The Saltwater Path: Unraveling America’s First Journeys by the Pacific

For decades, the story of how humans first arrived in the Americas was etched in ice and land: a single, dramatic crossing of the Bering land bridge, followed by a trek through an ice-free corridor in the heart of the continent. This narrative, often associated with the distinctive Clovis culture, dominated archaeological thought for much of the 20th century. It painted a picture of hardy, inland hunters venturing into a vast, untamed wilderness.

Today, however, a compelling and increasingly well-supported alternative is challenging this long-held dogma. The Coastal Migration Theory, often dubbed the "Kelp Highway" hypothesis, suggests a radically different, and perhaps far earlier, route into the Americas: a journey along the Pacific coast, navigated by skilled mariners who saw the ocean not as a barrier, but as a highway teeming with life. This burgeoning theory reshapes our understanding of the ingenuity of early humans and the very timeline of their arrival in the New World.

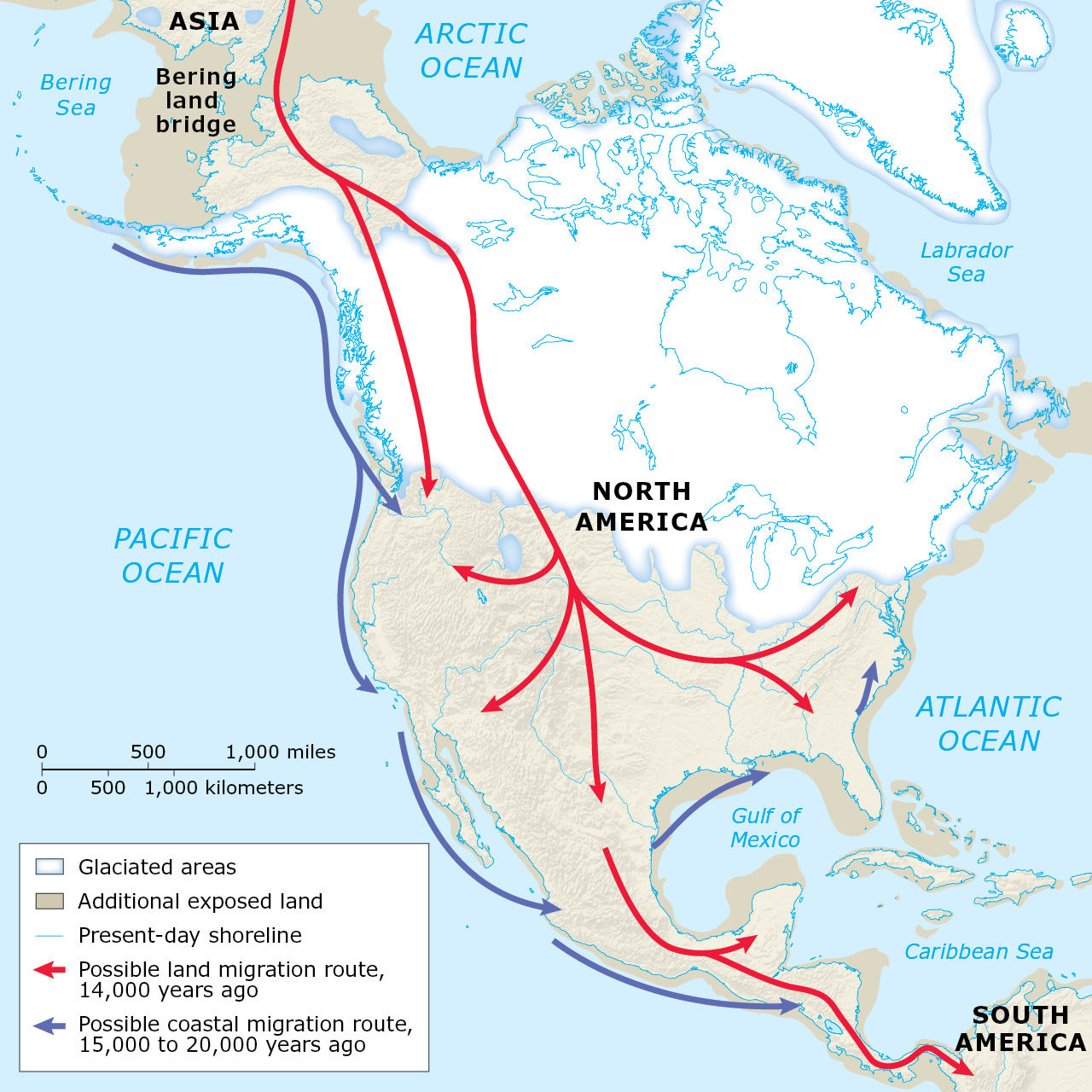

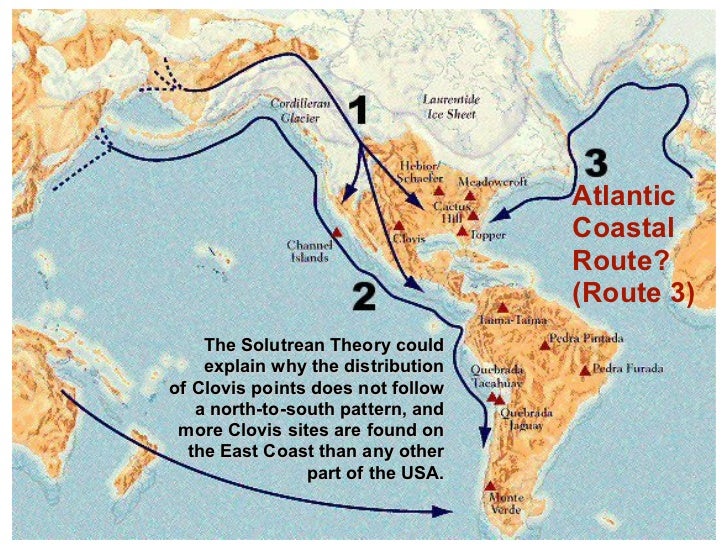

The traditional "Clovis First" model posited that the ancestors of Native Americans crossed Beringia, a vast land bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska, during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) when sea levels were significantly lower. Once in Alaska, they waited for an "ice-free corridor" to open between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets, allowing them to push south into the North American interior. The distinctive fluted projectile points of the Clovis culture, dated to around 13,000 years ago, were considered the earliest unequivocal evidence of human presence, leading to the belief that all subsequent cultures descended from these pioneers. This theory held sway due to its apparent simplicity and the widespread distribution of Clovis artifacts across the continent.

However, the edifice of Clovis First began to show cracks as early as the 1970s. Archaeological sites began to emerge with dates that stubbornly predated Clovis. Monte Verde in Chile, meticulously excavated by Tom Dillehay, revealed a remarkably preserved settlement dating back at least 14,500 years, and possibly even earlier. Its diverse toolkit and diet, including evidence of coastal resources, shattered the notion that Clovis was the sole ancestor. Other sites like Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania, Paisley Caves in Oregon, and Gault in Texas offered additional, albeit sometimes debated, pre-Clovis dates. The very existence of these sites, some located thousands of miles south of the proposed ice-free corridor, posed a significant problem: the corridor itself wasn’t reliably open until around 13,000 years ago – too late for these early arrivals.

This chronological conundrum opened the door for the Coastal Migration Theory. Proponents of this theory argue that long before the interior ice corridor became passable, the Pacific coast of Beringia and North America may have offered a more hospitable and accessible route. During the LGM, sea levels were approximately 100-120 meters lower than today, exposing vast stretches of continental shelf. While the interior was locked under colossal ice sheets, a narrow, ice-free coastal strip, dotted with refugia and fed by glacial meltwater, could have existed along the coast of Alaska and British Columbia.

