Bridging Worlds: Augmented Reality’s Promise for Turtle Island Education

Across the vast and diverse landscapes of Turtle Island – the Indigenous name for North America – a quiet revolution is stirring in education. Far from the traditional classroom, a new technology, Augmented Reality (AR), is emerging as a powerful tool to revitalize languages, preserve histories, and transmit cultural knowledge for future generations. Imagine students not just reading about their ancestors, but virtually walking through ancient villages, hearing stories in their ancestral tongue, or seeing traditional practices unfold before their eyes, all within their own community. This is the transformative potential of AR for Indigenous education.

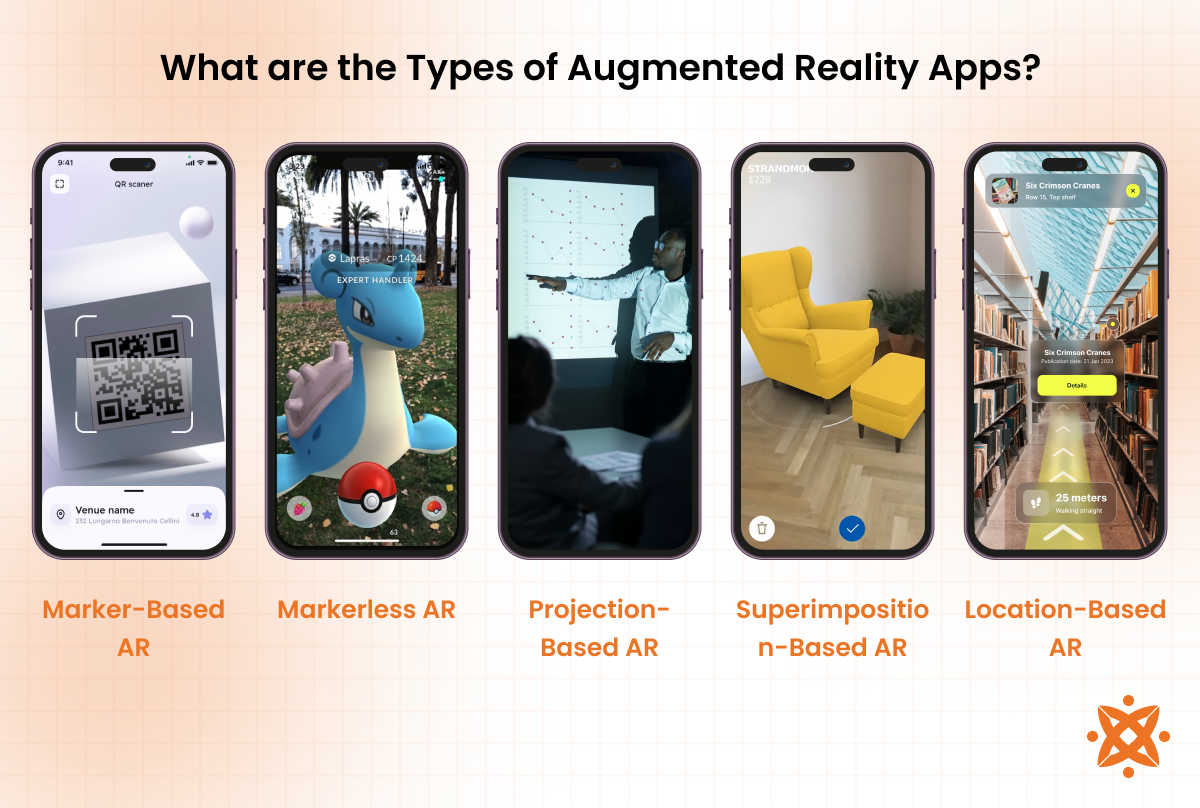

Augmented Reality, distinct from Virtual Reality, overlays digital information onto the real world, enhancing our perception rather than replacing it. Through a smartphone, tablet, or specialized AR glasses, learners can experience 3D models, interactive animations, audio narratives, and textual information anchored to physical locations or objects. For education, AR’s power lies in its ability to make abstract concepts tangible, historical events immediate, and distant cultures accessible, fostering a level of engagement and immersion traditional methods often struggle to achieve.

