Echoes of Resilience: Connecticut’s Tribal Nations and the Enduring Spirit of Cultural Preservation

In the verdant embrace of Connecticut’s landscape, amidst the quiet hum of modernity, lies a profound testament to the power of endurance and identity: the thriving cultural preservation efforts of its indigenous tribal nations. Far from being relegated to the annals of history, the Mohegan and Mashantucket Pequot tribes, alongside other smaller indigenous communities, actively champion a vibrant living culture, defying centuries of systemic oppression, displacement, and attempts at assimilation. Their story is not just one of survival, but of a fierce, unyielding commitment to their heritage, language, traditions, and the sacred connection to their ancestral lands.

For millennia before European contact, the lands now known as Connecticut were home to a diverse tapestry of Algonquian-speaking peoples. The Mohegan, Pequot, Nipmuc, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, and others lived in complex, self-sufficient societies, guided by deep spiritual beliefs, sophisticated agricultural practices, and intricate social structures. Their territories were defined by rivers, forests, and coastline, their lives interwoven with the natural rhythms of the seasons. Oral histories, ceremonies, and the passing down of skills like basket weaving, wampum creation, and traditional healing formed the bedrock of their cultural continuity.

The arrival of European colonists in the 17th century irrevocably altered this landscape. Disease, land disputes, and escalating conflicts decimated indigenous populations and shattered their way of life. The Pequot War of 1637 stands as a grim marker, a brutal conflict that saw the near annihilation of the Pequot people, their lands seized, and survivors enslaved or dispersed. For the Mohegan, while they allied with the English against the Pequot, their sovereignty was gradually eroded through treaties and land sales often coerced or misunderstood. The subsequent centuries brought further pressures: forced assimilation, the outlawing of traditional practices, the loss of language, and the constant threat of having their very existence denied. Many tribal members were forced to hide their heritage, blending into the wider society to survive, their cultural practices driven underground.

Yet, the spirit of these nations refused to be extinguished. Through generations of quiet resistance, the elders held onto fragments of knowledge, stories, and practices, often in secret, nurturing the embers of their heritage. This period, sometimes referred to as the "hidden years," was crucial for the eventual resurgence. Families continued to gather, share meals, and pass down oral traditions, ensuring that the thread of their identity, however thin, remained unbroken.

