Echoes of Conflict: The Cheyenne and Arapaho’s Enduring Struggle for Survival

For centuries, the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples commanded the vast expanse of the Great Plains, their lives intricately woven with the rhythms of the land, the migrations of the buffalo, and a profound spiritual connection to their ancestral territories. These two distinct but closely allied nations, known for their equestrian prowess, sophisticated social structures, and fierce spirit of independence, thrived across what is now Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. Yet, their rich history is also deeply marked by a prolonged and often brutal series of conflicts, primarily with the encroaching United States, a struggle for land, sovereignty, and the very right to exist that profoundly shaped their destinies and continues to resonate today.

The roots of these conflicts lie in the inexorable tide of American westward expansion, fueled by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and the relentless pursuit of resources. Before the mid-19th century, interactions with Euro-Americans were largely characterized by trade. However, as the 1840s and 1850s saw a surge in emigrant trails – the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe trails – cutting through prime Cheyenne and Arapaho hunting grounds, the stage was set for collision. The buffalo herds, the lifeblood of the Plains tribes, began to dwindle under the pressure of settler hunting and habitat fragmentation.

The Broken Promises of Fort Laramie (1851)

The first major attempt by the U.S. government to formalize relations and define territories was the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. This landmark agreement recognized vast lands for the Cheyenne and Arapaho, stretching from the North Platte River south to the Arkansas River, and from the Rocky Mountains eastward across the plains. In return, the tribes agreed to allow safe passage for emigrants and to permit the construction of roads and military posts. For a brief period, it seemed a semblance of peace might be possible.

However, this peace was fragile and short-lived. The ink was barely dry on the treaty when its provisions began to unravel. The discovery of gold in the Rocky Mountains in 1858-59, particularly during the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, triggered an unprecedented influx of prospectors and settlers into the heart of Cheyenne and Arapaho lands, directly violating the 1851 treaty. Mining camps and nascent towns sprang up overnight, polluting waterways, decimating game, and introducing disease.

The "Sell or Starve" Treaty of Fort Wise (1861)

The U.S. government’s response to the escalating tensions was not to enforce its own treaty, but to demand more land from the tribes. In 1861, a delegation of Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders, including the renowned peace chief Black Kettle, was coerced into signing the Treaty of Fort Wise. Under immense pressure, facing starvation and the overwhelming might of the U.S. military, they ceded all their vast 1851 territory, reserving only a small, barren tract along Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. Many influential chiefs, particularly the militant Dog Soldiers, a Cheyenne warrior society, rejected this treaty, arguing that the signers did not represent the entire nation. This division sowed further discord and laid the groundwork for future bloodshed.

Sand Creek: A Massacre, Not a Battle (1864)

The Fort Wise Treaty failed to alleviate tensions. Raids and counter-raids between desperate Native warriors and aggressive settlers and soldiers escalated. In the spring and summer of 1864, amidst a climate of fear and racial hatred fomented by figures like Colorado Territorial Governor John Evans and Colonel John M. Chivington, a Methodist minister turned military commander, peace efforts were initiated. Black Kettle, believing he had secured a promise of safety, moved his village, consisting of about 500 Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho, mostly women, children, and elderly, to the designated Sand Creek reserve, flying both an American flag and a white flag of truce over his lodge.

On the morning of November 29, 1864, Chivington, with a force of 700 volunteer soldiers, launched a brutal, unprovoked attack on the sleeping village. Despite the flags of peace, the troops indiscriminately murdered and mutilated over 150 Native Americans. The vast majority were women and children. Chivington’s chilling declaration, "Nits make lice," encapsulated the genocidal intent. The Sand Creek Massacre was a turning point, shattering any remaining trust between the Plains tribes and the U.S. government and igniting a broader, more brutal period of warfare across the central and southern plains.

