The Enduring Tapestry: Anthropological Studies of Turtle Island Cultures

Anthropological inquiry into the myriad cultures of Turtle Island – a name rooted in various Indigenous creation stories, notably Anishinaabemowin and Haudenosaunee traditions, referring to the North American continent – unveils a profound, complex, and enduring human history. Far from a monolithic entity, Turtle Island represents a vibrant mosaic of nations, languages, spiritual beliefs, and sophisticated social structures, each deeply connected to specific ancestral lands. Contemporary anthropological studies, increasingly decolonized and Indigenous-led, move beyond the problematic "salvage ethnography" of the past, seeking to understand, honor, and support the living, evolving traditions and resilience of Indigenous peoples.

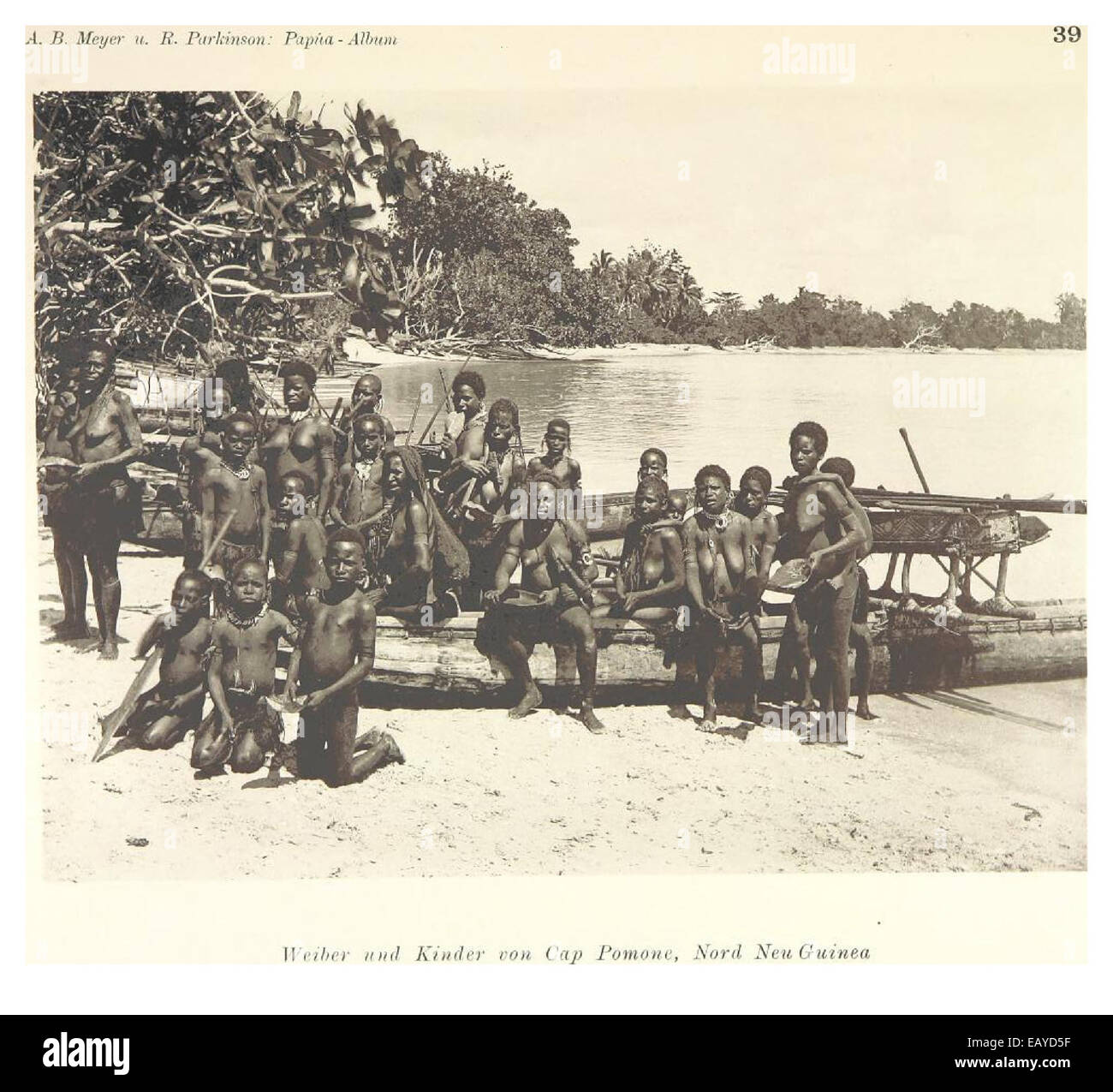

Historically, anthropology’s gaze upon Indigenous cultures was often complicit with colonial projects, categorizing and objectifying for external consumption, frequently under the assumption of impending cultural disappearance. Early ethnographers documented languages, rituals, and material culture, often in an extractive manner. However, the discipline has undergone a critical transformation, acknowledging its own role in perpetuating stereotypes and marginalization. Today, ethical anthropological engagement prioritizes collaboration, reciprocity, and Indigenous sovereignty, recognizing that the most profound insights emerge when research is "by us, for us, with us." This shift re-centers Indigenous voices, methodologies, and epistemologies, fostering a more respectful and relevant understanding of Turtle Island’s heritage.

