The Enduring Echoes of the Tomol: A Journey Through Chumash History

Along the sun-drenched coast of Central California, where the Santa Ynez Mountains meet the Pacific Ocean, lies a land steeped in millennia of human history. Here, for at least 13,000 years, the Chumash people have woven their lives into the fabric of the landscape, their stories carried on the ocean breeze and etched into the very rock formations. From the sophisticated artistry of their plank canoes to their profound spiritual connection to the land and sea, the Chumash represent one of North America’s most remarkable and resilient indigenous cultures, a legacy that continues to resonate powerfully today.

A Deep History: Masters of the Maritime World

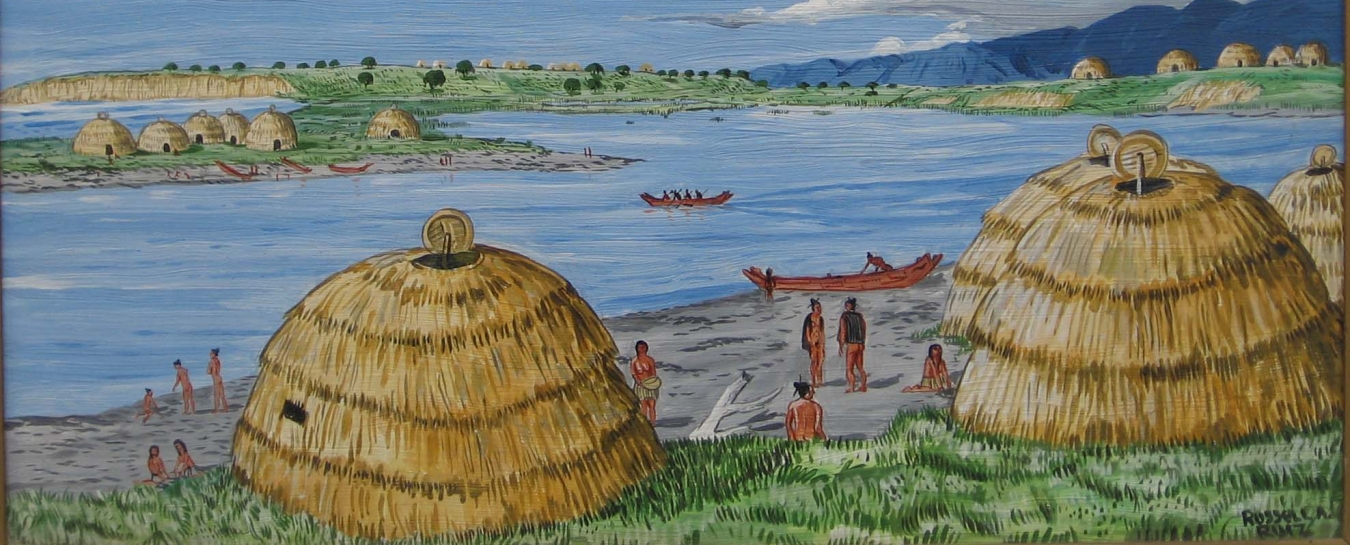

The Chumash homeland stretched from Malibu Canyon to San Luis Obispo, encompassing the fertile valleys, coastal plains, and the four northern Channel Islands: Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, San Miguel, and Anacapa. This diverse environment fostered a unique and highly adapted society. Unlike many inland tribes, the Chumash were consummate mariners, their lives inextricably linked to the ocean.

Their defining innovation, and perhaps the most iconic symbol of their ingenuity, was the tomol – a sophisticated, ocean-going plank canoe. Crafted from redwood drift logs, meticulously cut, shaped, and sewn together with plant fibers, then sealed with natural asphaltum (tar) found in coastal seeps, the tomol was a marvel of pre-industrial engineering. These swift, maneuverable vessels, often up to 30 feet long, allowed the Chumash to navigate the treacherous Channel Islands, trade extensively, and harvest the rich bounty of the Pacific.

"The tomol wasn’t just a boat; it was the heart of Chumash culture," notes Dr. John R. Johnson, curator of anthropology at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. "It facilitated trade, warfare, social interaction, and access to resources that were simply unavailable to inland groups. Its construction required incredible skill, cooperation, and a deep understanding of the sea."

With the tomol, Chumash fishermen pursued deep-sea species like halibut, tuna, and swordfish, while hunters targeted seals, sea lions, and even whales. Shellfish, mussels, and abalone were harvested from the intertidal zones, and the land provided acorns, seeds, berries, and game. This abundant and varied diet supported a large and complex society, with estimates placing their pre-contact population between 10,000 and 20,000 individuals.

