The Enduring Echoes of the "Trail of Tears": A Cherokee Nation History of Removal

The story of the Cherokee Nation’s removal from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States is a stark, painful chapter in American history, a narrative etched in the national consciousness as the "Trail of Tears." It is a story not merely of displacement, but of broken treaties, legal battles, political maneuvering, and an unimaginable human cost that continues to resonate through generations. Far from a simple relocation, it was a forced exodus that fundamentally reshaped the identity and destiny of a sovereign people, leaving an indelible stain on the fabric of the young American republic.

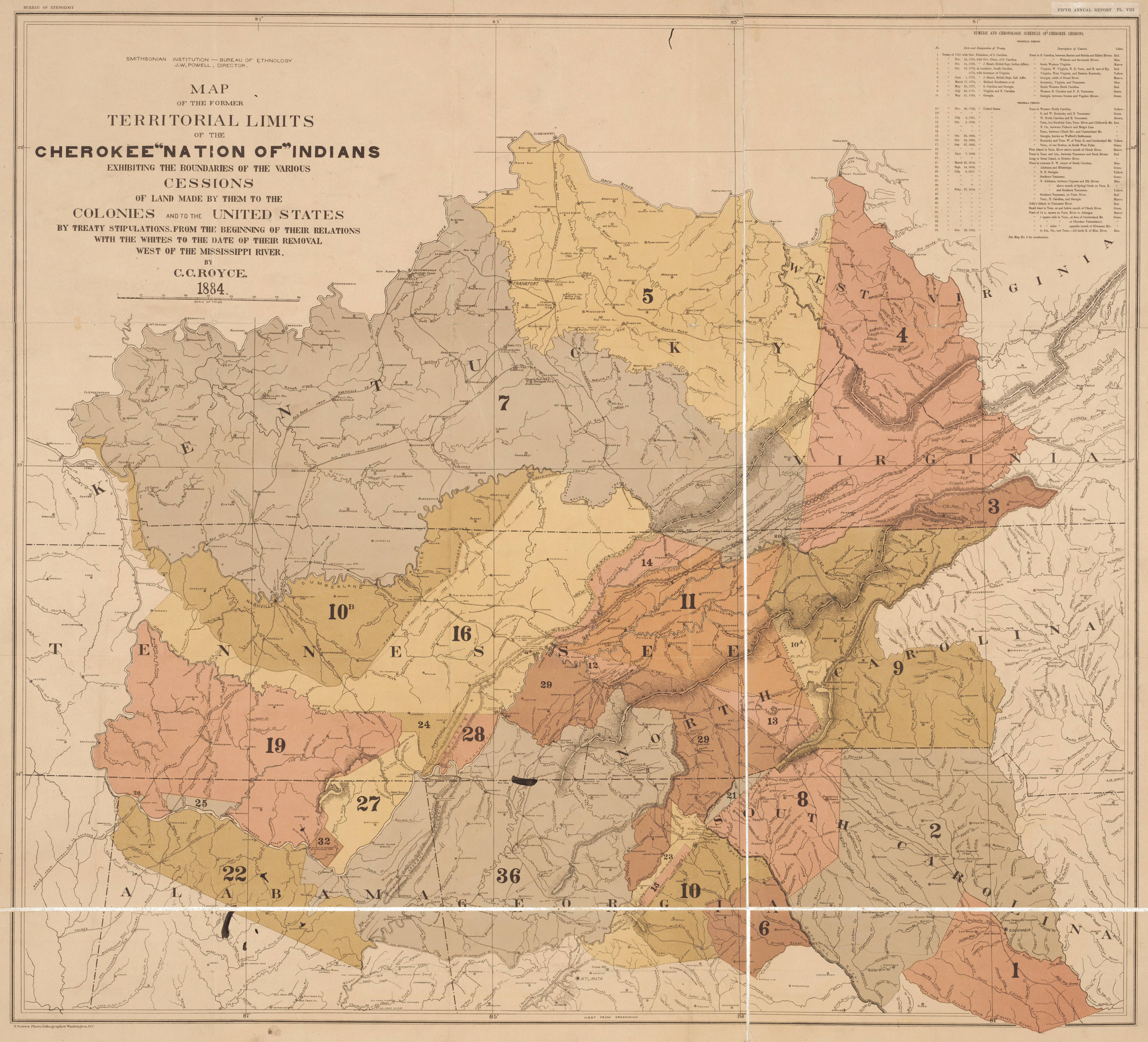

For centuries before the arrival of European settlers, the Cherokee people inhabited a vast, fertile territory spanning parts of present-day Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, and South Carolina. They were not nomadic hunter-gatherers but an established, agricultural society with sophisticated social, political, and cultural structures. By the early 19th century, the Cherokee had embraced many aspects of American society, not out of weakness, but out of a pragmatic desire to coexist and protect their sovereignty. They adopted a written constitution in 1827, modeled after the U.S. Constitution, established a bicameral legislature, and developed a thriving economy with farms, schools, and even a newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, published in both English and the Cherokee syllabary invented by Sequoyah. This remarkable innovation, allowing instant literacy in their native tongue, stands as a testament to their advanced civilization and intellectual prowess.

