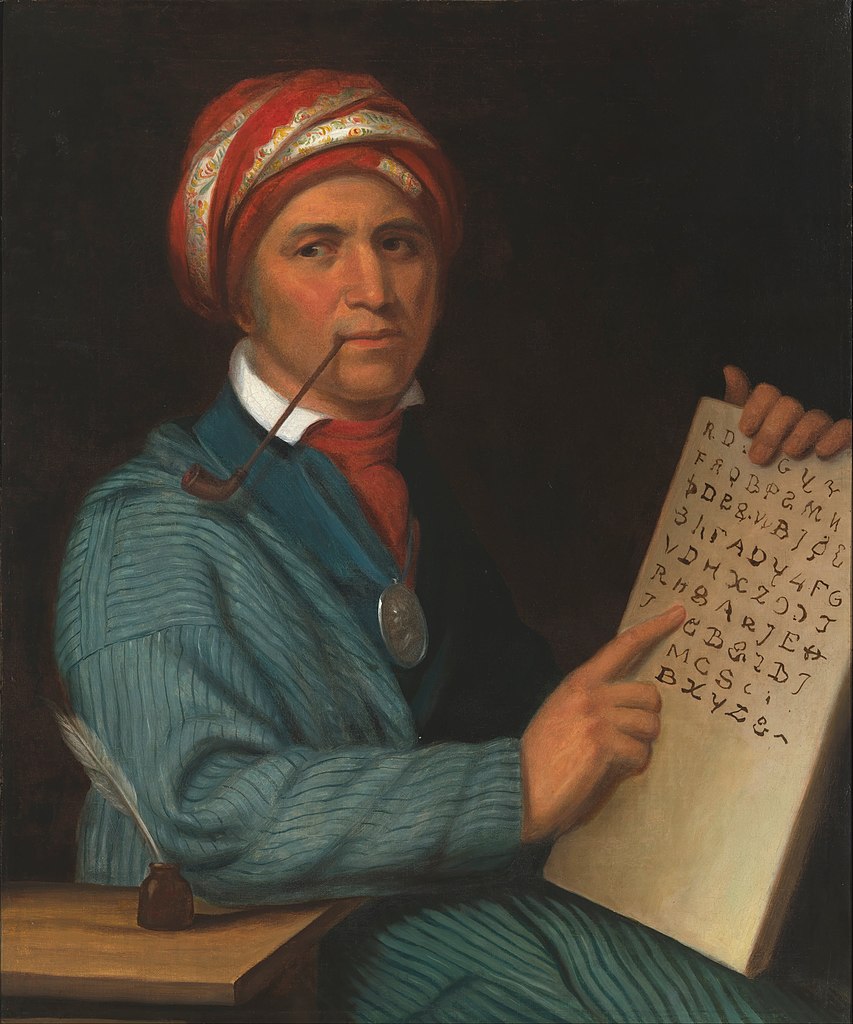

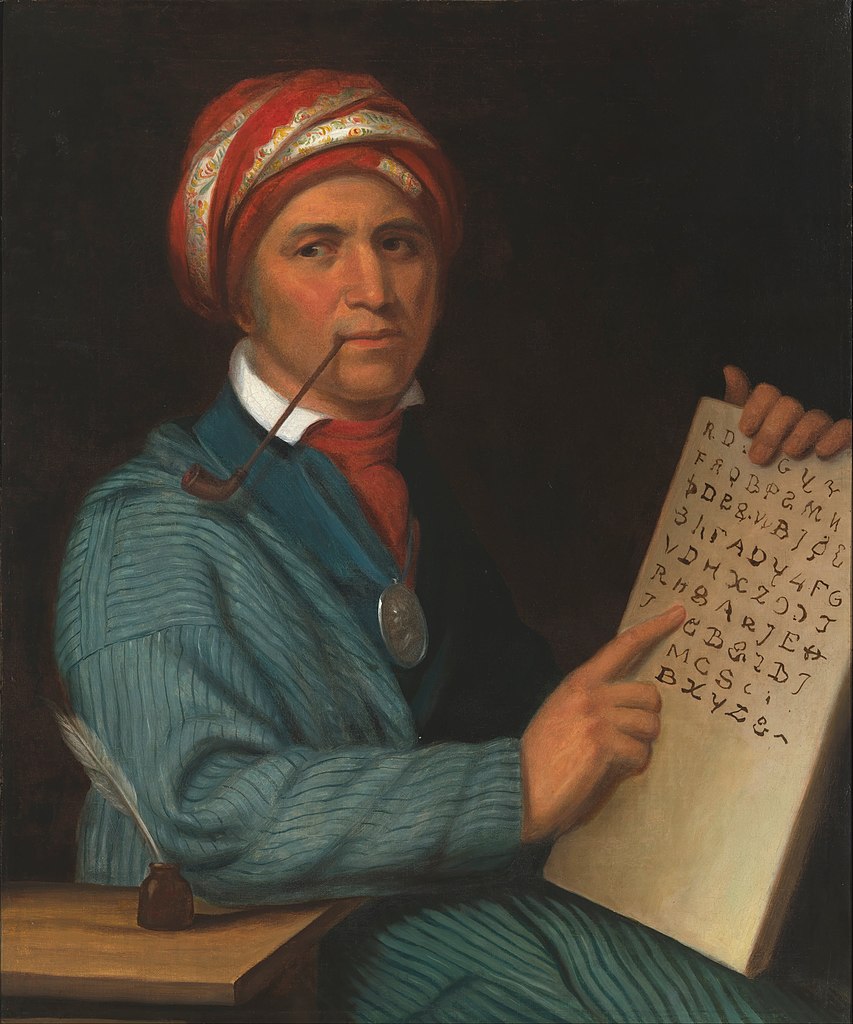

The Silent Revolution: Sequoyah and the Unlocking of a Nation’s Voice

In the annals of human endeavor, few individuals single-handedly spark a revolution as profound and far-reaching as the one ignited by Sequoyah, the Cherokee silversmith who, despite being illiterate himself, gifted his nation the power of written communication. Born around 1770 in Tuskegee, Tennessee, to a Cherokee mother and a white father, Sequoyah (also known by his English name, George Gist or Guess) embarked on a solitary, twelve-year quest that would forever alter the destiny of the Cherokee people, transforming them from an oral tradition into one of the most literate indigenous nations in the world. His creation, the Cherokee Syllabary, was not merely a writing system; it was a beacon of self-determination, a bulwark against cultural assimilation, and a testament to the extraordinary capacity of the human spirit.

The early 19th century was a tumultuous period for the Cherokee Nation. American expansionism was relentless, driven by the insatiable demand for land and the prevailing belief in Manifest Destiny. Treaties, often negotiated under duress and rarely honored, chipped away at ancestral lands. The Cherokee, a sophisticated society with a well-developed political structure, observed with growing apprehension the power that white settlers derived from their "talking leaves"—written documents that conveyed complex ideas, recorded laws, and formalized agreements. To the Cherokee, unable to read or write English, these documents were mysterious, their contents often twisted or misunderstood, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.

Sequoyah, a man of quiet observation and deep intellect, recognized this critical disparity. He saw firsthand how the inability to communicate in writing placed his people at a profound disadvantage. He witnessed the frustration of Cherokee leaders who struggled to negotiate with American officials, their spoken words often lost in translation or deliberately misrepresented. This pressing need for written communication became his singular obsession. "It is a shame," he is said to have remarked, "that our people cannot write."

Driven by this conviction, Sequoyah began his monumental task around 1809. He had no formal education, no models of linguistics to guide him, and no knowledge of other writing systems beyond observing the English alphabet. His initial attempts were rudimentary, focused on creating a symbol for each word, much like ancient hieroglyphics. He filled countless pages with these pictographs, only to realize the impracticality of such a system for a complex language like Cherokee, which could have tens of thousands of words. This early setback, however, did not deter him. It only sharpened his focus.

