Beyond Fabric and Form: The Profound Language of Ceremonial Dress and Dance Outfits

More than mere garments, ceremonial dress and dance outfits are living tapestries woven from history, identity, and spirituality. They are not merely adornments but powerful conduits of meaning, encapsulating centuries of tradition, belief, and collective memory. Across cultures and continents, these ensembles transform the wearer, communicate complex narratives, and bridge the earthly with the divine, making them indispensable elements of human ritual and performance.

The profound significance of these outfits lies in their ability to transcend the mundane. They mark transitions, celebrate milestones, invoke spirits, and recount epic tales. Every stitch, every bead, every feather is a deliberate choice, imbued with a specific purpose and echoing a rich cultural lexicon. To understand these garments is to peer into the very soul of a people, to decipher their worldview, their values, and their relationship with the cosmos.

The Fabric of Identity and Spirituality

At their core, ceremonial attire and dance costumes are declarations of identity. They speak of lineage, status, community belonging, and often, a connection to the sacred. For many Indigenous cultures, regalia is not simply worn; it is an extension of the self, imbued with spiritual power. The Lakota people, for instance, consider their ceremonial dress, particularly that worn for the Sun Dance or Pow Wows, to be deeply sacred. Eagle feathers, a common element, are not merely decorative but symbolize strength, honor, and a direct connection to the Creator and the spirit world. Each feather is earned, carrying a story of personal achievement or ancestral legacy. As one elder articulated, "These are not costumes; they are our identity woven into cloth, a prayer made visible."

