The Echoes of Washita: A Legacy Forged in Blood and Contradiction

The crisp dawn air of November 27, 1868, shattered over the Washita River in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) as Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, astride his horse, led the U.S. 7th Cavalry in a thunderous charge. What transpired that day, ostensibly a decisive victory for the U.S. Army in the ongoing Indian Wars, remains one of the most hotly contested and morally complex chapters in American history. Was it a legitimate battle against hostile warriors, or a brutal massacre of a peaceful village? The Battle of Washita, as it is officially known, is a crucible where military strategy, political ambition, and the tragic clash of cultures were forged into a legacy that continues to resonate, challenging simplistic narratives and demanding a deeper, more nuanced historical analysis.

To understand Washita, one must first grasp the tumultuous backdrop of the American West in the late 1860s. The relentless westward expansion of settlers, fueled by the promise of land and resources, collided head-on with the indigenous peoples who had inhabited these lands for millennia. Treaties were signed, then often broken, leading to a cycle of resentment, retaliatory raids, and military campaigns. The Southern Plains tribes – primarily the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa – found their traditional hunting grounds shrinking, their way of life threatened, and their very survival at stake.

The U.S. government’s policy, largely driven by figures like General William Tecumseh Sherman and General Philip Sheridan, was one of subjugation. Sheridan famously declared, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," encapsulating a brutal strategy aimed at breaking the tribes’ will to resist. The winter months, when tribes were settled in their camps, horses were weak, and food supplies dwindled, were seen as the opportune time to strike. This strategic imperative would directly lead to Washita.

At the heart of the Washita story lies Chief Black Kettle, a leader of the Southern Cheyenne. Black Kettle was a man who had repeatedly sought peace, even after enduring unimaginable horror. Just four years prior, in November 1864, his peaceful Cheyenne village at Sand Creek, Colorado, was attacked by Colonel John Chivington’s Colorado Volunteers. Despite flying American flags and white surrender banners, hundreds of Cheyenne, mostly women, children, and elderly men, were slaughtered in what became known as the Sand Creek Massacre. Black Kettle survived, a testament to his resilience, but forever marked by the atrocity. He continued to advocate for peace, moving his band to what he believed was a designated safe area along the Washita River, under the terms of the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek (1867). He was under the impression that his camp was not considered hostile, even if some younger, more aggressive warriors from other bands had used the area.

However, the U.S. Army, under Sheridan’s command, viewed all un-surrendered camps as legitimate targets, especially after a series of raids by various tribes along the Kansas frontier in the summer and fall of 1868. Sheridan tasked Custer and the 7th Cavalry with a winter campaign to "punish" these tribes and force them onto reservations. Custer, a flamboyant and ambitious officer eager to restore a reputation tarnished by a recent court-martial, embraced the mission with characteristic zeal.

