Echoes in the Stone and Sky: Unearthing Ancient Native American Astronomical Wisdom

For centuries, the prevailing narrative in Western thought often relegated the scientific and intellectual achievements of indigenous cultures to the realm of myth or simple folklore. Yet, beneath the vast North American sky, long before European navigators charted their courses by distant stars, sophisticated societies were meticulously mapping the cosmos, embedding their profound astronomical knowledge into architecture, art, and the very fabric of their spiritual lives. From the sun-drenched canyons of the Southwest to the sprawling mounds of the Mississippi Valley and the windswept plains, ancient Native Americans were accomplished sky-watchers, their observations driven by a blend of practical necessity, spiritual reverence, and an insatiable curiosity about the universe.

This article delves into the remarkable depth of ancient Native American astronomical knowledge, exploring the evidence etched in stone, woven into oral traditions, and rediscovered through the burgeoning field of archaeoastronomy. It aims to illuminate a scientific heritage that is as precise as it is poetic, challenging misconceptions and revealing a profound connection between humanity and the celestial dance.

The "Why": Cosmos as Calendar, Compass, and Creed

Unlike modern astronomy, which often operates in a detached scientific sphere, ancient Native American sky-watching was intrinsically interwoven with daily life, survival, and spiritual identity. The cosmos was not merely a distant spectacle but a dynamic, living entity that dictated agricultural cycles, hunting seasons, ceremonial calendars, and even societal structures.

For agrarian societies, understanding the precise timing of solstices and equinoxes was paramount. Planting and harvesting relied on accurate seasonal markers, making the sun’s journey across the sky a literal lifeline. Hunters and gatherers used lunar cycles and star patterns to predict animal migrations and navigate vast territories. Beyond practicality, the movements of celestial bodies were seen as manifestations of powerful deities or ancestral spirits, influencing earthly events and offering guidance. The sky was a grand narrative, a sacred text continually unfolding, and interpreting its messages was the responsibility of dedicated sky-watchers, priests, and shamans who held positions of immense respect within their communities.

"For many Native cultures," notes archaeoastronomer John Carlson, "the Earth and sky were not separate entities but interconnected parts of a sacred whole. Understanding the celestial rhythms was understanding the divine order." This holistic worldview meant that astronomical observation was not just science; it was an act of profound spiritual engagement, a way of maintaining harmony with the universe.

Stones That Speak to the Stars: Archaeological Wonders

The most compelling evidence of ancient Native American astronomical prowess lies in the archaeological record, particularly in structures deliberately aligned with celestial events.

One of the most famous examples is the Fajada Butte Sun Dagger in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, a UNESCO World Heritage site and a nexus of the ancient Pueblo (Anasazi) culture. Here, three precisely placed stone slabs channel sunlight onto a large spiral petroglyph carved into the cliff face. At the summer solstice, a "dagger" of light pierces the center of the largest spiral. At the winter solstice, two daggers frame it. During the equinoxes, one dagger bisects a smaller spiral. This intricate device also marked major lunar standstills, demonstrating a profound understanding of both solar and lunar cycles. Chaco Canyon itself, with its massive "Great Houses" like Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl, reveals numerous alignments with solstices, equinoxes, and lunar extremes, suggesting the entire canyon was conceived as a cosmic observatory. The kivas – circular, subterranean ceremonial chambers – often had specific openings or orientations that allowed sunlight or moonlight to mark significant dates.

Further east, the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site in Illinois, once the largest city north of Mesoamerica, boasts its own astronomical marvel: Woodhenge. Discovered in the 1960s, Woodhenge consists of multiple circles of large, evenly spaced timber posts. Archaeologists have identified five distinct Woodhenges built over several centuries, the largest comprising 72 posts. These circles were precise calendrical devices. At the spring and fall equinoxes, the sun rises directly behind a specific post when viewed from the center of the circle. At the summer and winter solstices, the sun rises over other designated posts. Woodhenge was crucial for timing Cahokia’s agricultural cycles and massive ceremonial gatherings, underscoring the sophisticated engineering and astronomical knowledge of the Mississippian people.

Across the Great Plains, hundreds of enigmatic stone circles known as Medicine Wheels dot the landscape. While their exact functions varied among different tribes, many, like the Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, clearly served astronomical purposes. This wheel, with its central cairn, 28 spokes, and several outer cairns, aligns with the summer solstice sunrise and sunset, as well as the rising points of significant stars like Aldebaran, Rigel, and Sirius. These alignments suggest they were used for calendrical purposes, ceremony, and perhaps even as teaching tools for star lore.