For Indigenous communities on Turtle Island, the need for innovative educational tools is particularly acute. Centuries of colonial policies, residential schools, and systemic suppression have severely impacted Indigenous languages, cultural practices, and the intergenerational transmission of knowledge. Many Indigenous languages are critically endangered; UNESCO estimates that over half of the world’s spoken languages are at risk of disappearing, with Indigenous languages disproportionately represented. Moreover, mainstream curricula often perpetuate historical inaccuracies or omit Indigenous perspectives entirely, contributing to a sense of alienation among Indigenous youth and a lack of understanding among non-Indigenous learners. AR offers a unique pathway to reclaim, revitalize, and share authentic Indigenous knowledge.

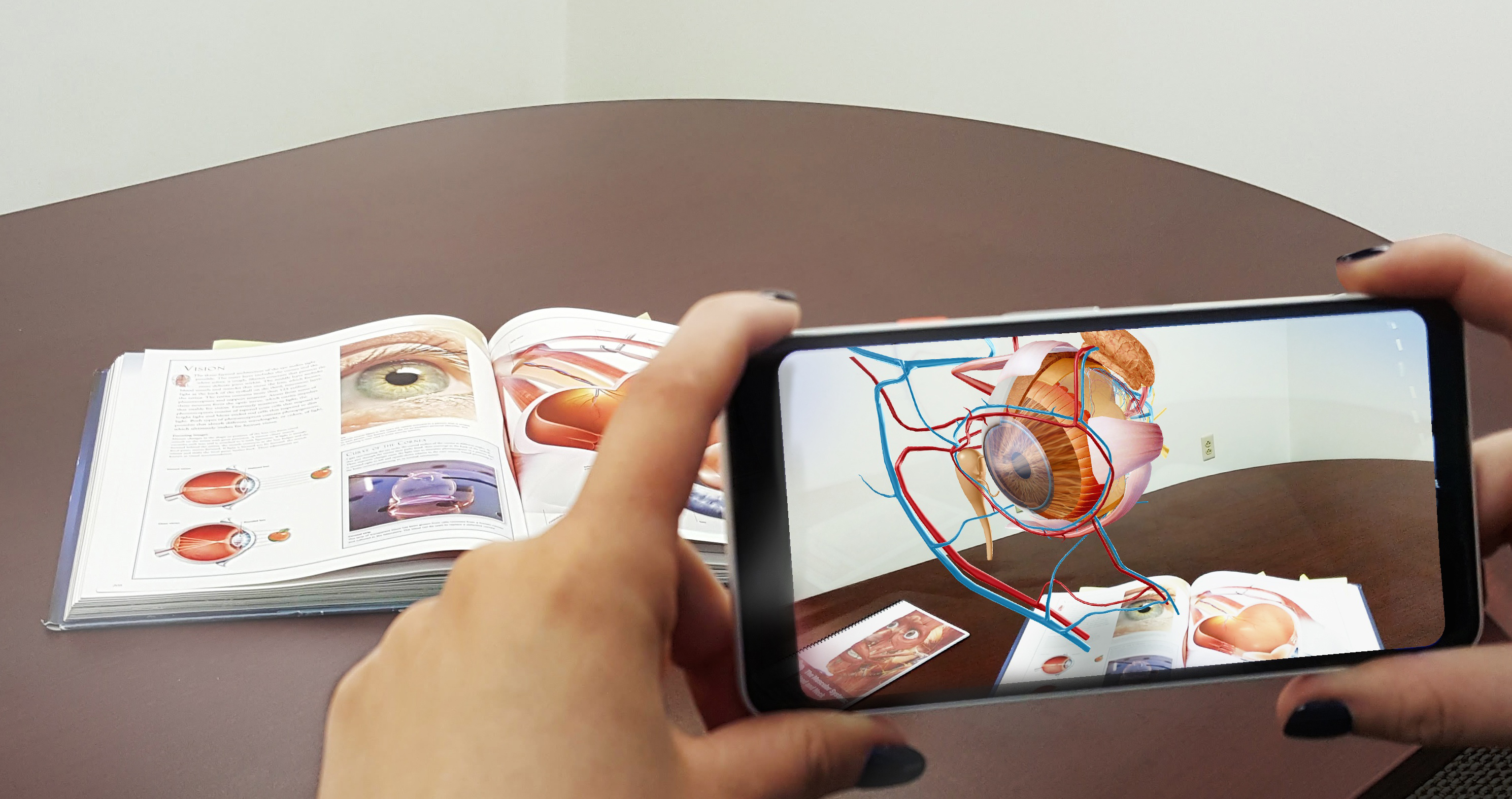

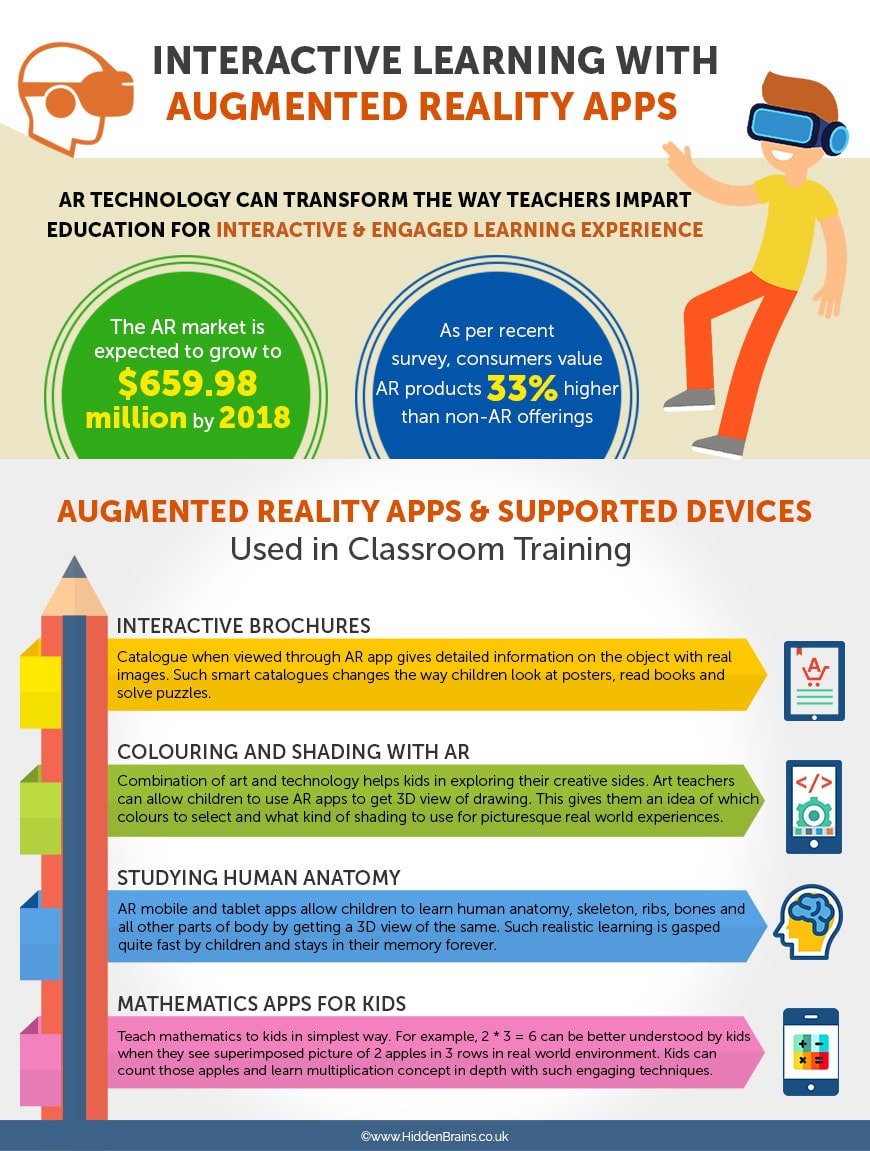

One of the most profound applications of AR in this context is language revitalization. Imagine an AR app that allows a student to point their device at a plant, an animal, or a household object, and immediately see its name appear in their ancestral language – Cree, Ojibwe, Mohawk, Navajo, or any of the hundreds of Indigenous languages across Turtle Island. The app could then play an audio recording of a fluent Elder pronouncing the word, perhaps even incorporating a short story or cultural context associated with the object. This interactive, real-world application moves beyond flashcards, grounding language learning in the immediate environment and cultural relevance. "Language is the heart of our culture," says Dr. Jessie Young, a Mohawk language educator. "AR provides a dynamic way to bring our words back into daily life, making them visible and audible in our homes and on our lands."

