Across the vast expanse of Turtle Island, a quiet crisis unfolds beneath the forest canopy and amidst sun-dappled fields. The iconic box turtle, a creature of ancient lineage and profound ecological significance, faces an uncertain future. For generations, these long-lived reptiles have navigated the complex tapestries of North America’s diverse ecosystems, their domed shells a familiar sight. Today, their populations are in decline, prompting a critical surge in scientific inquiry: box turtle population studies, a vital endeavor to understand, protect, and restore these cornerstone species.

For countless Indigenous nations, Turtle Island is not merely a geographic landmass but a living entity, the very foundation of creation myths and spiritual identity. The turtle, often depicted as carrying the world on its back, symbolizes longevity, wisdom, and resilience. This deep cultural reverence imbues the scientific effort with an added layer of urgency and respect, reminding researchers that their work is not just about numbers and data, but about the health of a sacred landscape and its interconnected inhabitants.

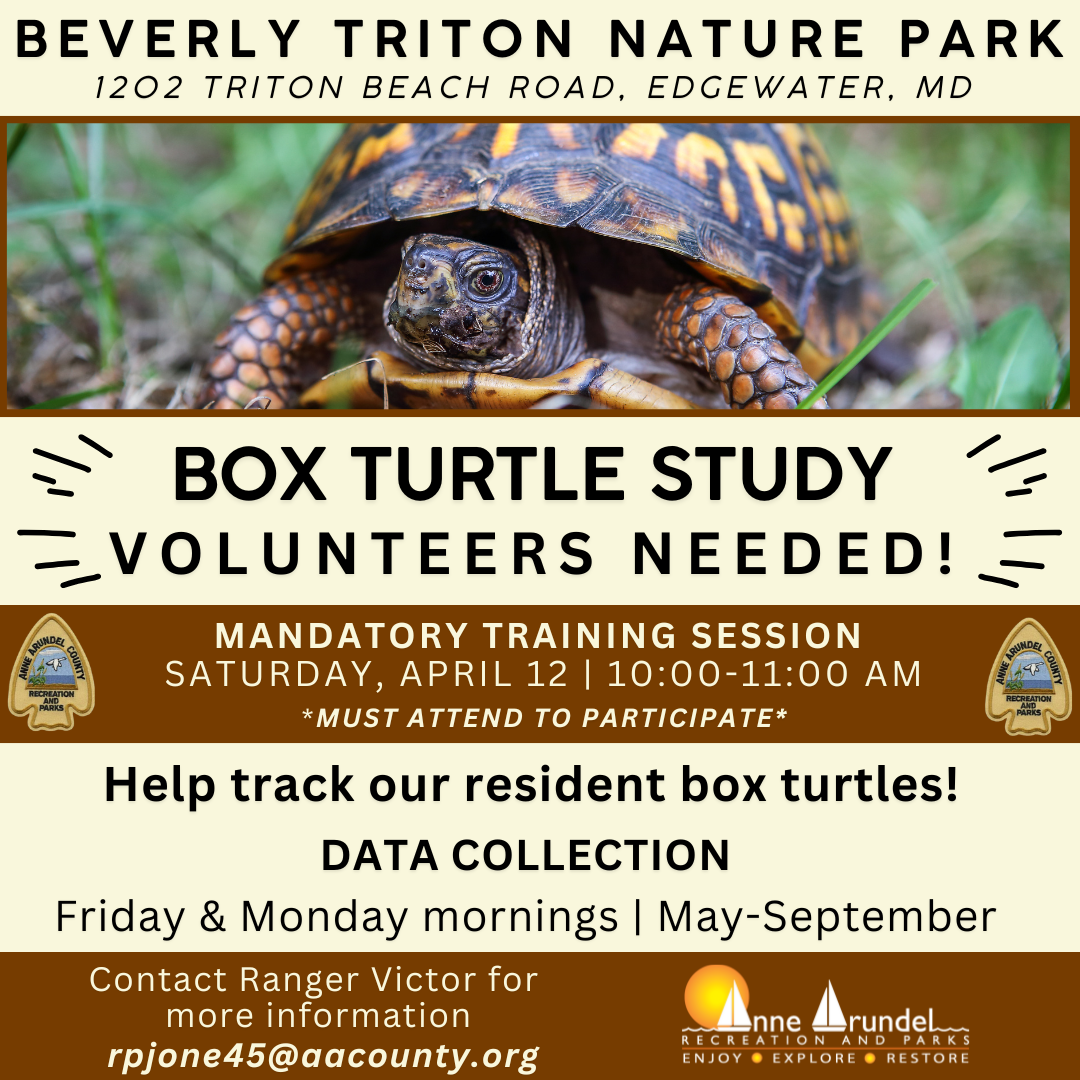

The Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina) and the Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata ornata) are perhaps the most recognized representatives of this genus across Turtle Island. Characterized by their highly domed carapaces and the unique ability to completely withdraw into their shells, these terrestrial turtles are remarkably long-lived, often exceeding 50 years, with some individuals documented to live over a century. However, this longevity comes at a cost: a slow reproductive rate, late sexual maturity (often 7-10 years), and small clutch sizes (typically 3-8 eggs) make them incredibly vulnerable to population declines. Once a population is impacted, recovery is painstakingly slow, often taking decades or even centuries.

The threats are manifold and pervasive. Habitat fragmentation, exacerbated by relentless development, slices through their ancestral territories, isolating populations and limiting genetic exchange. Road mortality is a significant killer, as turtles attempting to cross busy thoroughfares are often crushed. The illegal pet trade continues to siphon individuals from wild populations, particularly adult females, which are crucial for reproduction. Pesticide use, disease, and climate change further compound these pressures, altering habitats and disrupting natural cycles.

