Untamed Spirit: The Apache Leaders’ Fierce Resistance Against U.S. Military Expansion

In the rugged, sun-baked landscapes of what is now the American Southwest, a profound and tragic clash of civilizations unfolded in the 19th century. On one side stood the burgeoning might of the United States, fueled by Manifest Destiny and an insatiable hunger for land and resources. On the other, a constellation of Apache bands, whose very existence was inextricably linked to these harsh yet bountiful territories. Their resistance, characterized by an indomitable spirit, strategic brilliance, and an unwavering commitment to their ancestral lands, stands as one of the most compelling and heartbreaking chapters in American history. It was a struggle for survival against overwhelming odds, a testament to the human will to remain free.

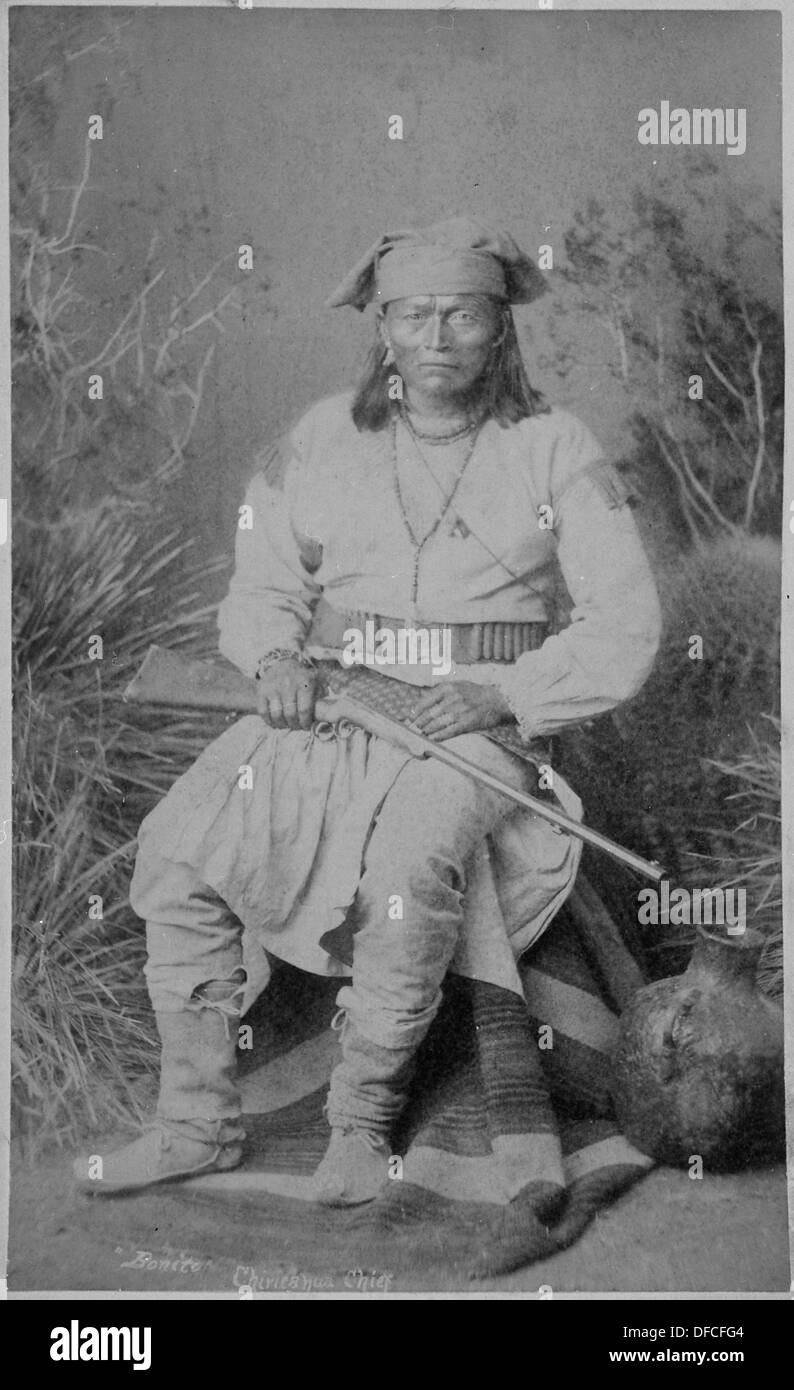

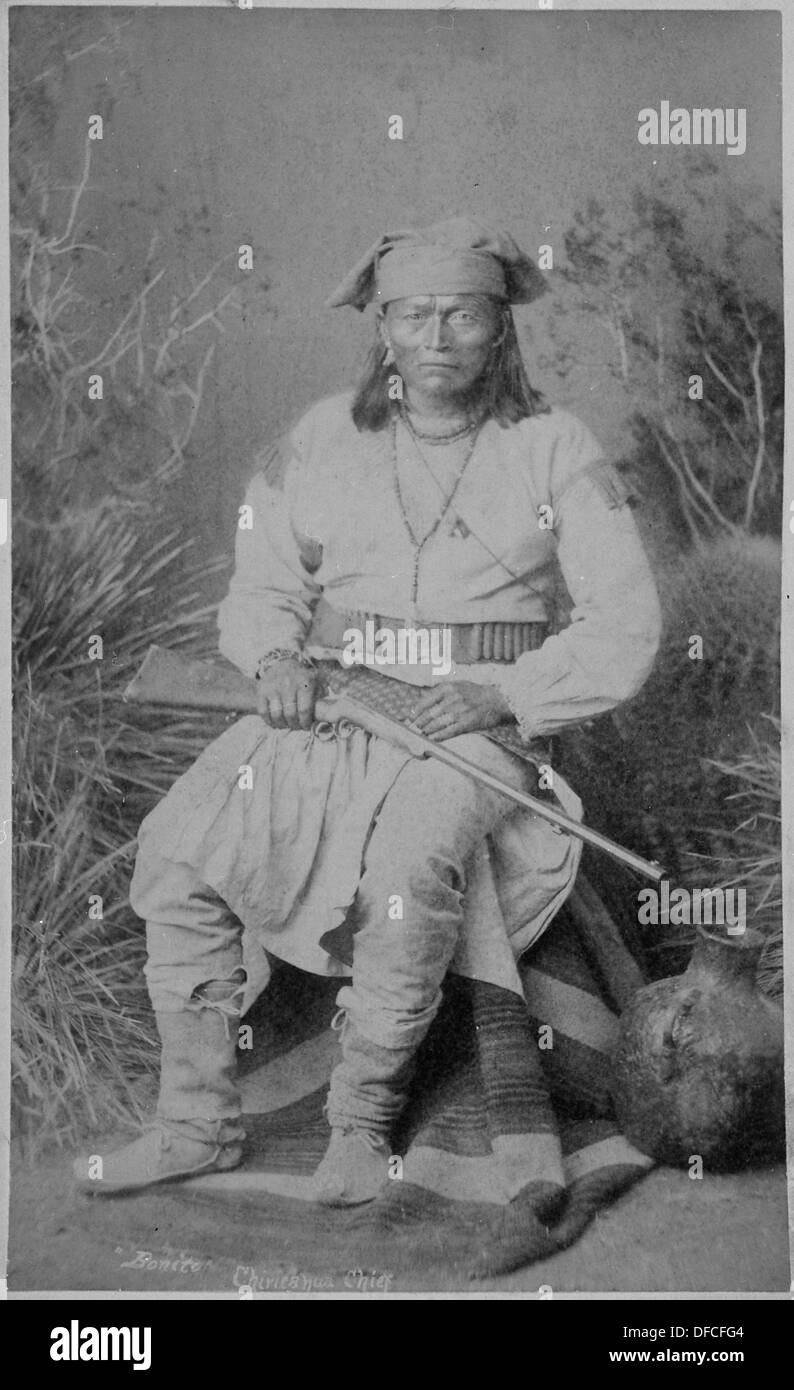

The Apache people, a collection of culturally related but distinct groups including the Chiricahua, Mescalero, Mimbreño, and Western Apache, had for centuries thrived in the arid expanses of Arizona, New Mexico, and northern Mexico. They were master horsemen, fierce warriors, and ingenious survivalists, intimately familiar with every canyon, waterhole, and mountain pass. Their decentralized social structure, based on family groups and band leaders, made them resilient but also challenging to unify against a common enemy. For generations, they had defended their territories against Spanish, and later Mexican, incursions, developing a formidable reputation that preceded the arrival of American settlers.