Chumash society was highly organized, featuring distinct social classes, specialized craftspeople, and a sophisticated political structure of independent villages often led by hereditary chiefs (wot). They were renowned for their intricate basketry, fine stone tools, and exquisite shell bead money, which served as a regional currency. Their spiritual life was rich and deeply connected to the natural world, expressed through elaborate ceremonies, a cosmology that envisioned three worlds (upper, middle, lower), and the enigmatic rock art found in painted caves, depicting celestial beings, animals, and abstract symbols, some believed to be astronomical observations or shamanic visions.

The Spanish Crucible: Collision and Catastrophe

The tranquil existence of the Chumash was shattered with the arrival of European explorers. In 1542, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo became the first European to make contact, sailing into Chumash waters. His descriptions speak of a numerous and welcoming people, living in well-established villages. However, it was the arrival of the Spanish mission system more than two centuries later that would prove catastrophic.

Beginning in 1772 with Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, and continuing with Mission San Buenaventura (1782), Mission Santa Barbara (1786), and Mission La Purisima Concepcion (1787), the Spanish established a chain of religious outposts directly in the heart of Chumash territory. The stated goal was to "civilize" and Christianize the native populations, but the reality was often brutal.

Chumash people were coerced or forced into the missions, where their traditional way of life was systematically dismantled. They were compelled to adopt Christianity, speak Spanish, perform forced labor, and abandon their ceremonies, language, and cultural practices. The communal life of the missions, coupled with new diseases to which the Chumash had no immunity (smallpox, measles, influenza), led to a devastating demographic collapse. Within a few generations, the Chumash population plummeted by an estimated 90 percent.

"The mission era was a profound disruption, a cultural and demographic catastrophe for the Chumash," states a historian specializing in California indigenous history. "Their sophisticated social structures were broken, their spiritual beliefs suppressed, and their very existence threatened. Yet, even under these immense pressures, pockets of Chumash culture and resistance endured."

One notable instance of resistance was the Chumash Revolt of 1824, where Chumash neophytes at Mission Santa Inés, La Purísima, and Santa Barbara rose up against the harsh conditions and abuses of the mission system. Though ultimately suppressed, it demonstrated the Chumash people’s unwavering spirit and desire for freedom.

Survival, Resilience, and Revitalization

Following Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821 and the subsequent secularization of the missions in the 1830s, the Chumash faced a new set of challenges. Their ancestral lands were divided into vast rancho grants, often leaving them landless and marginalized. The California Gold Rush in 1849 brought a flood of American settlers, further dispossessing indigenous communities and intensifying racial prejudice.

Despite these relentless pressures, the Chumash persisted. They found refuge in remote areas, worked on ranches, and quietly maintained their traditions, language, and spiritual practices, often in secret. Families held onto fragments of their heritage, passing down stories, songs, and knowledge through generations.

The 20th century brought renewed hope and opportunities for self-determination. In 1901, the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians was officially recognized and granted a small reservation, a crucial step in preserving their identity and sovereignty. The latter half of the century saw a powerful resurgence of cultural pride and revitalization efforts.

Today, the Chumash are actively engaged in reclaiming and celebrating their heritage. The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, the only federally recognized Chumash tribe, has been a leading force in this movement. They have established robust programs for language revitalization, seeking to teach the Ventureño, Barbareño, and Ineseño dialects to younger generations. Traditional arts, such as basket weaving, shell bead making, and the construction of the tomol, have experienced a remarkable revival. The tribe has even undertaken several successful ocean crossings in replica tomols, recreating the journeys of their ancestors and symbolizing their enduring connection to the sea.

"Our ancestors endured unimaginable hardship, but they kept the flicker of our culture alive," says a contemporary Chumash elder. "Today, we fan that flicker into a flame for future generations. We are still here, our language is returning, our ceremonies are vibrant, and our connection to this land and sea remains unbroken."

Economically, the Santa Ynez Band has achieved significant success through ventures like the Chumash Casino Resort, which has provided resources for tribal services, education, healthcare, and cultural preservation initiatives. This economic independence has been vital in empowering the tribe to exercise its sovereignty and shape its own future.

The legacy of the Chumash is not confined to history books or museum exhibits. It is alive in the coastal winds, the rhythm of the waves, and the vibrant cultural resurgence of its people. From the ancient pathways of the tomol to the modern endeavors of self-determination, the Chumash story is a testament to the enduring power of culture, the resilience of the human spirit, and the unbreakable bond between a people and their ancestral land. Their journey continues, a powerful echo across the centuries, reminding us of the rich tapestry of California’s past and the vibrant presence of its first inhabitants.