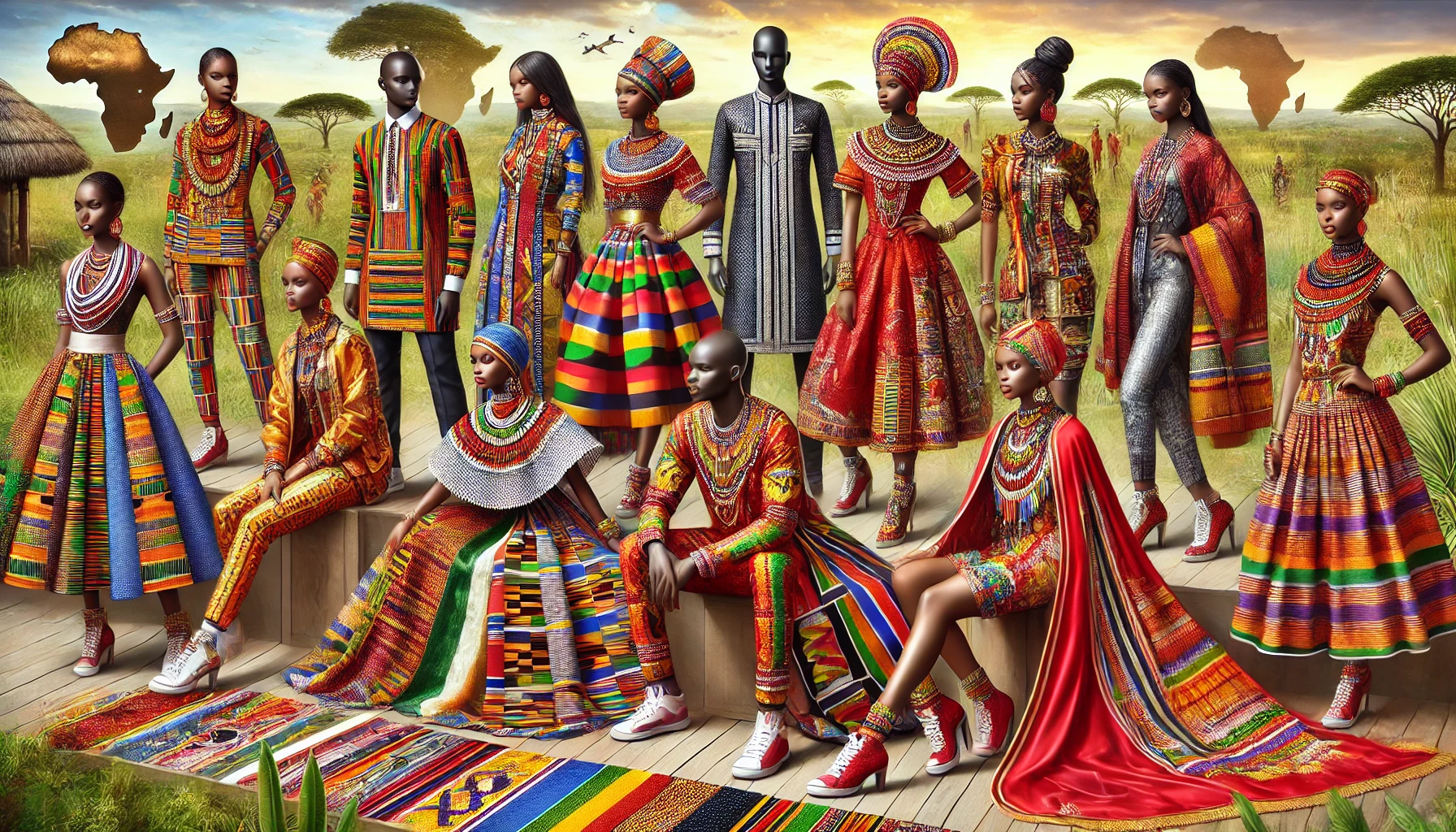

Similarly, in many African traditions, ceremonial dress signifies a person’s role within the community, their age grade, or their spiritual calling. The vibrant beadwork of the Maasai in East Africa, for example, conveys marital status, wealth, and social standing, with intricate patterns and color combinations holding specific meanings understood by the community. Red often symbolizes bravery and the blood of cattle, while blue represents the sky and God. These garments are not just worn; they are lived in, becoming part of the individual’s spiritual and social fabric.

A Symphony of Symbols: Components and Their Meanings

The constituent elements of ceremonial outfits are rarely arbitrary. Each material, color, and embellishment contributes to a complex semiotic system:

-

Colors: Color symbolism is nearly universal yet profoundly specific to each culture.

- Red: Often signifies life, blood, passion, war, power, and protection. In many Asian cultures, red is associated with good fortune and is a predominant color in wedding attire.

- White: Commonly represents purity, peace, death, and spiritual transcendence. In some African contexts, white is linked to ancestors and the spirit realm.

- Blue: Symbolizes the sky, water, fertility, and divinity in numerous traditions, from the ancient Egyptians to various Hindu deities.

- Black: Can denote mourning, mystery, wisdom, or the earth, depending on the cultural context.

- Yellow/Gold: Often associated with the sun, wealth, prosperity, and royalty, seen in imperial robes in China or the opulent attire of various monarchies.

-

Materials: The very fabric and adornments carry deep meaning.

- Feathers: Especially prominent in Indigenous American cultures, feathers (particularly eagle feathers) represent connection to the spirit world, honor, courage, and spiritual protection. In Polynesian traditions, bird feathers were reserved for royalty, symbolizing divinity and high status.

- Animal Skins/Furs: Often signify a connection to the animal kingdom, embodying the strength, cunning, or spiritual essence of the animal. In Siberian shamanic traditions, animal skins aid in spiritual journeys, allowing the shaman to embody the animal’s spirit.

- Beads/Shells: Beads are often miniature repositories of history and status. In West African and Native American cultures, intricate beadwork can tell stories, denote clan affiliation, or signify wealth and social standing. Cowrie shells, once a form of currency, symbolize fertility, prosperity, and protection in many African and Oceanic cultures.

- Metals (Gold, Silver, Copper): Frequently used to denote wealth, power, and divine connection. Gold often links to the sun and divinity, while silver is associated with the moon and purity.

- Plants/Fibers: Natural fibers like raffia, cotton, or bark cloth often connect the wearer to the earth and local environment. Hawaiian hula skirts made from ti leaves or raffia skirts in Pacific Island dances are direct expressions of their natural surroundings.

-

Embellishments and Form:

- Masks: Perhaps the most transformative element, masks are used to conceal identity and embody spirits, ancestors, or deities. In West African masquerades (like the Egungun or Gelede), masks are not merely representations but are believed to become the spirit itself, facilitating communication between the living and the dead.

- Bells and Rattles: Integrated into many dance outfits (e.g., flamenco dresses, Native American jingle dresses, or African ankle rattles), these produce rhythmic sounds that enhance the performance, mark the beat, and are often believed to ward off evil spirits or call benevolent ones.

- Headwear: Crowns, elaborate headdresses, and turbans frequently signify royalty, spiritual authority, or special status. The isicholo hat of Zulu women in South Africa, for instance, marks marital status and respect.

Rituals of Passage and Celebration

Ceremonial dress is inextricably linked to rites of passage, marking life’s significant transitions.