This era of adaptation and self-governance, however, coincided with an escalating tide of American expansionism, fueled by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and an insatiable hunger for land. The primary catalyst for the Cherokee’s ultimate removal was the discovery of gold in their ancestral lands near Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1829. This discovery triggered a gold rush, leading to an influx of white prospectors and a desperate push by the state of Georgia to claim Cherokee territory. Despite numerous treaties explicitly recognizing Cherokee sovereignty and land rights, Georgia began to assert its jurisdiction over Cherokee lands, distributing them to white settlers through a land lottery.

At the heart of the federal government’s policy was President Andrew Jackson, a revered military hero but also a staunch proponent of "Indian Removal." Jackson, who had personally fought against Native American tribes in the past, believed that the "progress" of the white nation necessitated the relocation of Indigenous peoples beyond the Mississippi River. His administration pushed through the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which, while ostensibly offering "exchanges" of land, was widely understood as a tool for forced displacement. Jackson articulated his view in his 1830 message to Congress, arguing that removal would "enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions." This paternalistic view completely disregarded the Cherokee’s established and "un-rude" institutions, viewing their distinct culture as an impediment to American progress.

The Cherokee Nation, led by its Principal Chief John Ross, refused to passively accept this fate. They chose the path of legal and political resistance, appealing to the very laws and institutions of the United States. This led to two landmark Supreme Court cases. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Chief Justice John Marshall, while acknowledging the Cherokee’s unique status, ruled that they were a "domestic dependent nation" and thus did not have the standing to sue the state of Georgia directly. However, in the subsequent case, Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court sided squarely with the Cherokee, ruling that Georgia’s laws had no force within Cherokee boundaries and that the Cherokee Nation was a sovereign entity.

This was a profound victory for the Cherokee, a clear affirmation of their rights by the highest court in the land. Yet, it was a hollow triumph. President Jackson famously defied the ruling, reportedly stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." With the federal government refusing to uphold the law, the Cherokee’s legal victory became practically meaningless, leaving them vulnerable to Georgia’s escalating encroachments.

Amidst this desperate struggle, a tragic internal division emerged within the Cherokee Nation. A minority faction, known as the Treaty Party, led by prominent figures such as Major Ridge, Elias Boudinot (the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix), and Stand Watie, grew convinced that further resistance was futile. They believed that the federal and state governments would ultimately prevail and that the best course of action was to negotiate a removal treaty to secure some concessions for their people. This conviction, born out of despair and a pragmatic assessment of their grim options, put them in direct opposition to Principal Chief John Ross and the vast majority of the Cherokee Nation, who remained steadfast in their refusal to cede their ancestral lands.

