Ancient Pueblo Pottery Techniques: Traditional Methods Still Used Today

In the arid landscapes of the American Southwest, a profound legacy endures, one shaped by hands of earth and fire. For over two millennia, the Pueblo peoples have crafted pottery, not merely as utilitarian objects, but as expressions of culture, spirituality, and a deep connection to their ancestral lands. What is remarkable is that many of the ancient techniques, honed over generations, are not relics confined to museums, but living traditions vigorously practiced by contemporary Pueblo potters today. This continuity speaks volumes about the resilience of a culture and the timeless artistry embedded in every coil, every brushstroke, and every firing.

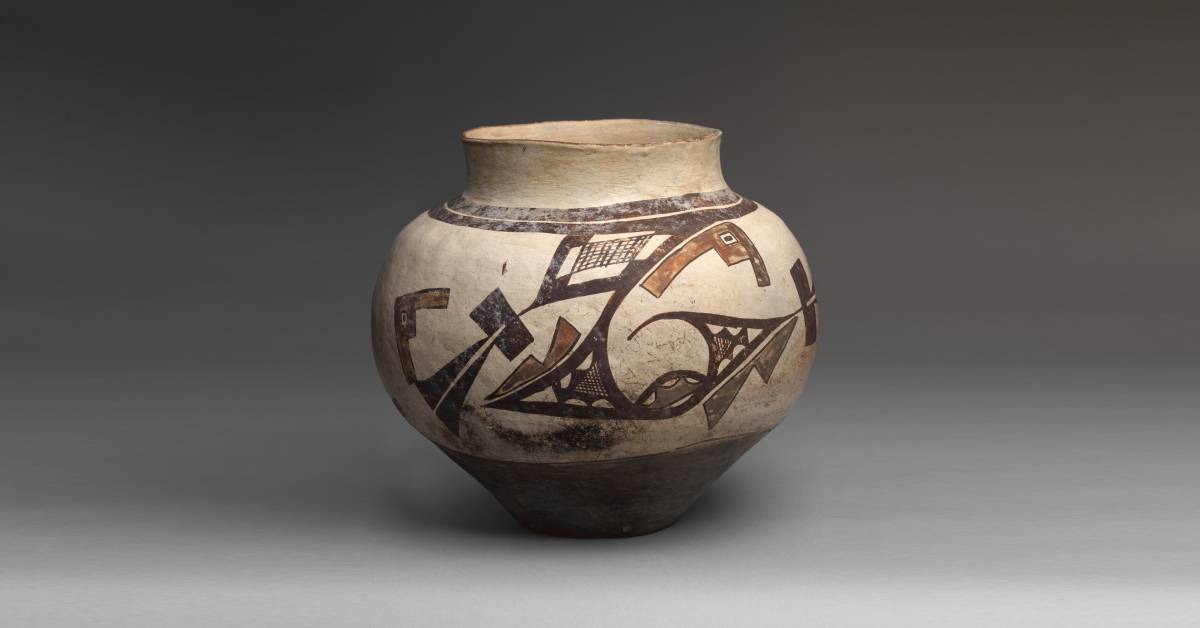

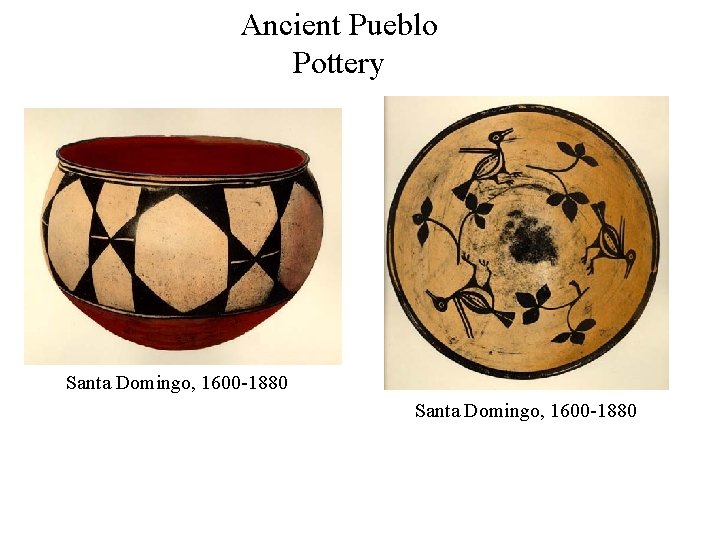

The story of Pueblo pottery begins long before European contact, with archaeological evidence tracing its origins back nearly 2,000 years. Early Puebloans, or Ancestral Puebloans, developed sophisticated methods for transforming raw clay into durable vessels, essential for storing water, cooking food, and holding seeds. Over centuries, these functional pieces evolved, incorporating intricate designs and forms that reflected their worldview, their ceremonies, and their daily lives. Today, potters from communities like Acoma, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Hopi, and Zuni pueblos continue to draw directly from this ancient wellspring of knowledge, demonstrating an unwavering commitment to the methods that define their heritage.