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, which ended the Mexican-American War, ceded vast territories to the United States, including Apache lands. This geopolitical shift marked the beginning of the end for the Apache way of life. The discovery of gold, the subsequent influx of miners and settlers, and the U.S. government’s policy of westward expansion rapidly intensified the pressure on Apache territories. Suddenly, their traditional hunting grounds became contested land, their raiding economy – a long-standing practice against rival tribes and, historically, Mexican settlements – was deemed banditry, and their very presence an impediment to "progress."

One of the earliest and most influential figures in this period of escalating conflict was Mangas Coloradas (Red Sleeves), a towering Mimbreño Apache chief. A brilliant strategist and diplomat, Mangas Coloradas initially sought peaceful coexistence with the Americans, even signing a treaty in 1852. However, a series of betrayals and atrocities committed by American settlers, notably the brutal lashing he received in 1851 at a mining camp near Pinos Altos, solidified his resolve for resistance. He forged alliances with other Apache leaders, including the young Cochise, creating a formidable force against the encroaching tide. Mangas Coloradas understood the existential threat posed by the Americans. His leadership during the 1850s saw a coordinated effort to resist American incursions, demonstrating an early strategic vision that defied the image of scattered, unorganized tribes.

The betrayal and murder of Mangas Coloradas in 1863, under a flag of truce, by U.S. soldiers, sent shockwaves through the Apache nation. It extinguished any remaining hope for a peaceful resolution for many and fueled a deep-seated mistrust that would last for decades. His death, a stark example of American duplicity, hardened the hearts of those who followed him, transforming localized grievances into a widespread and desperate struggle for survival.

