The Burden of Peace: Black Kettle and the Cheyenne’s Tragic Pursuit of Survival

In the annals of American history, few figures embody the tragic paradox of peace amidst war as profoundly as Black Kettle, a principal chief of the Southern Cheyenne. His life, inextricably linked to the relentless westward expansion of the United States, became a testament to a leader’s unwavering commitment to harmony in the face of escalating conflict, broken promises, and ultimately, unimaginable violence. His story, and that of his people, is a searing indictment of Manifest Destiny’s brutal cost, a narrative etched in the blood-soaked sands of two infamous massacres.

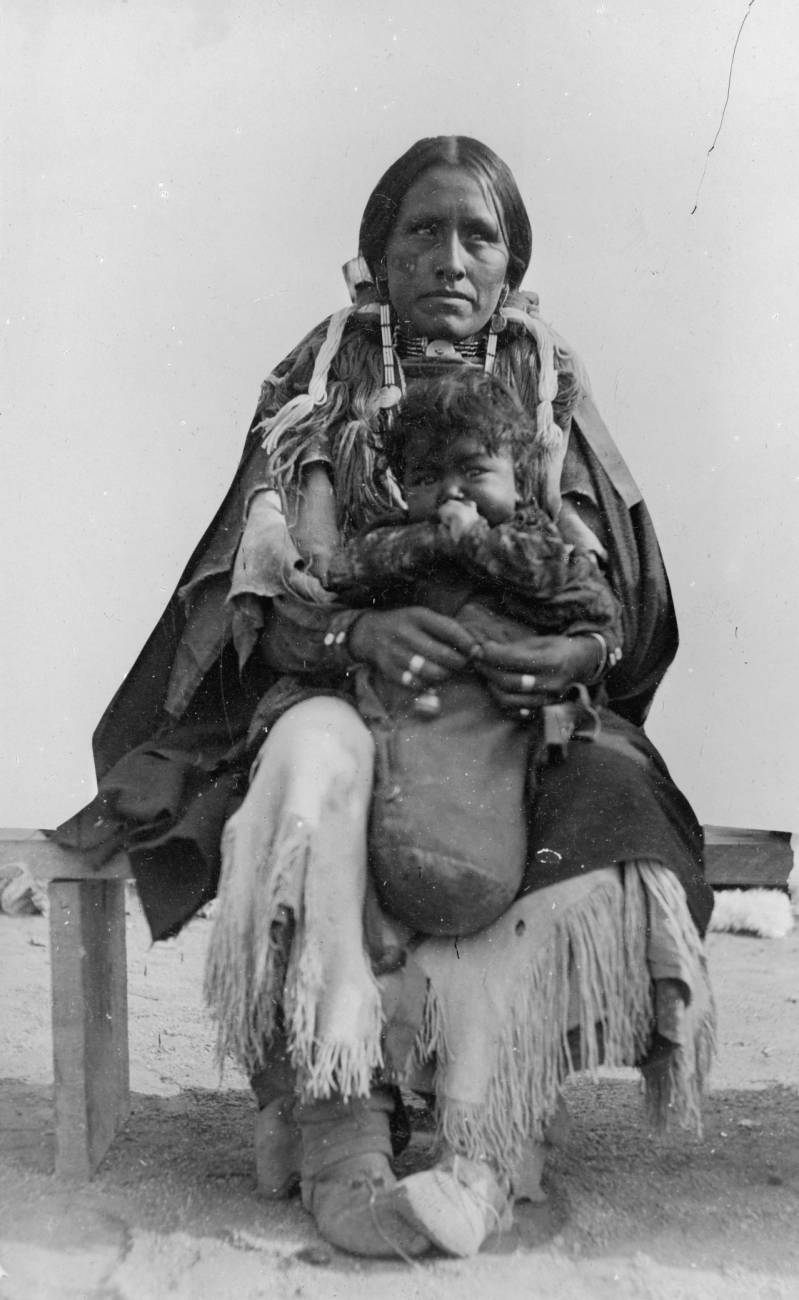

The Cheyenne, a people of the Great Plains, had for centuries thrived in a vast territory stretching from the Black Hills south into Colorado and Kansas. Their culture was rich, complex, and deeply spiritual, built around buffalo hunting, a sophisticated social structure, and a profound connection to the land. Black Kettle (Moketavato in Cheyenne), born around 1803, rose to prominence not as a war chief, but as a peace chief, a leader whose counsel emphasized diplomacy, negotiation, and the avoidance of bloodshed. This disposition, however, would prove a cruel irony in the tumultuous decades of the mid-19th century.

The discovery of gold in California in 1849, and later the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush in Colorado in 1858, sent a flood of white settlers, miners, and fortune-seekers across the Great Plains. This human tide, often violent and heedless of existing treaties, shattered the traditional Cheyenne way of life. Hunting grounds were despoiled, buffalo herds decimated, and vital resources depleted. The U.S. government, under immense pressure from its citizenry, began to renegotiate – or rather, unilaterally impose – treaties that drastically reduced Native lands.

The Treaty of Fort Wise in 1861 stands as a stark example. Signed by a minority of Cheyenne chiefs, including Black Kettle, it ceded most of the Cheyenne-Arapaho ancestral lands in Colorado, confining them to a fraction of their former territory along Sand Creek. Many Cheyenne leaders, particularly the militant Dog Soldiers, never recognized its legitimacy, igniting internal divisions and fueling resentment. Black Kettle, ever the pragmatist, believed that signing, however unjust, was the only path to survival for his people. He clung to the hope that peaceful coexistence was still possible, even as the drumbeat of war grew louder.

