Masters of the Tides: Ancient Fishing Techniques of the Pacific Northwest Tribes

In the verdant, rain-swept expanse of the Pacific Northwest, where towering ancient forests meet the restless embrace of the ocean, a civilization thrived for millennia, intricately woven into the very fabric of its environment. The Indigenous peoples of this region—the Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Coast Salish, and many others—were not merely inhabitants of this rich landscape; they were its profound stewards, masters of its intricate ecosystems, and, perhaps most notably, unparalleled innovators in the art and science of fishing. Their ancient techniques, refined over thousands of years, represent a sophisticated understanding of marine biology, engineering, and sustainable resource management, far beyond what modern societies often attribute to so-called "primitive" cultures.

For these tribes, fishing was far more than a means of sustenance; it was a spiritual practice, a cornerstone of their cultural identity, and the bedrock of their complex social structures. The annual salmon runs, the bounty of halibut in deep waters, the shimmering schools of herring, and the rich clam beds were gifts from the Creator, demanding respect, ceremony, and a profound commitment to reciprocity. Their fishing methods, passed down through generations via oral traditions and practical apprenticeship, were a testament to ingenuity, patience, and an intimate knowledge of the natural world.

The Sacred Salmon: Lifeblood of a Civilization

No single species held greater importance than the salmon, revered as a sacred being that sacrificed itself annually to feed the people. Five species—Chinook (King), Sockeye (Red), Coho (Silver), Pink (Humpback), and Chum (Dog)—returned from the ocean to spawn in the rivers and streams, providing a predictable, abundant, and vital food source. The sheer volume of salmon necessitated highly efficient and diverse harvesting techniques.

One of the most impressive and widespread methods was the construction of weirs and traps. Weirs were elaborate fences or dams, often stretching across entire rivers, built from stakes, interwoven branches, and stone. Designed to funnel migrating salmon into specific areas or holding pens, these structures allowed for selective harvesting. As one elder from the Coast Salish tradition might explain, "Our ancestors understood the salmon’s journey, not just its path. The weir was a doorway, not a wall. We took what we needed, always leaving enough for the next generation, and enough for the bears and the eagles." These weren’t simple barriers; they were sophisticated hydrological engineering marvels, designed to withstand powerful currents while remaining permeable enough to allow some fish to pass upstream, ensuring the continuation of the run.

Beyond large weirs, smaller, intricately woven basket traps were deployed in eddies and along riverbanks, often baited or placed in strategic current flows. Tidal traps, another ingenious solution, utilized the ebb and flow of the ocean. Constructed in bays and estuaries, these stone or wooden fences would guide fish into enclosed areas at high tide; as the tide receded, the fish would be stranded, easily collected. These traps were often communal, reflecting the cooperative nature of these societies, where the bounty was shared among families and clans.