The core of the Coastal Migration Theory rests on the concept of the "Kelp Highway." This idea, championed by archaeologists like Jon Erlandson, proposes that early coastal migrants would have followed a remarkably productive marine ecosystem stretching from Japan to Baja California. Kelp forests, found in nutrient-rich cold waters, provide a dense, three-dimensional habitat that supports an astonishing array of marine life: fish, shellfish, sea otters, seals, and sea birds. For maritime-adapted hunter-gatherers, this environment would have been an incredibly rich and reliable food source, providing everything needed for survival and migration. "Imagine," Erlandson suggests, "a superhighway of food and resources, a linear oasis that would have made coastal travel much easier than battling through an icy, barren interior."

The logic is compelling. Traveling by water, in relatively stable boats, would have been far more efficient and less arduous than trekking across vast, unknown, and possibly frozen terrestrial landscapes. These early mariners would have possessed sophisticated knowledge of tides, currents, and marine resources. Their boats, perhaps simple skin-covered kayaks or canoes, would have allowed them to leapfrog down the coast, utilizing islands as stepping stones and safe havens.

Evidence for the Coastal Migration Theory, though often tantalizingly submerged beneath today’s higher sea levels, is accumulating. One of the most significant pieces comes from the Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California. Here, archaeological sites have yielded evidence of sophisticated maritime toolkits and diets heavily reliant on marine resources, dating back as far as 12,000-13,000 years ago. The discovery of Arlington Springs Woman on Santa Rosa Island, dating to approximately 13,000 years ago, represents some of the oldest human remains in North America, found on an island that would have been isolated from the mainland even with lower sea levels. This suggests a capacity for seafaring well over a millennium before the ice-free corridor was open.

Further north, on Haida Gwaii (the Queen Charlotte Islands) in British Columbia, submerged archaeological landscapes are slowly yielding clues. While direct human artifacts are scarce, geological and environmental studies suggest that these islands, which were partially ice-free during the LGM, could have served as crucial refugia and waypoints for coastal travelers. The very presence of people at Monte Verde, thousands of miles south and relatively quickly after the proposed opening of the coastal route, points to a rapid dispersal that is more consistent with coastal travel than a slow overland migration.

Genetic studies also lend weight to the Coastal Migration Theory. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome markers in Indigenous populations across the Americas reveals patterns that suggest a rapid initial dispersal along the Pacific Rim, with subsequent inland movements. The genetic diversity found in some coastal groups further supports the idea of ancient, enduring coastal populations.

Of course, the Coastal Migration Theory is not without its challenges. The primary difficulty lies in the fact that much of the direct evidence lies underwater. The rising sea levels since the LGM have submerged ancient coastlines, settlements, and potential boat landing sites, making archaeological investigation incredibly difficult and expensive. "It’s like trying to find a needle in a haystack, when the haystack is at the bottom of the ocean," notes one archaeologist. Despite these obstacles, advances in underwater archaeology, remote sensing, and paleoenvironmental reconstruction are steadily revealing more about these lost worlds.

It’s also important to note that the Coastal Migration Theory doesn’t necessarily invalidate the Beringia land bridge crossing. Rather, it offers a more complex and nuanced picture of early American settlement. It’s entirely plausible that multiple waves of migration occurred, using different routes at different times, with coastal groups eventually venturing inland, and overland migrants also contributing to the genetic and cultural tapestry of the continent. The initial coastal pioneers may have established a foundational population, followed by later movements through the interior corridor once it became viable.

The shift from a singular, ice-age trek to a multi-faceted exploration, encompassing both land and sea, speaks volumes about the adaptability and resourcefulness of early humans. The story of the first Americans is no longer a simple linear narrative but a dynamic, unfolding mystery. The Saltwater Path, the Kelp Highway, reminds us that the ocean, often seen as an intimidating expanse, was for our distant ancestors a vibrant, life-sustaining thoroughfare, guiding them to new worlds and shaping the very foundations of the Americas. As research continues, the whispers from beneath the waves promise to reveal even more about these intrepid mariners and their epic journey across the Pacific Rim, forever changing our understanding of human history.