As the Civil War raged, the plains became a secondary, but no less brutal, theater of conflict. Raids by frustrated and desperate Native warriors, often the younger, more militant Cheyenne and Arapaho who rejected the Fort Wise treaty, provoked a harsh response from white settlers and the territorial militia. Governor John Evans of Colorado issued a proclamation in 1864, effectively declaring war on "hostile" Indians and encouraging citizens to "kill and destroy" them. Yet, he also promised protection to those who reported to military posts and evinced peaceful intentions.

It was this promise that Black Kettle desperately sought to fulfill. In the autumn of 1864, with winter approaching and his people vulnerable, he led a large band of Cheyenne and Arapaho to Fort Lyon, Colorado, seeking protection and a lasting peace. Major Edward Wynkoop, the sympathetic commander of Fort Lyon, assured Black Kettle of his safety and instructed him to camp along Sand Creek, about 40 miles northeast of the fort, where he flew both an American flag and a white flag of truce over his lodge. Wynkoop then rode to Denver to report to Governor Evans and Colonel John Chivington, commander of the Colorado Volunteers, advocating for peace.

Chivington, a Methodist minister turned military officer, held a deeply hostile view of Native Americans. He famously declared, "Damn any man who is in sympathy with Indians!" and reportedly said that his orders were to "kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice." Ignoring Wynkoop’s pleas and the clear evidence of peaceful intent, Chivington led a force of some 700 men – a mix of regular cavalry and "100-day" Colorado Volunteers – on a forced march to Sand Creek.

At dawn on November 29, 1864, Chivington’s troops descended upon Black Kettle’s sleeping camp. The American flag and white flag flew, as instructed. Black Kettle, hearing the commotion, reportedly raised the American flag higher, shouting to his people that the soldiers were friends and would not harm them. His trust was tragically misplaced. The soldiers opened fire indiscriminately. Men, women, and children were slaughtered as they fled. Estimates vary, but between 150 and 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho were killed, mostly women, children, and the elderly. The brutality was horrific: bodies were mutilated, scalped, and dismembered. One witness described how "babies were scalped and their brains knocked out; the women cut open and their unborn children torn out."

The Sand Creek Massacre sent shockwaves through the nation. While initially hailed as a victory, later investigations by Congress and a military commission condemned Chivington’s actions as a "foul and dastardly massacre." The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War concluded that "the truth is that he surprised and murdered, in cold blood, the unsuspecting men, women, and children of this band of Indians." Chivington escaped court-martial, but his reputation was ruined.

Black Kettle, miraculously, survived the massacre, though his wife was shot multiple times and many of his family members were killed. Despite the unspeakable horror he had endured, his commitment to peace remained unbroken. He understood that further war would only lead to the annihilation of his people. "We are here by the will of the Great Father of War, and I hope that ere long we shall have peace," he told a U.S. commissioner a year after Sand Creek. "We have been living in peace and we are anxious to live in peace."

His efforts led to the Treaty of the Little Arkansas in 1865, which offered some compensation to the Sand Creek survivors and promised new lands. Yet, even this treaty was quickly undermined by the relentless expansion and the continued violence of the Plains Wars. The more militant Dog Soldiers, now even more embittered by Sand Creek, continued their resistance, often clashing with U.S. troops and settlers, creating a dangerous cycle of retaliation that Black Kettle desperately tried to break.

By 1867, Black Kettle was a signatory to the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, which aimed to permanently relocate the Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache to reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Black Kettle, always seeking a path to survival, agreed, hoping this final move would bring the peace his people so desperately craved. He led his band to their new reservation, seeking to adapt to the imposed changes and live in accordance with the treaty.

However, the U.S. Army, under the command of General Philip Sheridan, launched a winter campaign in 1868 against "hostile" Indians who were still off-reservation or engaging in raids. Sheridan’s strategy was to strike at winter camps, where families were most vulnerable. Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, leading the 7th U.S. Cavalry, was tasked with finding and punishing these bands.

On November 27, 1868, exactly four years to the day after Sand Creek, Custer’s troops located a large Cheyenne camp along the Washita River in Indian Territory. This was Black Kettle’s village, which, according to treaty terms, was supposed to be under military protection. Once again, Black Kettle had an American flag flying over his lodge, a sign of his peaceful intentions and compliance.

Custer’s 7th Cavalry attacked at dawn. The surprise was complete. Black Kettle, hearing the gunfire, reportedly mounted his horse with his wife. Both were shot down in the river, their bodies found later among the dead. The attack, often framed as a battle by Custer and his supporters, was in reality another massacre. While some warriors fought back, many of the casualties were women and children. Custer’s men destroyed the village, killed the pony herd, and took women and children captive.

The Washita Massacre cemented Black Kettle’s tragic legacy. He was a man who, against overwhelming odds and profound personal loss, clung to the belief that peace was attainable. He consistently sought diplomatic solutions, even when betrayed, only to be met with the unyielding force of a nation determined to expand at any cost. His life illustrates the futility of peaceful resistance when confronted with genocidal intent and systemic broken promises.

Black Kettle’s story is not merely one of victimization; it is also one of profound resilience and moral courage. He chose a path of peace not out of weakness, but out of a deep understanding of his people’s needs and a strategic foresight that further war would only hasten their demise. His efforts, though ultimately unsuccessful in averting tragedy for himself, allowed many of his people to survive and eventually rebuild.

Today, Black Kettle remains a potent symbol. For the Cheyenne people, he is a revered ancestor, a leader who tirelessly worked for their well-being. For the broader American consciousness, his story serves as a stark reminder of the dark chapters of the nation’s past, urging a deeper examination of the narratives of conquest and the profound human cost of westward expansion. His flags, flying bravely in the face of overwhelming aggression, continue to wave as a silent, enduring testament to the burden of peace in a time of war. The tragic echoes of Sand Creek and Washita remind us that true peace requires not just good intentions, but justice, respect, and the honoring of sacred trust.