A cornerstone of anthropological study across Turtle Island is the deep exploration of cosmology and oral traditions. The very concept of Turtle Island itself stems from creation narratives where a giant turtle provides the foundation for the earth, often involving a Muskrat or other animals diving to retrieve soil from the primordial waters. These stories, such as those of the Anishinaabe or Haudenosaunee, are not mere myths but profound frameworks for understanding the universe, humanity’s place within it, and moral imperatives. "Our stories are not just entertainment; they are our law, our history, our science, and our philosophy," notes Haudenosaunee scholar Rick Hill. Anthropologists meticulously document these oral traditions, working closely with knowledge keepers to preserve languages and narrative forms that embody centuries of wisdom. From the Diné (Navajo) creation stories detailing emergence from successive worlds to the rich spiritual narratives of the Kwakwaka’wakw of the Pacific Northwest, these cosmologies provide unique lenses through which to perceive time, space, and kinship.

Intrinsically linked to these worldviews is the profound connection to land, environment, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Indigenous cultures across Turtle Island have cultivated sophisticated, sustainable relationships with their environments for millennia. Anthropology has been crucial in documenting these intricate systems, revealing practices that prioritize reciprocity over extraction. For instance, studies among the Anishinaabe or Ojibwe highlight their deep knowledge of manoomin (wild rice), its growth cycles, and sustainable harvesting techniques that ensure its proliferation. Similarly, the sophisticated land management practices, including prescribed burns, of nations like the Karuk or Yurok in California, are now recognized as vital for forest health and biodiversity, challenging Western notions of "wilderness" as untouched by human hand. The concept of land as a living relative, not a resource to be owned, is a unifying theme. Anthropologists, often in collaboration with environmental scientists, now examine how TEK offers critical solutions to contemporary environmental crises, from climate change to biodiversity loss.

Social structures and governance on Turtle Island are remarkably diverse and complex, challenging simplistic classifications. Anthropological research has illuminated a spectrum of political organizations, from highly decentralized bands to elaborate confederacies. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations), established under the Kaianere’kó:wa (Great Law of Peace), stands as a testament to sophisticated governance. This democratic system, emphasizing consensus, balance, and long-term thinking (seven generations), has been studied extensively, with some scholars even suggesting its indirect influence on the formation of the United States Constitution. Elsewhere, studies of the matriarchal structures among various nations, where women held significant political, economic, and spiritual authority, offer alternatives to patriarchal Western models. Kinship systems, often extensive and highly prescriptive, dictate social roles, responsibilities, and resource distribution, forming the bedrock of community life.

The material culture and artistic expressions of Turtle Island cultures provide tangible links to spiritual beliefs, historical narratives, and social identity. From the intricate beadwork of the Plains nations, often depicting personal visions or tribal histories, to the monumental totem poles of the Pacific Northwest, carved with ancestral figures and clan crests, art is rarely merely decorative. Anthropological studies have documented the techniques, symbolism, and cultural significance of these crafts, tracing their evolution and adaptation over time. Pottery, weaving (e.g., Navajo rugs, Salish blankets), basketry, and ceremonial regalia are not static artifacts but living traditions, constantly reinterpreted by contemporary artists who blend ancestral knowledge with modern aesthetics. These studies highlight art’s role in cultural transmission, spiritual practice, and economic sustenance.

A critical area of contemporary anthropological focus is language revitalization. Centuries of colonial policies, including residential schools and forced assimilation, have pushed many Indigenous languages to the brink of extinction. Anthropologists, often in partnership with community linguists, have a crucial role in documenting remaining speakers, creating dictionaries, grammars, and language learning materials. However, the emphasis has shifted from mere documentation to active support for Indigenous-led revitalization initiatives. The loss of language is not just the loss of words; it is the loss of unique worldviews, epistemologies, and cultural nuances embedded within the linguistic structure. For example, many Indigenous languages are verb-based, reflecting a world of action and relationship rather than static nouns, fundamentally shaping how speakers perceive reality. Projects like the immersion schools for the Cherokee language or the efforts to revive Hul’q’umi’num’ (Coast Salish) demonstrate the profound commitment of communities to reclaim their linguistic heritage.

The evolution of anthropological studies on Turtle Island underscores a journey from observer to collaborator. The discipline is increasingly challenged to confront its own legacy and actively engage in decolonization efforts. This means supporting Indigenous self-determination, acknowledging land claims, and promoting the repatriation of cultural artifacts and ancestral remains. It means recognizing Indigenous peoples not as subjects of study, but as intellectual leaders and knowledge holders whose insights are vital for addressing global challenges. The future of anthropology on Turtle Island is one where research serves the needs and aspirations of Indigenous communities, contributing to their cultural continuity, political sovereignty, and well-being.

In conclusion, the anthropological study of Turtle Island cultures is a dynamic and evolving field, revealing the extraordinary depth, diversity, and resilience of Indigenous peoples across North America. From the foundational creation stories that root humanity to the earth, through intricate systems of environmental stewardship and governance, to vibrant artistic expressions and determined language revitalization efforts, these cultures offer invaluable lessons. As anthropology continues its journey of decolonization, it increasingly serves as a bridge for understanding, ensuring that the enduring wisdom and vibrant contemporary realities of Turtle Island are recognized, respected, and celebrated for generations to come.