Beyond language, AR can breathe life into history and cultural preservation. Students visiting an ancestral site could use an AR app to overlay virtual representations of what the area looked like centuries ago – a bustling village, a traditional longhouse, or a ceremonial ground. They could interact with virtual historical figures, listen to oral histories, or witness traditional ceremonies, gaining a deeper, embodied understanding of their heritage. For museums and cultural centres, AR can transform static displays into interactive portals, allowing visitors to see how an artifact was used, hear the stories behind it in an Indigenous voice, or even view its 3D model from all angles, providing context that a simple plaque cannot convey. This ensures that the narrative remains in the hands of the knowledge keepers, rather than being interpreted solely by external institutions.

Land-based learning, a cornerstone of many Indigenous pedagogies, is another area where AR shines. Indigenous knowledge systems are deeply intertwined with the land, understanding its ecology, history, and spiritual significance. An AR app could allow users to explore their traditional territories, overlaying historical migration routes, the locations of significant cultural events, or information about traditional plant medicines and their uses. Students could learn about sustainable land management practices passed down through generations, visualizing the impact of different approaches on the environment in real-time simulations. This fosters a profound connection to the land, reinforcing stewardship and traditional ecological knowledge. "Our land is our first teacher," states Elder William Many Horses. "AR can help our youth see the layers of history and knowledge embedded in every rock and tree."

The benefits extend beyond individual learning. AR apps, developed in collaboration with and led by Indigenous communities, can serve as powerful tools for intergenerational knowledge transfer. Elders can share their wisdom in a format that resonates with digitally-native youth, creating new avenues for storytelling and cultural transmission. These applications can also foster pride and identity among Indigenous youth, countering negative stereotypes and empowering them with a deeper connection to their heritage. For non-Indigenous learners, these AR experiences offer authentic, immersive encounters with Indigenous cultures, fostering empathy, understanding, and reconciliation – essential steps towards building more equitable societies.

However, the path to integrating AR into Indigenous education is not without its challenges. The digital divide remains a significant barrier, with many remote Indigenous communities lacking reliable high-speed internet access or access to necessary devices. The cost of developing high-quality AR content and applications can also be substantial, requiring significant investment and technical expertise. Crucially, the development process must be community-led, ensuring that content is culturally appropriate, accurate, and reflects the specific knowledge and values of the respective nations. Without this Indigenous ownership and oversight, there is a risk of perpetuating colonial practices through new technological means, such as cultural appropriation or misrepresentation. Data sovereignty – the right of Indigenous nations to govern their own data – must be a foundational principle in any AR initiative.

Despite these hurdles, the momentum is building. Initiatives like the "Sámi Language and Culture VR/AR" project in Norway and similar burgeoning projects in Canada and the US demonstrate the viability and impact of this technology when approached respectfully and collaboratively. The future envisions not just individual apps, but comprehensive AR ecosystems that integrate language learning, historical narratives, environmental education, and cultural arts, all accessible on Turtle Island’s varied terrains.

Ultimately, Augmented Reality offers more than just a technological gimmick; it represents a powerful instrument for decolonization and revitalization. By empowering Indigenous communities to curate, create, and share their own narratives, languages, and knowledge systems in innovative, engaging ways, AR can help mend the broken threads of history. It can serve as a bridge, connecting past traditions with future generations, ensuring that the vibrant, diverse cultures of Turtle Island continue to thrive, resonate, and educate the world for centuries to come. The promise of AR is not just to see the world differently, but to see our place within it, enriched by the wisdom of those who have called this land home since time immemorial.