Beyond Alignments: Charting Stars and Cycles

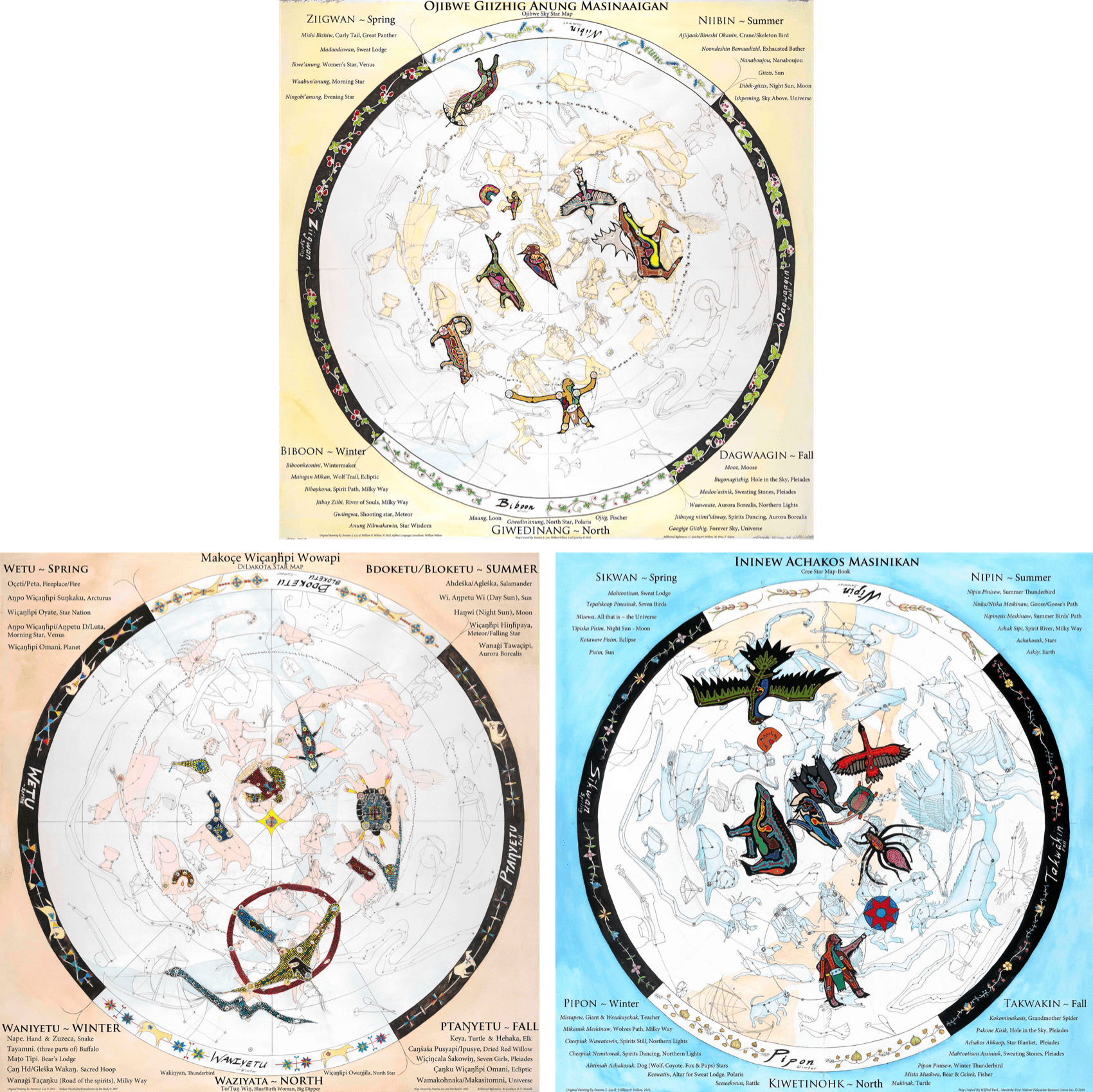

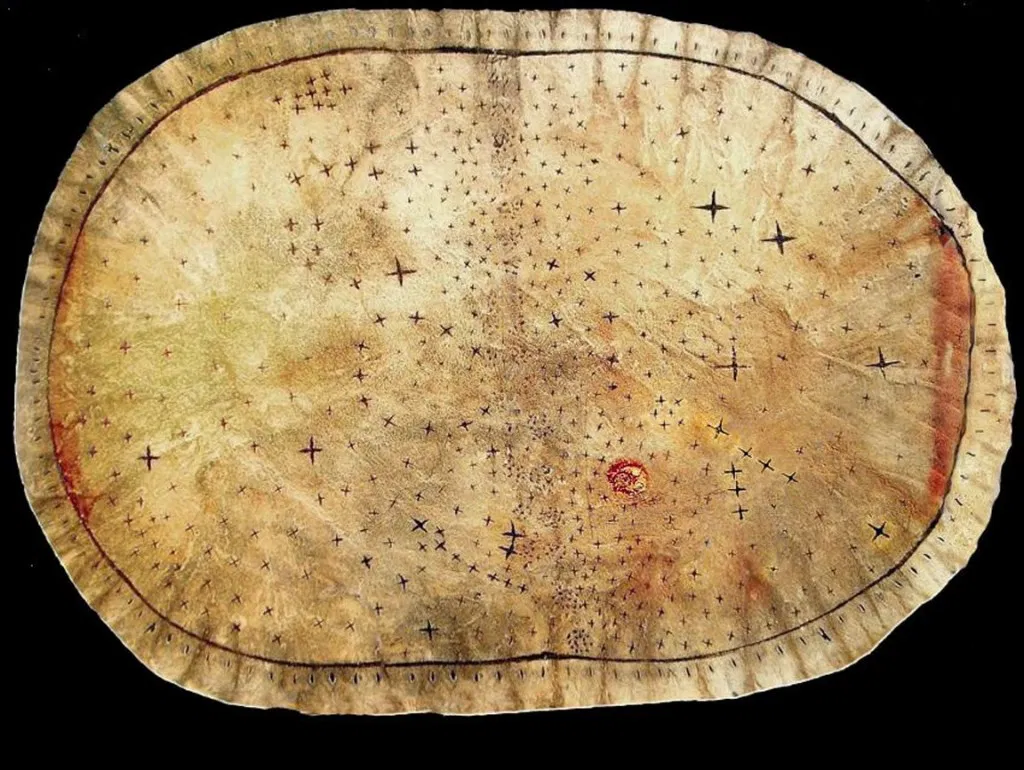

Native American astronomy extended beyond solar and lunar alignments. Many cultures possessed rich traditions of star-gazing, identifying constellations, and tracking planetary movements.

The Pawnee people of the Great Plains, for instance, had an exceptionally complex cosmology centered around stars. Their lodges were built as microcosms of the universe, with smoke holes representing the North Star and poles aligned to cardinal directions. Their elaborate star charts, passed down through oral traditions, identified constellations corresponding to various deities and spirits. The rising and setting of certain stars dictated ceremonial times and planting schedules. For the Pawnee, the Morning Star (Venus) was particularly significant, often associated with fertility and creation.

The Zuni people of the Southwest had dedicated "Sun Priests" who meticulously tracked the sun’s position against horizon landmarks. By observing the daily shift of sunrise and sunset points, they could precisely determine the solstices and equinoxes, often marking these points with stone cairns or notches on distant mesas. This "horizon astronomy" was a simple yet incredibly effective method, refined over millennia of observation.

While direct evidence of telescopic use is absent, the accuracy of their observations suggests generations of patient, naked-eye sky-watching. They understood the 19-year Metonic cycle of the moon (which brings lunar phases back to roughly the same calendar dates), as evidenced by the Fajada Butte Sun Dagger’s lunar alignments. They tracked the complex retrograde motion of planets like Mars and Venus, integrating these observations into their mythologies and predictive models.