- Weddings: From the elaborate white gowns of Western brides to the vibrant red saris of Indian brides (symbolizing love, fertility, and prosperity) and the multi-layered kimonos of Japanese brides, wedding attire is universally designed to highlight the importance of the union and the transition into a new phase of life. The Kente cloth worn in Ghanaian weddings, with its intricate patterns and colors, tells stories of heritage and hopes for the couple.

- Initiations: For young men and women in many Indigenous societies, initiation ceremonies are crucial for transitioning to adulthood. The dress worn during these rituals often signifies a shedding of childhood and an assumption of new responsibilities. The Hamar people of Ethiopia, for example, have distinct ceremonial attire for their bull-jumping ceremony, a rite of passage for young men.

- Funerals: While often somber, funeral attire too is ceremonial, reflecting respect for the deceased and communal grief. The stark black of Western mourning dress, or the white worn in some Asian cultures, are deliberate choices communicating reverence and the gravity of the moment.

Performance and Protection: The Dance Outfits

Dance outfits, while often ceremonial, have additional functional and spiritual dimensions. They are designed for movement, to enhance the visual spectacle, and often, to channel specific energies or narratives.

- Balinese Barong Dance: The Barong, a lion-like creature representing good, is embodied by two dancers wearing an elaborate, heavy costume made of mirrors, feathers, and a fierce mask. The costume is not just an aesthetic choice; it is believed to house the spirit of the Barong, offering protection and balancing cosmic forces during the dance.

- Pow Wow Regalia: Native American Pow Wow dancers wear regalia that is both breathtakingly beautiful and functional. The feathers, beadwork, bells, and fringes move with the dancer, creating a mesmerizing spectacle of color and sound. Each piece contributes to the narrative of the dance, honoring ancestors, celebrating victories, or expressing gratitude. The jingle dress, with its hundreds of metal cones, creates a distinct sound believed to have healing properties.

- West African Masquerades: Dances featuring elaborate masks and full-body costumes, often made from raffia, cloth, and carved wood, are central to many West African rituals. The Egungun masquerade of the Yoruba people, for instance, involves dancers representing ancestral spirits, whose voluminous, flowing costumes are designed to create a visual and auditory spectacle that signifies their spiritual presence and power. The swirling fabric is believed to trap and disperse negative energies.

- Flamenco Dress: While perhaps less overtly spiritual in modern times, the traje de flamenca with its ruffles and vibrant colors, is designed to accentuate the passionate movements of the dancer, becoming an extension of their emotional expression and the rhythmic energy of the music.

Keepers of History and Heritage

Beyond their immediate ritualistic or performative function, ceremonial dress and dance outfits serve as vital archives of cultural heritage. They embody ancestral knowledge, passed down through generations of artisans, weavers, and performers. The techniques for crafting these garments – intricate beadwork, specific weaving patterns, dyeing processes – are often themselves traditions, preserving skills and stories that might otherwise be lost.

The continuity of these traditions is crucial for cultural survival. When a young person learns to sew their first piece of regalia, or to perform a dance in their ancestral attire, they are not just learning a craft or a sequence of steps; they are connecting with their heritage, reinforcing their identity, and ensuring the transmission of invaluable cultural knowledge to future generations. These garments are silent historians, speaking volumes about the journey of a people.

Challenges and Continuities

In the modern world, the traditions surrounding ceremonial dress and dance outfits face both challenges and opportunities. Globalisation, commercialisation, and cultural appropriation pose threats to the authenticity and sacredness of these garments. When traditional attire is mass-produced for tourist markets or adopted without understanding or respect by outsiders, its inherent meaning can be diluted or distorted.

However, there is also a resurgence of interest and pride in preserving these traditions. Communities are actively working to document, teach, and protect their unique forms of dress and dance. Museums and cultural institutions play a role in showcasing these garments, while community elders and artisans are dedicated to teaching younger generations the intricate skills and profound meanings behind each piece. Digital platforms also offer new avenues for sharing knowledge and fostering appreciation, albeit with careful consideration for cultural protocols.

Conclusion

Ceremonial dress and dance outfits are far more than mere embellishments; they are potent symbols, spiritual tools, and living chronicles of human experience. From the sacred feathers of a Native American chief to the vibrant saris of an Indian bride, the transformative masks of an African masquerade, or the flowing kimonos of a Japanese dancer, these garments articulate identity, honor tradition, and connect individuals to the broader tapestry of their culture and the cosmos. They remind us that the human desire to express, celebrate, and commune with the sacred is a universal language, beautifully and profoundly stitched into the very fabric of our being. As long as humanity seeks meaning, celebrates life, and remembers its past, these extraordinary outfits will continue to tell stories, evoke spirits, and weave the narrative of who we are.