Cochise, the formidable chief of the Chokonen Chiricahua Apache, emerged as another iconic leader of the resistance. His initial relationship with Americans was, by some accounts, cordial. However, the infamous "Bascom Affair" of 1861 irrevocably altered his path. Falsely accused of kidnapping a settler’s child, Cochise and his family were lured into a parley by Lieutenant George Bascom, only to be ambushed. Though Cochise escaped, his relatives were held hostage, and when Bascom executed them, Cochise retaliated by killing his own American hostages. This incident ignited a decade-long war across Arizona and New Mexico, a conflict that turned one of the most powerful Apache leaders into an implacable foe.

Cochise, a military genius, utilized the vast, rugged terrain of the Dragoon Mountains as his fortress. He perfected guerrilla warfare tactics, striking swiftly and vanishing into the unforgiving landscape, often leaving U.S. cavalry units bewildered and exhausted. His strategic brilliance lay in his intimate knowledge of the land, his ability to mobilize his warriors effectively, and his uncanny knack for evading capture. "He was a man of indomitable will," wrote General Oliver O. Howard, who eventually negotiated with Cochise, "and his word, once given, was as good as gold."

The Apache Wars, as they became known, were characterized by relentless U.S. military campaigns and equally tenacious Apache resistance. The U.S. Army, initially ill-equipped to fight a mobile, elusive enemy in such harsh conditions, gradually adapted. Generals like George Crook, known for his "Apache tactics," learned to fight the Apache on their own terms, using pack mules instead of wagons, and most controversially, employing Apache scouts against their own people. This strategy, though effective, sowed deep divisions within the Apache community and highlighted the immense pressure the U.S. exerted on them.