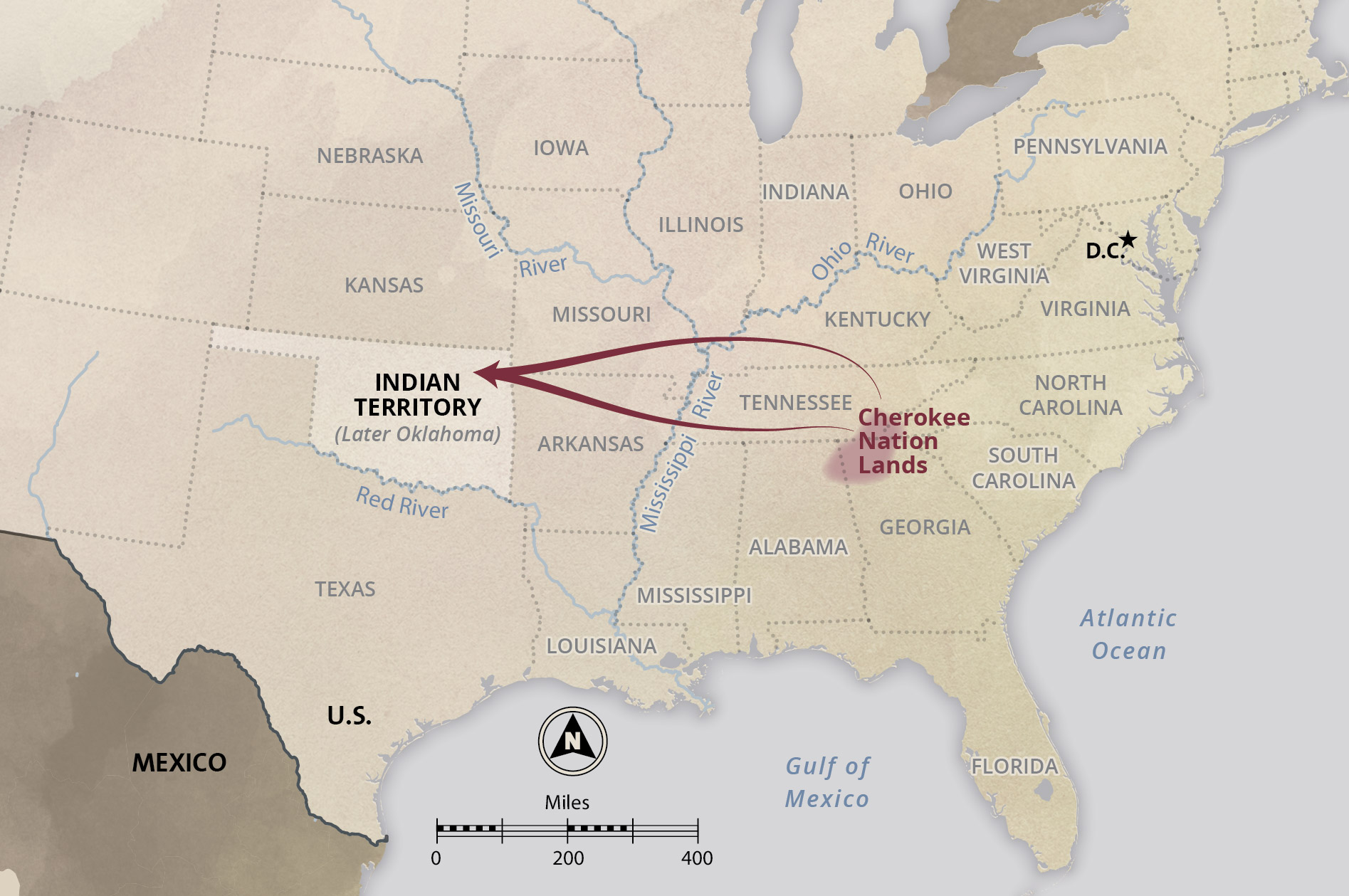

In December 1835, without the authority of the Cherokee Nation’s legitimate government, the Treaty Party signed the Treaty of New Echota with the U.S. government. This treaty purported to exchange all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi for five million dollars and a tract of land in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). John Ross and over 15,000 Cherokees immediately denounced the treaty as fraudulent and illegitimate, protesting that it was signed by a small, unauthorized minority and did not represent the will of the nation. Despite these vehement protests, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty by a single vote, and President Jackson declared it binding. The Cherokee were given two years to voluntarily emigrate.

As the May 1838 deadline approached, fewer than 2,000 Cherokees had moved west. The U.S. government, under President Martin Van Buren (Jackson’s successor), then ordered the military to enforce the removal. General Winfield Scott was put in charge of the operation, commanding approximately 7,000 U.S. soldiers and state militia. In the spring and summer of 1838, these troops began the brutal process of rounding up the Cherokee people.

Homes were invaded, families were separated, and people were forcibly dragged from their fields, their dinners, and their beds. They were given little time to gather their belongings, often losing everything they owned. "The soldiers came and took us from our homes," recalled one survivor, "many of our people were not allowed to take anything with them, not even a blanket." The Cherokees were then confined in stockades and internment camps, often in unsanitary and overcrowded conditions, awaiting the forced march. Disease, particularly dysentery and whooping cough, quickly spread through these camps, claiming the lives of many, especially the young and the elderly.

The forced march, which began in the fall of 1838 and continued through the brutal winter of 1838-1839, became known as the "Trail of Tears" (Nunna daul Isunyi in Cherokee, meaning "the place where they cried"). Approximately 16,000 Cherokees were forced to walk over 1,000 miles, often barefoot, through harsh weather conditions. They were poorly clothed, inadequately fed, and denied proper medical care. The journey was a relentless ordeal of suffering, exposure, starvation, and disease. It is estimated that over 4,000 Cherokee men, women, and children died during the removal—a quarter of their entire population. Their suffering was immense, as recounted by a soldier who witnessed the march: "I fought through the War Between the States and have seen many men shot, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew."

Upon arrival in Indian Territory, the survivors faced the daunting task of rebuilding their lives in an unfamiliar landscape, often in conflict with other relocated tribes. The internal divisions caused by the Treaty of New Echota also led to further violence, including the assassinations of Major Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and John Ridge in 1839, tragically highlighting the deep wounds inflicted by the removal policy.

The "Trail of Tears" remains a profound and enduring wound in the collective memory of the Cherokee Nation and a stark reminder of the injustices perpetrated against Indigenous peoples in the pursuit of American expansion. It is a story that compels us to confront the complexities of national identity, the abuse of power, and the devastating consequences of racism and land greed.

Today, the Cherokee Nation is the largest of the federally recognized Cherokee tribes, a vibrant and sovereign nation with a population exceeding 450,000 citizens. They have rebuilt, thrived, and continue to honor their ancestors’ sacrifices by preserving their language, culture, and traditions, while also engaging actively in modern political and economic life. The legacy of the "Trail of Tears" is not one of defeat, but of resilience, survival, and an unyielding determination to maintain their identity and sovereignty. It stands as a powerful testament to the human spirit’s ability to endure unimaginable hardship and serves as a vital lesson for understanding the true cost of unchecked ambition and the enduring importance of justice and treaty obligations. The echoes of those mournful footsteps across the "Trail of Tears" continue to call for remembrance, reconciliation, and a deeper understanding of America’s shared, complex history.