Echoes of Earth: Ancient Adobe Cities Still Live and Breathe

In a world relentlessly pushing towards the new, where steel and glass define our skylines, there exist venerable structures that defy the march of time. These aren’t forgotten ruins but vibrant, multi-story adobe complexes, often hundreds or even a thousand years old, that continue to house communities, preserve ancient traditions, and stand as living testaments to human ingenuity and resilience. Predominantly found in the arid landscapes of the American Southwest, these earth-built skyscrapers represent an architectural lineage stretching back to pre-Columbian eras, offering a profound connection to the past that is not merely observed but actively lived.

The story of these ancient multi-story adobe structures begins with the Ancestral Puebloans, often referred to as Anasazi, who inhabited the Four Corners region of the United States. Around 700 to 1300 AD, these sophisticated societies began to transition from semi-subterranean pit houses to above-ground, multi-room, multi-story dwellings known as pueblos. The material of choice was, and remains, adobe – a mixture of earth, water, and organic materials like straw or grass, sun-dried into bricks or used as a puddled, monolithic mass. This humble material, abundant in the desert, proved to be an exceptional insulator, keeping interiors cool during scorching summers and warm through freezing winters.

But why multi-story? The reasons were manifold. Defensive positioning was paramount; elevated structures offered vantage points and made attacks more difficult. Communal living fostered social cohesion and shared labor. And as populations grew, building upward maximized limited, often sacred, land. These early pueblos, such as those found at Mesa Verde or Chaco Canyon, were often built into cliffs or on mesa tops, reaching impressive heights of three to five stories, sometimes even more. While many of these monumental sites are now protected archaeological parks, several have remained continuously inhabited, their adobe walls absorbing centuries of stories, rituals, and daily life.

The construction of these adobe marvels is a masterclass in passive architecture. Thick adobe walls, often two to three feet deep, provide immense thermal mass, moderating internal temperatures naturally. Small windows, strategically placed, minimize heat gain in summer and loss in winter. Roofs are typically constructed from large wooden beams called vigas, often pinyon or juniper, spanning the rooms, overlaid with smaller sticks (latillas), brush, and then a thick layer of mud and earth. This layered approach not only provides insulation but also forms a sturdy, walkable surface for the story above, creating a terraced effect that defines the iconic pueblo aesthetic.

Beyond their practical benefits, the design of these pueblos reflects a deep understanding of community and cosmology. Central plazas often served as gathering spaces, while subterranean or semi-subterranean circular chambers known as kivas were, and still are, vital spiritual and ceremonial centers. These structures were not just buildings; they were living organisms, evolving with the community, with new rooms and levels added over generations, creating organic, interconnected complexes that are both functional and deeply symbolic.

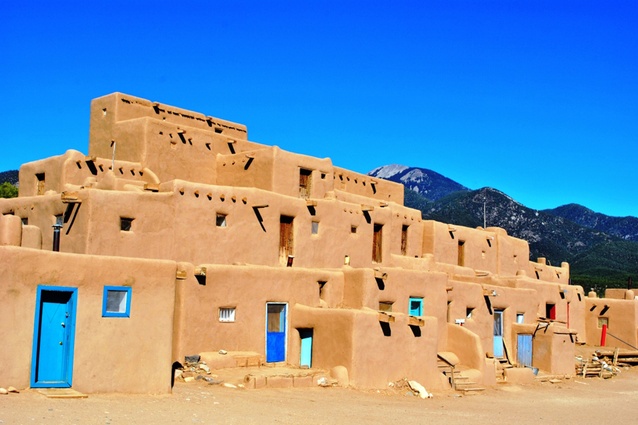

Perhaps the most famous and enduring example is Taos Pueblo in northern New Mexico. A UNESCO World Heritage site and a National Historic Landmark, Taos Pueblo is believed to be the oldest continuously inhabited community in North America, with parts of its main structures dating back over 1,000 years. Its distinctive terraced adobe buildings, rising five stories high, are an iconic image of indigenous architecture. The community, known as the Red Willow People, still lives within these ancient walls, largely eschewing modern utilities like electricity and running water within the historic pueblo itself, though modern homes exist outside. "The walls are like our ancestors," one elder once reportedly mused, "watching over us, guiding us. They are not just mud; they are our history, our spirit." This sentiment encapsulates the profound connection residents have to their homes, which are seen not merely as shelters but as extensions of their identity and heritage.

Another extraordinary example is Acoma Pueblo, often called "Sky City," perched atop a magnificent 367-foot sandstone mesa in New Mexico. Inhabited for over 800 years, Acoma is one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in the United States. Its remote, defensive location made it an unconquerable fortress for centuries. While many residents now live in modern homes at the base of the mesa, the ancient pueblo remains a vibrant cultural heart, with several families still residing there permanently. The houses, some three stories high, are built directly from the mesa’s clay, blending seamlessly into the landscape. Access to the mesa was historically via hand-cut steps and trails, a testament to the ingenuity and fortitude of its people.

Further west, on the Hopi Mesas in Arizona, Old Oraibi stands as one of the oldest settlements in North America, continuously inhabited for possibly over 1,100 years. While not as overtly multi-story as Taos or Acoma, its ancient stone and adobe homes, built on the mesa top, represent an unbroken lineage of tradition and spirituality. The Hopi people, renowned for their intricate culture and spiritual practices, have maintained their way of life within these ancestral homes, adapting to change while fiercely preserving their identity.

The endurance of these adobe cities speaks volumes about their inherent sustainability and the cultural tenacity of their inhabitants. Built from local materials, they leave a minimal ecological footprint. Their thick walls provide natural climate control, reducing the need for artificial heating or cooling. More importantly, they are anchors of identity. For the Pueblo peoples, these homes are not mere structures but living beings, imbued with the spirits of their ancestors and the stories of their lineage. They are tangible links to a past that informs the present and guides the future.

However, living in these ancient structures is not without its challenges. Adobe, while resilient, requires constant maintenance. Rain and wind can erode the walls, necessitating regular replastering and repairs, often performed communally. Balancing the desire for modern amenities like electricity, plumbing, and internet with the preservation of traditional lifeways and the structural integrity of ancient buildings is an ongoing negotiation. Tourism, while providing economic benefits, also brings its own set of pressures, requiring communities to manage access while protecting their privacy and sacred spaces.

Despite these challenges, the continued habitation of these ancient multi-story adobe structures is a powerful declaration. They are not static museums but dynamic, evolving communities that embody a profound connection between people and place. They remind us that true sustainability lies not just in new technologies but in respecting and learning from the wisdom of ancient builders. In a world often disconnected from its roots, these living adobe cities offer a profound and inspiring testament to the enduring human spirit, the wisdom of ancestral knowledge, and the timeless beauty of building with the earth itself. They stand, generation after generation, as silent yet eloquent witnesses to a heritage that refuses to be relegated to history books, continuing to shelter, nurture, and inspire.