Despite their martial prowess, the Apache faced an insurmountable demographic and technological disadvantage. The constant pressure from settlers, miners, and the relentless military campaigns slowly eroded their numbers and resources. The U.S. government’s policy of forced removal to reservations, particularly the desolate San Carlos Reservation in Arizona – infamously dubbed "Hell’s Forty Acres" – became a primary tool for breaking Apache resistance. Conditions on these reservations were appalling: scarce food, rampant disease, corrupt agents, and the forced cessation of their traditional hunting and raiding practices. For a people whose identity was tied to freedom of movement and self-sufficiency, reservation life was a form of slow, agonizing death.

This indignity sparked renewed resistance from other leaders. Victorio, a Mimbreño Apache chief and contemporary of Cochise, launched one of the most desperate and brilliant campaigns of the Apache Wars. Repeatedly forced onto reservations like San Carlos, Victorio consistently rejected a life of confinement and dependency. In 1879, he led his band off the reservation, embarking on a two-year odyssey across New Mexico, Arizona, and northern Mexico, outmaneuvering and often defeating far larger U.S. and Mexican forces. His campaign was a testament to his tactical brilliance and his people’s sheer will to remain free. "I was born on the plains where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the sun," Geronimo would later say, articulating the shared Apache sentiment that drove Victorio. Victorio’s fight ended tragically in 1880, when Mexican troops cornered and killed him and most of his followers at Tres Castillos, Mexico.

The figure who arguably became the most globally recognized symbol of Apache resistance was Geronimo (Goyaałé). A Chiricahua Apache shaman and warrior, Geronimo’s personal tragedy – the murder of his family by Mexican soldiers – fueled a lifelong vendetta and an unyielding commitment to fighting for his people’s freedom. He was not a chief by birth, but his spiritual power, strategic acumen, and sheer audacity made him a revered and feared leader. From the 1870s through the mid-1880s, Geronimo and his small band of followers repeatedly broke out of reservations, leading U.S. and Mexican armies on grueling chases across thousands of miles of rugged terrain.

Geronimo’s escapes became legendary, frustrating the U.S. military and captivating the American public. His final, dramatic flight in 1885, with a mere 38 men, women, and children, triggered one of the largest military manhunts in U.S. history. General Nelson A. Miles eventually took command, deploying thousands of troops, heliographs for signaling, and Apache scouts, a strategy that highlighted the immense resources committed to subdue a handful of resilient fighters.

In September 1886, Geronimo, exhausted and isolated, finally surrendered to General Miles in Skeleton Canyon, Arizona. His surrender marked the official end of the Apache Wars and, symbolically, the close of the frontier era. His words, "I was a good warrior," captured the essence of his life. But the surrender came with a devastating betrayal: despite promises of a return to their homeland, Geronimo and the remaining Chiricahua Apaches, including those who had served as scouts for the U.S. Army, were sent as prisoners of war to Florida, then Alabama, and finally to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. They would never see their ancestral lands again.

The Apache leaders’ resistance against U.S. military expansion was a protracted, brutal, and ultimately tragic struggle. It was a fight not just for land, but for a way of life, for cultural identity, and for the fundamental right to self-determination. Their strategic brilliance, their unparalleled knowledge of the land, and their unwavering courage in the face of overwhelming odds earned them the grudging respect of their enemies and an enduring place in history.

The legacy of the Apache resistance is complex. It represents a profound testament to human resilience and the refusal to be subjugated. It also serves as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of unchecked expansionism, broken treaties, and cultural annihilation. Though their armed struggle ended, the spirit of the Apache people, forged in the crucible of this conflict, endures. Their story is a powerful narrative of defiance, a poignant echo of the untamed spirit that refused to bend, even as the world around them irrevocably changed.