Sequoyah then made his pivotal breakthrough: he realized that the key lay not in representing entire words, but in representing the syllables that made up those words. The Cherokee language, like many others, is structured around a relatively small number of distinct syllables. After years of painstaking analysis, listening intently to the sounds of his language, he distilled the complex tapestry of Cherokee speech into 85 (initially 86) distinct phonetic symbols. Each symbol represented a single syllable, such as "ga," "ho," or "tsu." This was a stroke of genius. Unlike the English alphabet, which requires mastery of 26 letters and countless irregular spellings, Sequoyah’s syllabary was remarkably straightforward and logical.

The symbols themselves were often inspired by English letters he had seen in books or on signs, but their sounds bore no relation to their English counterparts. For example, his symbol for "a" resembled the English "D," and his symbol for "go" looked like an "M." This clever appropriation meant that while the visual form might be familiar, the phonetic value was entirely new and specific to Cherokee, making it a truly indigenous creation.

His dedication during these years was extraordinary. He worked in isolation, often ridiculed by his neighbors who considered his efforts a strange and futile obsession. His own wife, frustrated by his apparent neglect of his silversmithing trade and convinced he was dabbling in witchcraft, reportedly burned his early notes and models. Yet, Sequoyah persevered, refining his system, meticulously documenting each sound and its corresponding symbol.

The moment of triumph arrived in 1821. Sequoyah presented his syllabary to the Cherokee tribal council. To demonstrate its efficacy, he taught his young daughter, Ayoka, to read and write using his system. Ayoka, after only a few days of instruction, could flawlessly exchange written messages with her father, proving the ease and efficiency of the syllabary. The council, initially skeptical, was astonished. They witnessed a tangible manifestation of power that rivaled the "talking leaves" of the white man. The news spread like wildfire.

The adoption of the Syllabary was nothing short of miraculous. Within months, thousands of Cherokee people, young and old, learned to read and write. Missionaries observed that Cherokees could achieve literacy in their own language in a matter of weeks, a feat that took years for English speakers. The speed and universality of its adoption were unprecedented.

The impact was immediate and transformative. In 1828, just seven years after its introduction, the Cherokee Nation began publishing its own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix (or Tsalagi Tsulehisanvhi), a bilingual publication printed in both Cherokee and English. Edited by Elias Boudinot, a prominent Cherokee leader, the Phoenix became a vital tool for communicating news, laws, and national policy, fostering a strong sense of national identity and unity.

Beyond the newspaper, the Syllabary revolutionized education, allowing the Cherokee to establish schools and print books in their own language. It enabled the codification of their laws, leading to the creation of the Cherokee Constitution in 1827, a remarkable document that established a republican form of government with executive, legislative, and judicial branches, mirroring the structure of the United States. This written constitution served as a powerful declaration of sovereignty and self-governance.

More profoundly, the Syllabary became a shield against the relentless pressure of cultural assimilation. It allowed the Cherokee to preserve their rich oral traditions, their history, and their spiritual beliefs in written form. It gave them a voice, not just within their own nation, but to the outside world, enabling them to articulate their grievances and assert their rights in the face of forced removals and land seizures. During the tragic Trail of Tears in 1838, when the Cherokee were forcibly marched from their ancestral lands to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), the Syllabary provided a means for them to document their suffering, to maintain hope, and to rebuild their society once they arrived.

Sequoyah’s achievement transcended the Cherokee Nation. His syllabary inspired other indigenous language groups, such as the Cree and Ojibwe, to develop their own writing systems, often based on his phonetic principles. He became a symbol of intellectual prowess and resilience, demonstrating that indigenous peoples possessed the capacity to innovate and adapt on their own terms.

Sequoyah himself continued his work, traveling west to seek out other Cherokee groups who had migrated earlier, hoping to share his gift with them. He died around 1843, likely in present-day Mexico, while on a journey to find lost bands of Cherokee. His legacy, however, remains vibrant and enduring.

Today, the Cherokee Syllabary is still taught and used, a living testament to Sequoyah’s genius. It serves as a powerful reminder of a time when one man, without formal education or external assistance, changed the course of his nation’s history. Sequoyah did not wield a sword or command an army; he wielded the power of an idea, unlocking the potential for literacy and self-expression, and in doing so, he preserved the soul of a nation. His silent revolution continues to echo, a testament to the transformative power of language and the indomitable spirit of those who seek to empower their people.