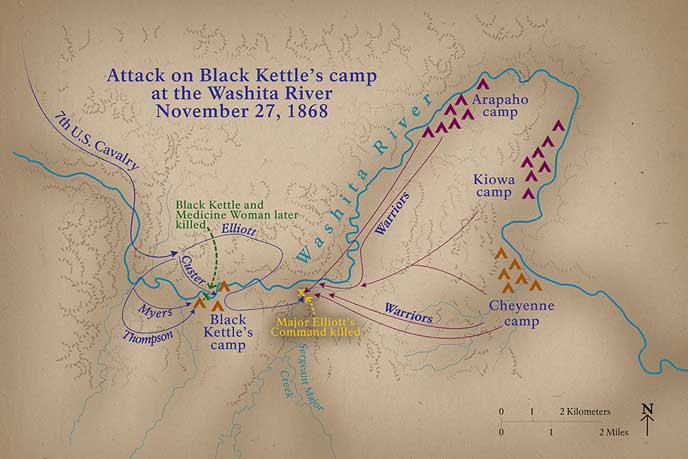

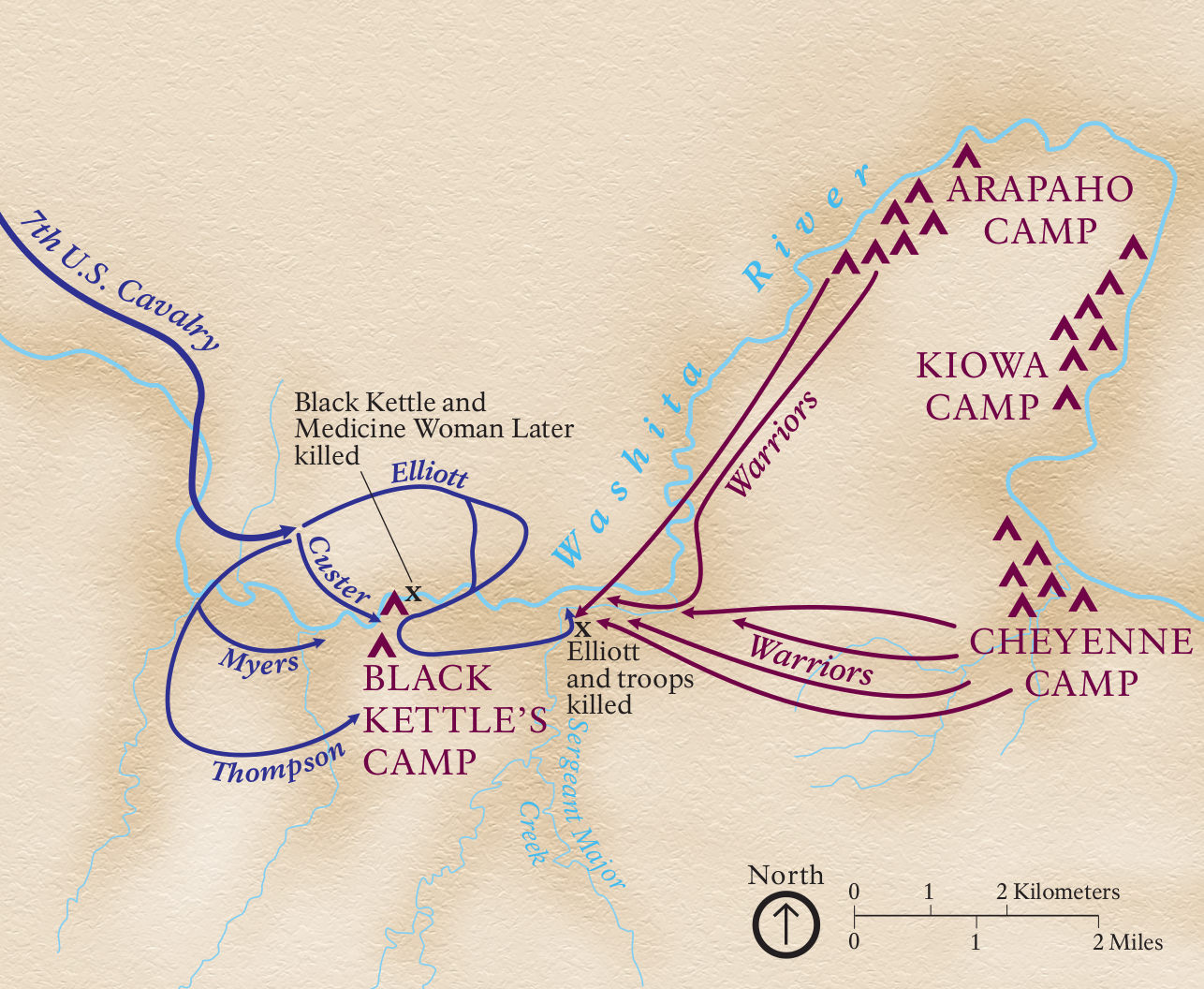

On November 26, after a grueling march through a blizzard, Custer’s scouts located a large Indian village along the Washita River. Unbeknownst to Custer, this was Black Kettle’s village, nestled amongst a series of other camps belonging to various Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa bands stretching for miles downriver. Custer, believing he had found a major hostile encampment, ordered an immediate attack at dawn.

The attack itself was a textbook example of a surprise cavalry assault. Under the cover of darkness, the 7th Cavalry divided into four battalions, encircling the sleeping village. As the first light touched the horizon, the bugles blared "Garryowen," the 7th Cavalry’s regimental tune, and the troopers charged. The chaos that ensued was absolute. Men, women, and children, roused from sleep, were caught in a hail of gunfire. Black Kettle and his wife, attempting to flee on horseback, were shot down in the river.