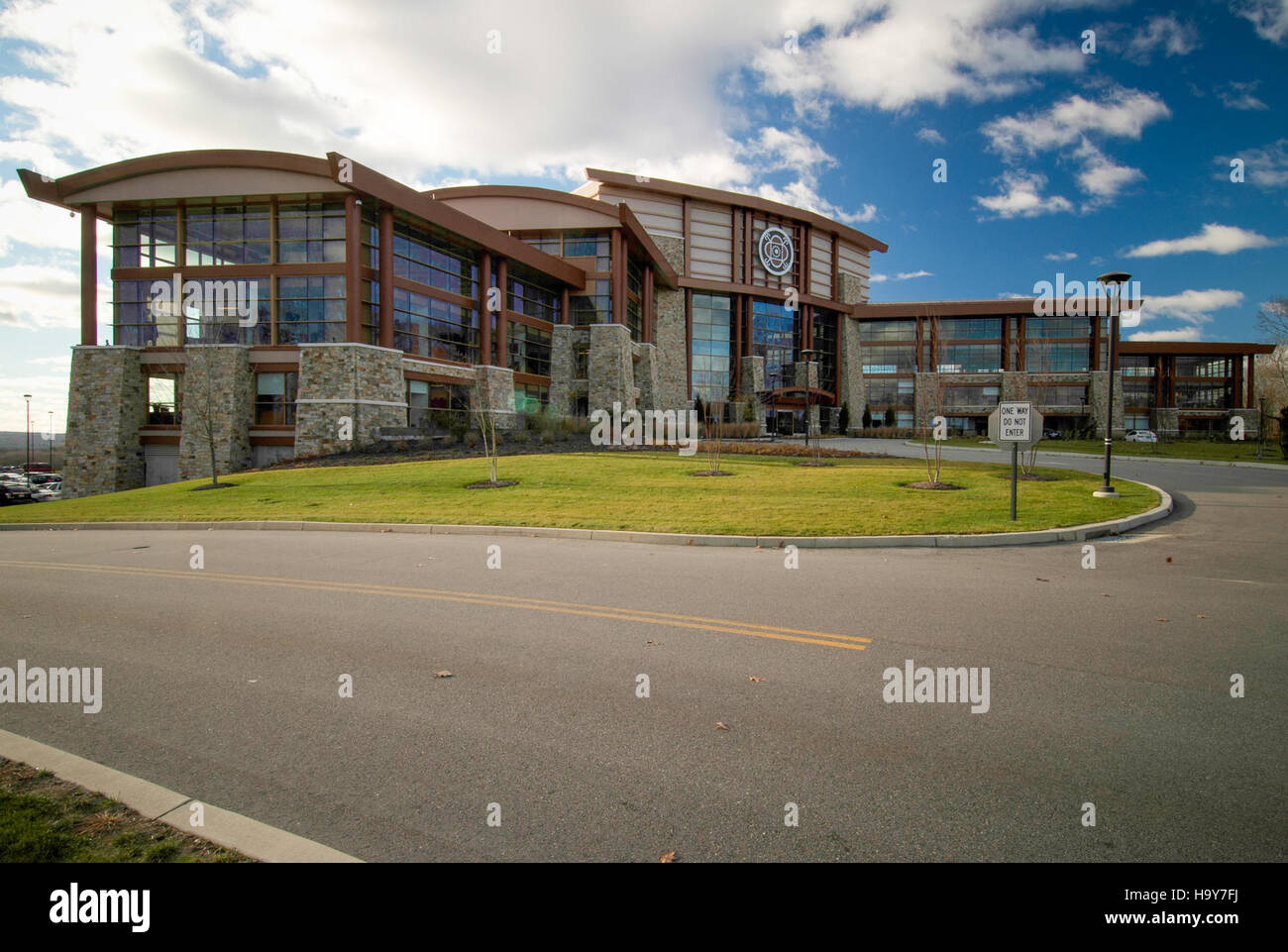

The latter half of the 20th century marked a pivotal turning point, characterized by a renewed push for federal recognition and self-determination. The Mashantucket Pequot, after years of legal battles, achieved federal recognition in 1983. This was a monumental victory, restoring their sovereign status and opening doors to economic development. The Mohegan Tribe followed suit, receiving federal recognition in 1994. This hard-won sovereignty became the catalyst for an unprecedented era of cultural revitalization, primarily fueled by the economic engines of their highly successful casino resorts: Foxwoods Resort Casino for the Mashantucket Pequot and Mohegan Sun for the Mohegan Tribe.

While often viewed through the narrow lens of gaming and entertainment, these enterprises became the improbable yet potent catalysts for cultural preservation. The significant revenue generated provided the financial autonomy necessary to invest heavily in programs, institutions, and initiatives dedicated to reclaiming, documenting, and celebrating their heritage. It allowed these nations to become proactive stewards of their own history, rather than relying on external, often misinformed, interpretations.

The Pillars of Preservation: Language, Museums, and Living Traditions

One of the most profound and challenging aspects of cultural preservation is language revitalization. For the Mashantucket Pequot, the Pequot language – a dialect of Eastern Algonquian – was considered dormant for over a century. However, through painstaking research of historical documents, missionary texts, and the dedicated efforts of linguists and tribal members, the language is experiencing a remarkable rebirth. The Mashantucket Pequot Language Department has developed curricula, dictionaries, and classes, teaching the language to a new generation. Children are now learning Pequot in tribal schools, reconnecting with the worldview embedded within their ancestral tongue. As one tribal elder once remarked, "Our language is the heartbeat of our people. To speak it is to bring our ancestors closer."

The Mohegan Tribe has undertaken similar efforts with their Mohegan language, developing resources and encouraging its use in ceremonies and daily life, ensuring that the distinct nuances of their cultural expression are not lost. These language initiatives are more than just academic exercises; they are profound acts of cultural reclamation, rebuilding a vital bridge to their past and strengthening their collective identity.

Museums and cultural centers stand as physical manifestations of this commitment. The Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center, a magnificent 308,000-square-foot facility opened in 1998, is an internationally recognized institution. It offers an immersive experience, from a reconstructed 16th-century Pequot village to interactive exhibits chronicling tribal history from pre-colonial times to the present day. Its extensive archives and research library serve as invaluable resources for scholars and tribal members alike, ensuring that historical narratives are told from an indigenous perspective. The museum’s existence is a powerful declaration: "We are still here, and our story is complex, resilient, and enduring."

Similarly, the Mohegan Tribe proudly maintains the Tantaquidgeon Museum, the oldest Native American-operated museum in the United States, established in 1931 by the renowned Mohegan medicine woman and anthropologist, Gladys Tantaquidgeon, along with her father, John, and brother, Harold. This smaller, intimate museum houses a rich collection of Mohegan artifacts, traditional crafts, and historical documents, serving as a direct link to the tribe’s continuous presence and cultural practices. Gladys Tantaquidgeon, who lived to be 106, embodied the spirit of preservation, famously urging her people to "Always remember who you are and where you come from." Her legacy continues to inspire generations.

Beyond formal institutions, cultural preservation manifests in living traditions. Traditional arts and crafts, once suppressed, are now openly celebrated and taught. Basket weaving, a skill passed down through generations, continues to thrive, with master weavers teaching apprentices the intricate techniques and cultural significance of each pattern. Wampum, the shell beads historically used for currency, ceremonial purposes, and recording history, is being revitalized, its creation an act of reconnecting with ancestral craftsmanship and diplomacy. Storytelling, powwows, Green Corn ceremonies, naming ceremonies, and other traditional gatherings are regular occurrences, fostering a sense of community, spiritual connection, and intergenerational knowledge transfer. These events are not merely performances; they are vital expressions of a living culture, adapted and sustained in the modern era.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite these remarkable successes, the path of cultural preservation is not without its challenges. The lure of mainstream culture, the ongoing fight against stereotypes, and the need to engage younger generations in traditional practices are constant considerations. There’s a delicate balance between honoring tradition and adapting to contemporary life. The tribes actively address these issues through educational programs, youth mentorship, and by demonstrating the relevance of their heritage in a modern context. Environmental stewardship, deeply rooted in indigenous philosophies, also plays a crucial role, as tribes work to protect and restore ancestral lands and waters, recognizing that the health of the land is intrinsically linked to the health of their culture.

The story of Connecticut’s tribal nations, particularly the Mohegan and Mashantucket Pequot, is a powerful narrative of resilience, self-determination, and profound cultural strength. It is a testament to the fact that even after centuries of hardship, a people can reclaim their voice, rebuild their institutions, and ensure their heritage endures. Their efforts serve as a beacon of hope and a model for other indigenous communities worldwide, demonstrating that cultural preservation is not about clinging to a static past, but about nurturing a vibrant, evolving identity that honors its roots while confidently stepping into the future. They remind us that the true wealth of a nation lies not just in its economic power, but in the richness and continuity of its cultural soul.