It is against this backdrop that box turtle population studies become indispensable. These ancient reptiles serve as crucial bioindicators, their health reflecting the overall ecological integrity of an ecosystem. Because of their small home ranges and long lives, they absorb and accumulate environmental toxins, making them living barometers of environmental quality. Understanding their population dynamics, therefore, provides insights not only into their own survival but into the broader health of the environments they inhabit.

The methodologies employed in these studies are diverse and often require a significant commitment of time, resources, and patience. One of the foundational techniques is mark-recapture. Researchers capture turtles, record their location, take measurements (carapace length, weight), assess their health, and uniquely mark them before releasing them back into the exact spot of capture. Marking methods vary but often involve notching the marginal scutes (the plates around the edge of the shell) in a specific, harmless pattern, or implanting Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tags, similar to microchips used for pets. Each notch is a silent identifier, allowing researchers to track individual turtles over years, even decades. Recaptures provide critical data on population size, survival rates, growth rates, and movement patterns. A low recapture rate over successive years in a previously stable area can be an early warning sign of decline.

Radio telemetry offers a more detailed look into the daily lives of box turtles. A small, lightweight radio transmitter is carefully affixed to the turtle’s carapace, often with epoxy, and is designed to fall off naturally after a year or two. Researchers then use directional antennas and receivers to track the turtles, sometimes daily, for months or even years. This allows them to map individual home ranges, identify critical habitats for foraging, basking, nesting, and overwintering, and observe behaviors such as mate-seeking or predator avoidance. Dr. Anya Sharma, a herpetologist at the University of the Great Lakes, explains, "Telemetry gives us an intimate understanding of their spatial ecology. We can see how they navigate fragmented landscapes, which corridors they use, and where they encounter the highest risks. This data is invaluable for land management decisions."

Genetic analysis has emerged as a powerful tool, complementing field studies. By collecting small, harmless tissue samples (e.g., from a shed scute or a tiny clip from a non-sensitive area), researchers can analyze DNA to determine genetic diversity, population connectivity, and the extent of inbreeding. Isolated populations, surrounded by human development, often exhibit low genetic diversity, making them more susceptible to disease and less adaptable to environmental changes. Genetic studies can pinpoint these vulnerable populations and inform strategies for maintaining genetic flow, such as creating wildlife corridors or even carefully planned translocations.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) play a crucial role in integrating and visualizing the vast amounts of spatial data collected. Researchers use GIS to map turtle sightings, home ranges, habitat types, roads, waterways, and areas of human development. This allows for the identification of critical habitats, mapping of movement corridors, and pinpointing areas of high risk, such as road crossings or areas prone to poaching. By layering these different datasets, conservationists can develop highly targeted strategies for habitat protection and restoration.

Perhaps the most challenging, yet most crucial, aspect of box turtle population studies is their long-term nature. Given the turtles’ longevity and slow life history, meaningful trends in population dynamics often only become apparent after many years, sometimes even decades, of consistent monitoring. "You can’t just study box turtles for a year or two and expect to understand their population trends," states Dr. Marcus Thorne, who has led a box turtle monitoring project in the Appalachian foothills for over 30 years. "Their lives unfold over such a long timescale. Decades-long commitments are not just desirable; they are imperative to truly grasp the impacts of environmental change and the effectiveness of conservation interventions." These long-term datasets are goldmines, revealing subtle shifts in demographics, survival, and reproduction that short-term studies would inevitably miss.

The challenges in conducting these studies are significant. Box turtles are often cryptic, blending seamlessly into their surroundings, making them difficult to find. The work is painstaking, often solitary, and requires dedication through all seasons. Funding for long-term ecological research can be sporadic, and public engagement, while vital, can be challenging in a world increasingly disconnected from nature.

However, the collaboration between scientific institutions, government agencies, and Indigenous communities offers a powerful path forward. Indigenous ecological knowledge, honed over millennia, provides invaluable insights into historical distribution, habitat use, and traditional stewardship practices that complement Western scientific approaches. Elder Thomas Blue Sky, a knowledge keeper from the Anishinaabe Nation, shares, "Our stories speak of the turtle’s resilience, but also of our responsibility to care for her. These studies, they are a way to listen to the land, to understand what she needs from us now." Partnerships that integrate both scientific rigor and traditional wisdom create more holistic and effective conservation strategies.

The data gathered from these painstaking studies are not ends in themselves but vital tools for action. They inform habitat restoration projects, guiding where to plant native vegetation, create basking sites, or establish protected nesting areas. They pinpoint critical road crossings where wildlife underpasses or exclusion fencing can drastically reduce mortality. They provide the evidence needed to advocate for stronger conservation policies, limits on development, and stricter enforcement against the illegal pet trade. Public education campaigns, drawing on study findings, raise awareness about the turtles’ plight and encourage responsible actions, such as avoiding removing turtles from the wild or reporting illegal activities.

The box turtle, a creature of patience and profound resilience, embodies the very spirit of Turtle Island. Its survival is intertwined with the health of the forests, meadows, and wetlands that define this continent. Through dedicated, long-term population studies, illuminated by both scientific discovery and ancestral wisdom, humanity is offered a chance to understand, protect, and ultimately ensure that these living symbols of ancient Earth continue their slow, deliberate journey for generations to come. The future of the box turtle on Turtle Island depends on our collective commitment to listening, learning, and acting with the same steadfastness that these remarkable reptiles demonstrate every day.