The Earth’s Embrace: Sourcing and Preparation

The journey of a Pueblo pot begins, as it always has, with the earth itself. Potters traditionally embark on journeys to specific, often sacred, clay deposits within their ancestral lands. These sites are not chosen arbitrarily; they are known for yielding clays with particular qualities – plasticity, color, and firing characteristics. "Finding the right clay is like finding a part of your own spirit," explains a hypothetical elder potter from Acoma, whose family has used the same clay source for generations. "It connects you to those who came before."

Once excavated, the raw clay is not ready for use. It must be carefully prepared, a laborious process that ensures the final pot’s strength and integrity. Large lumps are broken down, often pounded with stones, then soaked in water to soften. Impurities like rocks and organic matter are meticulously removed by hand or by sifting through screens. Crucially, temper is added. Temper, an aggregate material, prevents the clay from cracking during drying and firing by reducing shrinkage and increasing thermal shock resistance. Ancient Puebloans discovered that crushed shards of old pottery (sherd temper), volcanic ash, or sand were ideal. The choice of temper is often specific to a pueblo or even a family tradition, contributing to the unique character of their pottery. This careful blend of clay and temper, known only through centuries of trial and error, is a fundamental secret passed down through oral tradition and hands-on teaching.

The Coil and the Curve: Building the Vessel

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of ancient Pueblo pottery, still universally practiced today, is the coiling method. Unlike cultures that adopted the potter’s wheel, Pueblo potters have always built their vessels by hand, a testament to their skill and patience. The process begins with forming a flat clay base, either by pressing a disc into a shallow mold or shaping it by hand. From this base, long, rope-like coils of prepared clay are progressively added, one on top of the other.

Each coil is carefully pinched and blended into the one below it, gradually building the walls of the pot upwards. The potter uses their fingers, often aided by simple tools like gourds or corncobs, to smooth the seams and shape the vessel, constantly rotating it and assessing its form. This method allows for an incredible diversity of shapes and sizes, from small bowls to monumental storage jars. The absence of a wheel means each pot carries the unique imprint of its maker’s hands, a subtle asymmetry that is prized as a mark of authenticity and human touch. This slow, meditative process imbues the pot with a palpable sense of human connection, a direct lineage from maker to material.

Sculpting and Smoothing: The Art of Refinement

Once the basic form is coiled, the pot undergoes a critical stage of refinement. The walls, initially thick and uneven, are thinned and shaped using scraping tools made from dried gourds, pieces of metal, or even old credit cards by modern potters. This process not only refines the vessel’s aesthetic but also strengthens its structure. The potter works to achieve a uniform thickness and a balanced, elegant silhouette.

Following scraping, many Pueblo pots, particularly those destined for a lustrous finish, undergo burnishing. This technique involves rubbing the surface of the leather-hard clay with a smooth, hard stone, often a river stone or a piece of hematite. The pressure compresses the clay particles, closing the pores and creating a naturally glossy, almost glass-like surface without the use of glazes. This painstaking process, which can take hours, is a hallmark of pottery from pueblos like Santa Clara and San Ildefonso, resulting in the iconic polished red and blackware. Alternatively, a "slip" – a thin liquid suspension of finely sieved clay, often colored – may be applied to the surface as a base coat for painting or to achieve a specific hue.

Whispers of the Ancients: Pigments and Patterns

The decorative elements on Pueblo pottery are far more than mere embellishments; they are visual narratives, symbols imbued with deep cultural and spiritual significance. The pigments used are, like the clay itself, sourced from the natural world. Mineral pigments, such as iron oxides for reds and browns, or ground hematite for a rich black, are common. For the distinctive deep black used in many designs, particularly on burnished red or white slips, a vegetal paint made from the Rocky Mountain beeweed ( Cleome serrulata) is often employed. This plant is boiled down to a thick, dark syrup, which carbonizes during firing to produce a permanent black.

