Echoes of a Vanished Land: The Tragic Saga of Idaho’s Bannock War

In the scorching summer of 1878, the rolling plains and rugged mountains of southern Idaho became the crucible of a desperate and brutal conflict – the Bannock War. Far from the grand narratives of the Civil War or the dramatic campaigns on the Great Plains, this lesser-known chapter of American history embodies the tragic collision of cultures, broken promises, and the desperate fight for survival that defined the westward expansion. It was a war born of starvation, fueled by injustice, and ultimately, a poignant testament to the vanishing way of life for Idaho’s Indigenous peoples.

The story of the Bannock War is inextricably linked to the land itself, particularly the vast, fertile Camas Prairie. For millennia, the Bannock and their Shoshone kin had thrived in this region, their lives intricately woven into the rhythms of the seasons. Expert horsemen and skilled hunters, they followed the buffalo herds, harvested salmon from the rivers, and, crucially, gathered the nutrient-rich bulbs of the camas plant (Camassia quamash). The camas, a starchy, onion-like root, was not merely a food source; it was a dietary staple, a trade commodity, and a spiritual anchor, central to their cultural identity and survival. The Camas Prairie, a verdant expanse blooming purple with the plant’s flowers in spring, was their ancestral grocery store, pharmacy, and sacred ground.

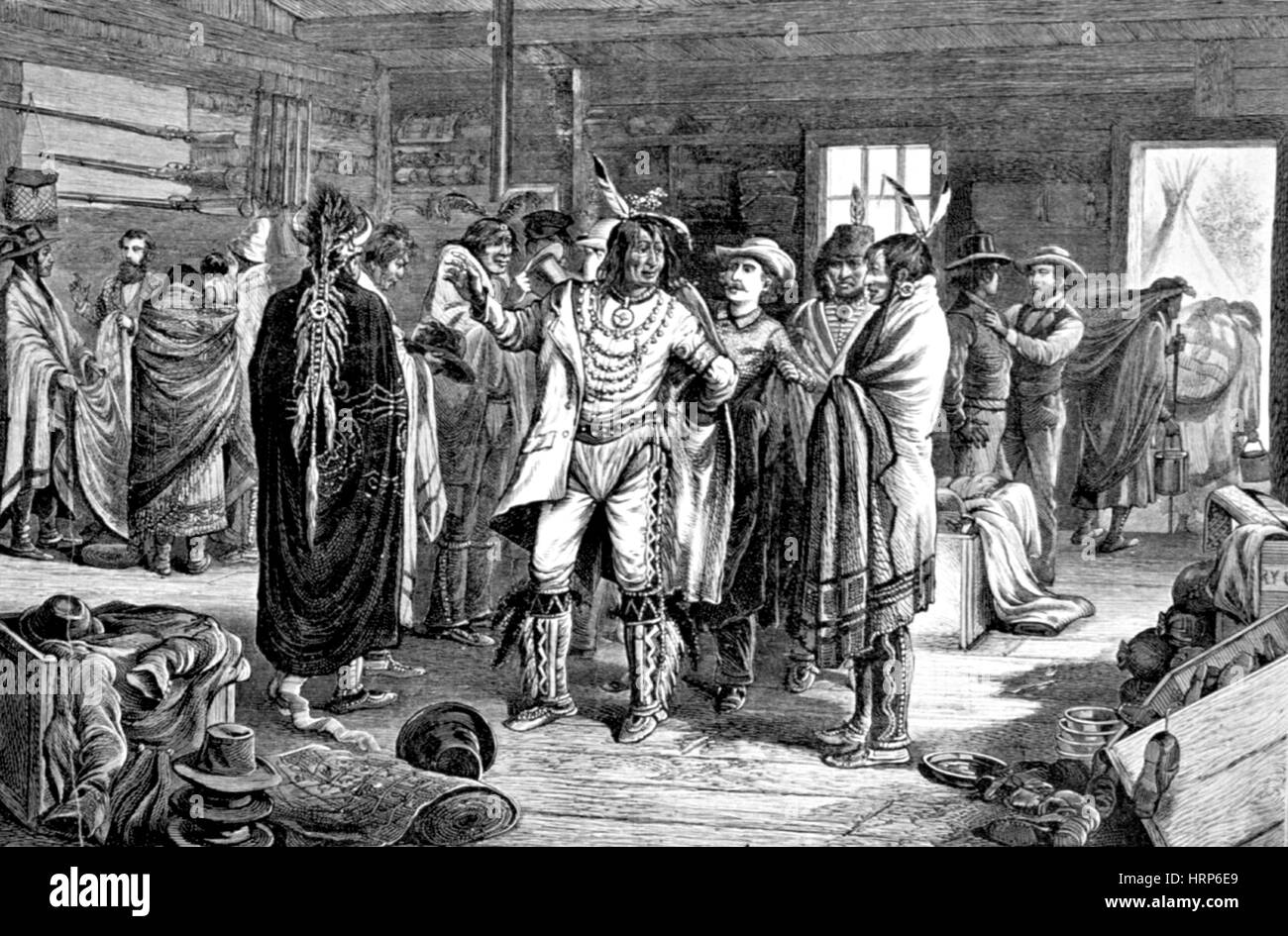

The arrival of Euro-American settlers in the mid-19th century shattered this ancient harmony. The lure of gold, fertile land for farming, and the promise of a new life drew a relentless tide of pioneers into the Idaho Territory. Treaties, often signed under duress and rarely honored, became the primary tool for dispossessing Indigenous nations of their lands. The Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868, for instance, established the Fort Hall Reservation for the Shoshone and Bannock, promising annuities, farming implements, and most importantly, guaranteed hunting rights on "unoccupied lands" and continued access to traditional gathering grounds, including the Camas Prairie.