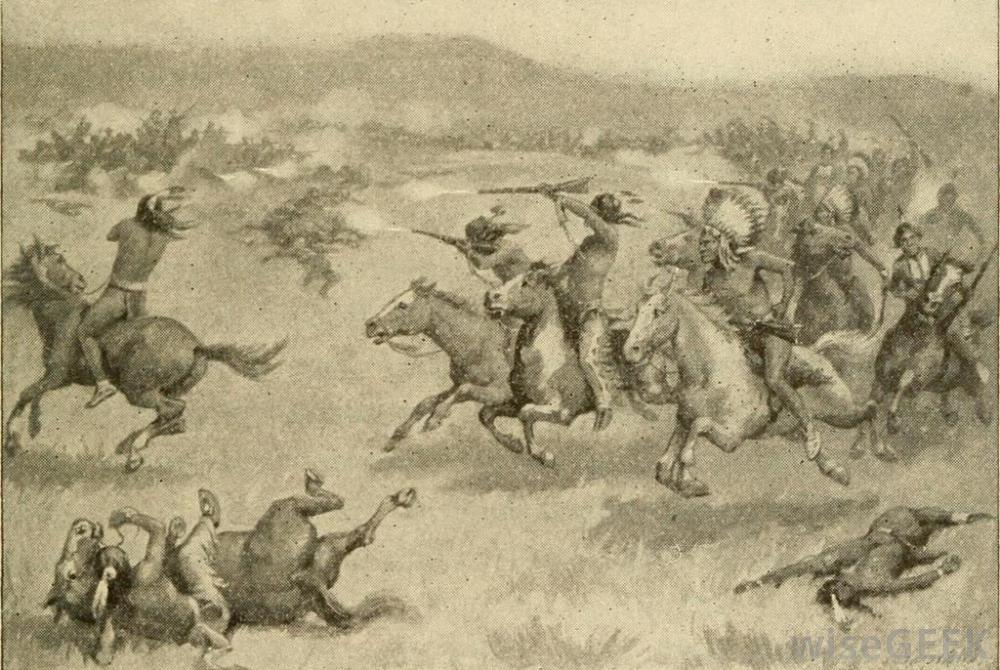

The Plains Wars Intensify: Retaliation and Further Bloodshed

The atrocities of Sand Creek galvanized the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and their allies, particularly the Lakota and Kiowa. The survivors recounted horrific tales, fueling a desperate desire for revenge and solidifying a resolve to resist. Over the next decade, the Central and Southern Plains became a battleground.

One notable engagement was the Battle of Beecher Island in September 1868, where a small force of U.S. Army scouts under Major George Forsyth was besieged by a much larger force of Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota warriors. Among the Native leaders was the legendary Cheyenne warrior Roman Nose, whose reputation for invincibility was widely known. Tragically, Roman Nose was killed during the battle, a devastating loss for the Cheyenne.

Just two months later, in November 1868, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry attacked Black Kettle’s Southern Cheyenne village on the Washita River in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). In a cruel echo of Sand Creek, Black Kettle, still advocating for peace, was among the estimated 100-150 Cheyenne killed, again mostly women and children. This event, known as the Battle of Washita, effectively ended the Southern Cheyenne’s capacity for large-scale armed resistance.

The Dog Soldiers, the militant Cheyenne warrior society, continued their fierce resistance. Their leader, Tall Bull, was killed in the Battle of Summit Springs in July 1869 by U.S. Army forces under Major Eugene Carr, marking a significant blow to the Cheyenne’s ability to coordinate large-scale attacks.

By the early 1870s, the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho, along with the Kiowa and Comanche, were increasingly confined to reservations in Indian Territory, their traditional way of life eradicated by the destruction of the buffalo herds and relentless military pressure. The Red River War (1874-1875) was the final major military campaign against these tribes, ending their freedom and forcing them onto reservations, where they faced disease, starvation, and the systematic dismantling of their culture.

The Northern Cheyenne’s "Flight for Freedom" (1878-1879)

While the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho endured their struggles, their northern relatives faced similar pressures. Following the Great Sioux War of 1876, which included the Battle of Little Bighorn where Cheyenne warriors fought alongside the Lakota against Custer, the Northern Cheyenne were forced to relocate from their homelands in Montana and Wyoming to the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation in Indian Territory. The conditions there were dire: unfamiliar climate, disease, and corrupt agents.

In September 1878, a group of approximately 300 Northern Cheyenne, led by chiefs Dull Knife and Little Wolf, embarked on a desperate, heroic journey, breaking out of the reservation and attempting to return to their ancestral lands in the North. This epic "Flight for Freedom" or "Dull Knife’s Breakout" covered over 1,500 miles, battling starvation, harsh weather, and relentless pursuit by thousands of U.S. soldiers.

Despite their incredible resilience and tactical brilliance, the journey was marked by tragedy. A portion of the group, led by Dull Knife, surrendered at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in January 1879, believing they would be allowed to remain in the North. Instead, they were ordered back to Indian Territory. When they refused, they were confined to unheated barracks without food or water for days. In a desperate attempt to break out, many were massacred by soldiers, including women and children. This horrific event, the Fort Robinson Massacre, stands as another stark reminder of the brutality inherent in the U.S. policy towards Native Americans. Little Wolf’s group, meanwhile, managed to reach Montana, eventually surrendering and being granted a small reservation there, a rare victory in a long history of defeat.

The Enduring Legacy

The history of conflicts endured by the Cheyenne and Arapaho is a poignant narrative of resistance, resilience, and immense loss. Their struggles were not simply against an invading army, but against a worldview that sought to erase their culture, seize their lands, and deny their very humanity. The destruction of the buffalo, the broken treaties, the massacres at Sand Creek, Washita, and Fort Robinson, and the forced assimilation policies left indelible scars.

Yet, despite these profound traumas, the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples have endured. They have maintained their cultural identity, language, and spiritual traditions, often in the face of overwhelming odds. Today, the Northern Cheyenne Nation in Montana and the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma continue to thrive, asserting their sovereignty, reviving their languages, and honoring the memory of their ancestors who fought so valiantly for their freedom and heritage. Their history serves as a vital reminder of the costs of westward expansion and the enduring strength of indigenous peoples in the face of adversity. The echoes of those conflicts still resonate, demanding that their story be told, understood, and never forgotten.