Custer’s official report hailed the engagement as a resounding success, a "glorious victory." He claimed that 103 warriors were killed, along with the destruction of the village and its winter supplies. The 7th Cavalry suffered minimal casualties, losing only Major Joel Elliott and 19 men who had pursued fleeing Cheyenne downriver and were subsequently cut off and killed by warriors from the downstream camps. To prevent the remaining horses from falling into enemy hands, Custer ordered the slaughter of over 800 ponies, a devastating blow to the nomadic Cheyenne way of life.

However, the celebratory narrative quickly began to fray. Critics, even within Custer’s own command, questioned the nature of the "battle." Captain Frederick Benteen, a veteran officer who would later be at Little Bighorn, was openly critical, suggesting that many of the "warriors" killed were in fact women and children. Cheyenne survivors recounted horrific tales of non-combatants being shot down without mercy. Moving statistics and quotes provide chilling insights:

- Cheyenne perspective: "Soldiers shot us as we ran, not caring if we were men, women, or children," recalled one survivor, a child at the time. Another, Chief Lone Wolf of the Kiowa, observing the aftermath from a distance, remarked, "This was not a fight, it was a massacre of sleeping people."

- Military dissent: Major Elliott’s disappearance and the subsequent failure of Custer to mount a thorough search for him fueled resentment. Benteen famously wrote a letter critical of Custer’s actions, stating, "Custer could have found Elliott if he had wanted to." This internal criticism highlighted concerns about Custer’s priorities and his potential disregard for his men.

- Archaeological evidence: Modern archaeological digs at the Washita battlefield site have unearthed evidence supporting the presence of non-combatant casualties, including children’s toys and women’s adornments amidst spent cartridges and other battle debris.

The historical analysis of Washita hinges on the deeply intertwined questions of intent and context. From a purely military perspective, Custer achieved a decisive tactical victory. He surprised an enemy camp, inflicted heavy casualties, destroyed essential supplies, and disrupted their ability to wage war during the critical winter months. This aligned perfectly with Sheridan’s "total war" strategy aimed at breaking the Plains tribes.

Yet, from the perspective of the Cheyenne and many modern historians, Washita was a massacre. Black Kettle’s village, while perhaps containing some warriors who had participated in recent raids, was fundamentally a peace camp. Black Kettle himself had a proven track record of seeking accommodation, and many of the inhabitants were non-combatants. The indiscriminate nature of the attack, particularly the high number of women and children among the dead, points to an operation that went beyond a conventional military engagement. The precedent of Sand Creek looms large, suggesting a pattern of U.S. military attacks on vulnerable, peaceful or semi-peaceful Native American communities.

The legacy of Washita profoundly shaped Custer’s career and his ultimate fate. It solidified his reputation as an aggressive, daring "Indian fighter," earning him accolades in the press and from his superiors. However, it also sowed seeds of distrust and resentment among some of his own officers and, more significantly, cemented the Cheyenne’s resolve to resist the U.S. Army. The memory of Washita, and Sand Creek before it, fueled the fierce determination of warriors who would face Custer again, eight years later, at the Little Bighorn. Many of the Cheyenne and Arapaho who fought Custer to his death in 1876 had either been present at Washita or had family members who died there. The thirst for revenge, for justice, was a palpable force.

Today, the Washita Battlefield National Historic Site stands as a solemn reminder of this contested history. It is a place dedicated to presenting multiple perspectives, acknowledging the tragedy for the Cheyenne people, and analyzing the military context for the U.S. Army. The site encourages visitors to grapple with the complexities, to understand that history is rarely black and white, and that the narratives of victors often obscure the suffering of the vanquished.

The Battle of Washita is not merely a footnote in the annals of the Indian Wars; it is a profound historical mirror. It reflects the brutal realities of westward expansion, the devastating consequences of cultural collision, and the enduring challenge of reconciling conflicting historical truths. It forces us to confront difficult questions about heroism and atrocity, about military necessity and moral responsibility. The echoes of that cold November dawn along the Washita River continue to resonate, urging us to listen to all voices and to learn from a past that remains, in many ways, an open wound on the American conscience.