestries of Indigenous astronomical knowledge. These constellations, born from millennia of observation and deep cultural connection, offer not just a different way of seeing the sky, but a different way of understanding our place within the universe—one rooted in reciprocity, respect, and the profound wisdom of those who have gazed at the stars from this land since time immemorial. By listening to these ancient stories, we gain not only scientific insight but also a deeper appreciation for the diverse ways humanity has sought to comprehend the vast, silent beauty of the cosmos.