The brushes used for painting are equally traditional: strips of yucca leaf, chewed or scraped at one end to create fine bristles. These natural brushes allow for remarkable precision, enabling potters to execute intricate geometric patterns, stylized animals (like deer or birds), cloud and rain symbols, or representations of corn and other sacred elements. Designs are often passed down through families, though individual potters also introduce innovations. Each symbol carries meaning: the spiral might represent the journey of life, the stepped motif, a cloud or a mountain. "Every line tells a story, a prayer for rain, a thanks for the harvest," says a potter from Zuni, emphasizing the sacred aspect of their designs. The application of these designs is not just artistic but an act of storytelling and cultural transmission.

The Fiery Transformation: Firing Techniques

The final, and perhaps most unpredictable, stage in the creation of a Pueblo pot is firing. This ancient process transforms the fragile, sun-dried clay into a hard, durable ceramic. Most traditional Pueblo pottery is fired outdoors, without kilns, using methods that have remained virtually unchanged for centuries.

Open-air firing involves stacking pots on a grid or platform, often made of old pot shards, and surrounding them with fuel. Cedar bark, wood, and dried animal dung (particularly horse or cow dung) are preferred fuels, known for their consistent heat and slow burn. In some traditions, particularly for blackware, pots are fired in shallow pits dug into the ground. The pots are carefully arranged, covered with fuel, and then sometimes topped with metal sheets or more dung to control oxygen flow.

The temperature reached in these firings can range from 1200 to 1800 degrees Fahrenheit (650 to 980 degrees Celsius), achieved through the intuitive knowledge of the potter, who monitors the flames and smoke. The atmosphere during firing dictates the final color. An "oxidizing" atmosphere, with ample oxygen, results in reds, oranges, and browns, as iron impurities in the clay are fully oxidized. A "reducing" atmosphere, created by limiting oxygen flow (e.g., by smothering the fire with dung or metal), causes carbon from the smoke to penetrate the clay and any organic pigments, resulting in the characteristic glossy black of Santa Clara or San Ildefonso blackware. This delicate balance of heat and atmosphere makes each firing an act of faith, a moment where the pot’s true spirit is revealed. The unpredictable nature of outdoor firing means that not every pot survives, adding to the mystique and value of those that do.

The Enduring Flame: Why Tradition Persists

In an era of mass production and rapid technological advancement, the steadfast commitment of Pueblo potters to these ancient, labor-intensive techniques is a powerful statement. Why do they persist? The reasons are multifaceted and deeply rooted in cultural identity.

For many, it is a direct connection to their ancestors, a way of honoring and continuing a lineage that stretches back thousands of years. "When I dig the clay, when I coil the pot, I feel the hands of my grandmother and her grandmother before her," says a young potter from Santa Clara. "It’s not just making a pot; it’s carrying on our people’s story." The techniques themselves are an embodiment of cultural knowledge, passed down through observation, practice, and storytelling within families.

Beyond cultural preservation, the traditional methods yield a distinctive aesthetic quality that cannot be replicated by modern industrial processes. Each hand-coiled, stone-polished, and open-fired pot is unique, bearing the subtle imperfections and variations that are hallmarks of true craftsmanship. This authenticity is highly valued by collectors and enthusiasts worldwide, providing economic sustainability for many Pueblo communities. The slow, deliberate pace of traditional pottery making also offers a spiritual dimension, allowing for contemplation and a deep engagement with the materials and process. It is a testament to the idea that some things are best done slowly, with intention and respect.

Challenges and Triumphs

The continuation of these ancient practices is not without its challenges. Sourcing traditional materials can be difficult due to land use changes or environmental regulations. The time-consuming nature of the work makes it difficult to compete with inexpensive, mass-produced pottery. There’s also the challenge of attracting younger generations to dedicate themselves to a craft that demands years of apprenticeship and often yields a modest income.

However, the triumphs far outweigh the difficulties. Pueblo pottery has garnered international acclaim, celebrated in museums and galleries worldwide. Educational initiatives and cultural programs within the pueblos are actively working to ensure the transmission of knowledge to new generations. The increasing appreciation for handmade, culturally significant art has created a vibrant market, allowing traditional potters to thrive.

In conclusion, the ancient Pueblo pottery techniques are far more than historical footnotes; they are a vibrant, living heritage. From the reverent sourcing of clay from ancestral lands to the intuitive control of fire, each step in the process is a direct link to a past that continues to inform the present. The enduring practice of coiling, stone-polishing, natural pigment painting, and open-air firing by contemporary Pueblo potters is a testament to the resilience of their culture, the profound beauty of their art, and the timeless wisdom embedded in the earth and hands that shape it. These pots, born of ancient methods, stand as powerful symbols of continuity, artistry, and an unbreakable bond between a people and their sacred land.