The Living Legacy: A Call for Appreciation

The profound astronomical knowledge of ancient Native Americans was largely dismissed or misunderstood by early European colonizers, who often viewed indigenous cultures through a lens of intellectual inferiority. This led to the suppression of traditional practices and the loss of invaluable knowledge. Yet, through the dedicated work of archaeologists, anthropologists, and, crucially, Native American elders and scholars, this rich heritage is being reclaimed and reinterpreted.

The field of archaeoastronomy, which bridges archaeology and astronomy, has been instrumental in deciphering the celestial codes embedded in ancient sites. It has revealed that these were not random arrangements of stones or simple dwellings, but sophisticated observatories and ceremonial centers designed to connect earthly life with the cosmic order.

Understanding this ancient wisdom is more than an academic exercise. It offers a vital perspective on human ingenuity, the diverse paths to scientific discovery, and the profound, enduring connection between culture, spirituality, and the natural world. It challenges the Eurocentric view of scientific development and reminds us that sophisticated knowledge systems flourished independently across the globe.

As we continue to gaze at the night sky, illuminated by distant stars, it is imperative to remember the ancient sky-watchers of North America. Their legacy, etched in stone and passed through generations, speaks of a deep reverence for the cosmos, a meticulous scientific inquiry, and a holistic worldview where the universe was not just observed but profoundly experienced. Their wisdom reminds us that the greatest observatories are not always built with glass and steel, but sometimes with simple stones, carefully placed, under an open, watchful sky.