However, the ink on the treaty was barely dry before its provisions began to unravel. Settlers, undeterred by treaty lines, encroached further onto traditional Bannock lands. Miners scarred the landscape, farmers plowed under hunting grounds, and, most devastatingly, thousands of settler hogs were turned loose on the Camas Prairie. These ravenous animals, rooting voraciously, systematically destroyed the very camas bulbs that were the lifeblood of the Bannock people. "The white man’s hogs," as one historian noted, "were as effective as any army in destroying the Bannock way of life." The pigs didn’t just eat the camas; they churned the soil, making it impossible for future harvests.

By the spring of 1878, starvation was a tangible, agonizing reality on the Fort Hall Reservation. Annuities were late or insufficient, government agents were often corrupt or indifferent, and the promise of self-sufficiency through farming had largely failed due to unsuitable land and lack of resources. The Bannock, led by chiefs like Buffalo Horn, watched their children sicken and their elders weaken, their traditional food source obliterated.

The spark that ignited the war was a confrontation on the Camas Prairie in May 1878. A group of Bannock women and children, desperate for food, were attempting to gather the few remaining camas bulbs when they were confronted by white settlers. An argument escalated into violence, resulting in the killing of several settlers. For the Bannock, this was not an act of aggression but a desperate defense of their fundamental right to survive. For the settlers and the U.S. Army, it was an "outbreak" that demanded swift and decisive retribution.

Chief Buffalo Horn, a charismatic and respected leader, made a fateful decision: to fight rather than starve. He rallied his people, and soon, other desperate bands of Northern Paiutes, many of whom had suffered similar injustices and faced their own impending starvation on the Malheur Reservation in Oregon, joined the Bannock. These Paiutes, under the leadership of chiefs like Egan, had seen their reservation land opened to white settlement, their promised supplies vanish, and their people treated with disdain. The Malheur Reservation, once a sanctuary, had become a prison of poverty. The alliance, however, was tenuous, born of shared desperation rather than a unified strategic vision.

The U.S. Army, still reeling from the Nez Perce War of the previous year, mobilized quickly. General Oliver O. Howard, who had pursued Chief Joseph across Idaho and Montana, was once again tasked with quelling an "Indian uprising." Howard, a seasoned veteran of the Civil War, commanded a substantial force, including infantry, cavalry, and a contingent of Umatilla scouts, themselves Indigenous people often caught between worlds.

The war unfolded across a vast, unforgiving landscape. The Native forces, though numbering perhaps 500-700 warriors and many more women and children, were lightly armed, primarily with bows and arrows and a few aging firearms. They employed guerrilla tactics, launching swift raids on isolated ranches and settlements, seizing supplies, and striking fear into the hearts of settlers. Their objective was not conquest, but survival and, perhaps, a return to their traditional lands.

One of the most significant engagements occurred at Silver Creek, near present-day Oregon, on July 8, 1878. General Howard’s forces, under the command of Captain Reuben F. Bernard, engaged a large body of Bannock and Paiute warriors. The battle was fierce, characterized by entrenched positions and determined fighting from both sides. While the Army sustained casualties, the Native forces suffered heavy losses, including many of their horses, which were vital for their mobility and hunting. The Battle of Silver Creek, though not a decisive victory for the Army, severely crippled the Native ability to wage war effectively.

As the summer wore on, the Native resistance began to fracture. The alliance with the Paiutes, already strained by differing goals and dwindling resources, started to crumble. Chief Egan, a prominent Paiute leader, was tragically killed in late July by Umatilla scouts who were pursuing him. His death, a result of betrayal rather than direct combat, demoralized many Paiutes, leading to their surrender or dispersal. The "interesting fact" here is the brutal efficiency of the Army’s strategy of utilizing Indigenous scouts who often had long-standing rivalries with the warring tribes, or who were offered bounties, further fragmenting Native resistance.

The Bannock, under Buffalo Horn, continued their desperate flight, moving eastward, hoping to reach the buffalo grounds of Wyoming or find refuge with other tribes. But the relentless pursuit by the Army, combined with starvation, disease, and a lack of ammunition, took an unbearable toll. Small bands began to surrender, while others, like Buffalo Horn’s group, fought until they could fight no more. Buffalo Horn himself was eventually killed in a skirmish in Wyoming in August 1878.

By the fall of 1878, the Bannock War was effectively over. Hundreds of Native people had been killed, many more captured. The surviving Bannock and Paiutes faced a grim future. Most were forced back onto reservations, primarily Fort Hall, where conditions remained dire. The Malheur Reservation was subsequently dissolved, its remaining Paiute inhabitants dispersed, some sent to the Yakama Reservation in Washington, others to Fort Hall, severing them from their ancestral lands and cultural ties.

The legacy of the Bannock War is a stark reminder of the costs of westward expansion. It highlights the systemic failure of treaty obligations, the devastating impact of cultural destruction, and the sheer desperation that drove Indigenous peoples to take up arms against overwhelming odds. For the white settlers, it was a necessary "Indian War" that secured their dominance over the land. For the Bannock and Shoshone, it was a profound tragedy, a desperate fight for their very existence, and a testament to the enduring connection between a people and their land.

Today, the Camas Prairie still blooms each spring, a vibrant purple carpet that silently testifies to a forgotten history. The descendants of the Bannock and Shoshone at Fort Hall continue to fight for their rights, preserve their culture, and remember the sacrifices made in the summer of 1878. The Bannock War, though often overshadowed by other conflicts, remains a vital, painful chapter in Idaho’s history, a somber echo of a vanished way of life, and a powerful call for understanding and remembrance.