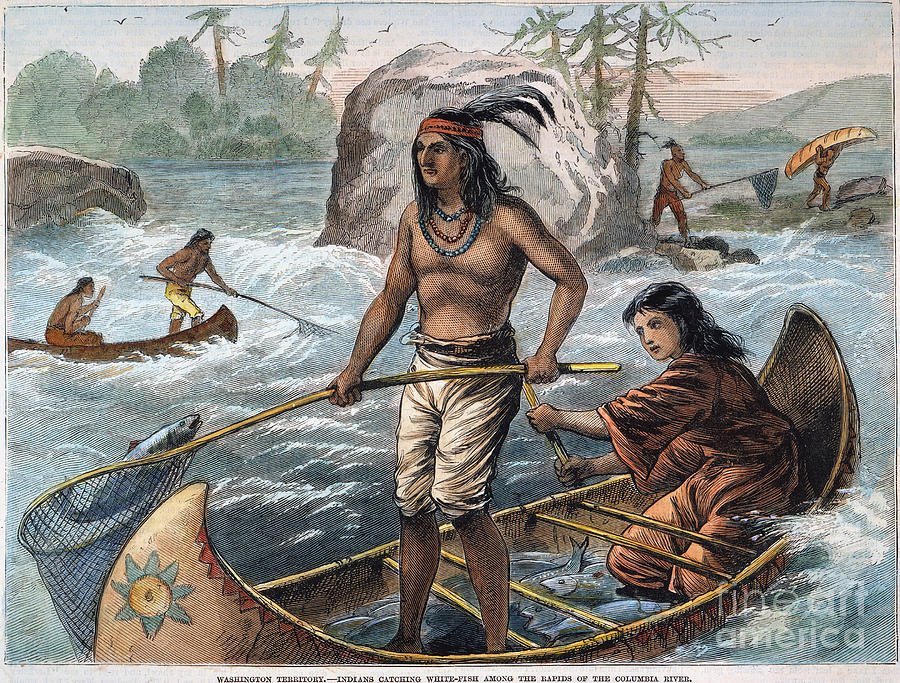

For active fishing, dip nets and seine nets were employed with great skill. Dip nets, often large and attached to long poles, were used in rapids or at the base of waterfalls where salmon would rest or attempt to leap. Seine nets, sometimes hundreds of feet long, were woven from cedar bark fibers, nettle, or sinew, weighted with stones and floated with wooden or bark buoys. Teams of canoes would deploy these nets, encircling schools of fish in estuaries or open water. The strength and flexibility of cedar bark fibers, often processed to create exceptionally durable cordage, were critical to the success of these large-scale netting operations.

Simpler, yet equally effective, tools included spears and gaffs. Spears, with their barbed bone or antler points, were used from canoes or along riverbanks. Gaffs, essentially long poles with a sharp, hooked point, allowed fishers to snag salmon as they swam past. The precision and patience required for these methods speak to the intimate connection between the fisher and their prey.

Beyond Salmon: Harvesting the Ocean’s Depths

While salmon were paramount, the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest also mastered the harvest of a vast array of other marine life, each requiring specialized tools and techniques.

Halibut, a massive flatfish dwelling in deep ocean waters, demanded ingenuity and courage. Fishermen would venture far offshore in their sturdy cedar canoes, navigating by ancestral knowledge of currents, landmarks, and celestial bodies. Their most iconic tool for halibut fishing was the two-piece halibut hook, typically carved from yellow cedar or yew wood. These hooks were often elaborately carved with animal figures (such as an octopus or a shaman) believed to attract the fish or appease the spirits of the sea. The hook’s design was ingenious: a straight shank and a barb, lashed together with sinew or spruce root, designed to fit perfectly into the halibut’s mouth, catching on its jaw bone. Unlike a modern J-hook, this design minimized injury to other species and allowed for easier release of smaller fish. Baited with octopus, herring, or other fish, these hooks were lowered on lines woven from cedar bark, nettle, or even whale baleen, weighted with carefully chosen stones.

Herring and eulachon (candlefish), small oily fish that arrived in vast schools, were critical for their rich oil, a prized commodity for food, medicine, and trade. Herring rakes, long poles embedded with sharp bone or antler points, were swept through dense schools of fish, impaling dozens at a time. Nets were also used, and the sheer volume of these fish meant that entire communities would gather to process them, rendering their oil—a liquid gold that was traded far inland along ancient "grease trails."

The intertidal zones were also a vital pantry. Clams, mussels, and oysters were harvested in abundance. Women, often the primary gatherers of shellfish, used digging sticks made from yew or other hard woods to efficiently unearth clams from sandy or muddy beaches. Recent archaeological research has revealed the existence of "clam gardens"—purposefully constructed rock walls at the low tide line that flattened and expanded the productive clam habitat. These gardens, actively maintained by Indigenous communities for thousands of years, demonstrate a profound understanding of aquaculture and ecological management, increasing clam productivity by as much as 400% in some areas.

Ingenious Tools and Materials

The resourcefulness of PNW tribes in crafting their fishing gear from natural materials is awe-inspiring. Red cedar, known as the "tree of life," was indispensable. Its wood was used for canoes, floats, and the structural elements of weirs and traps. Its inner bark was processed into incredibly strong and flexible ropes and lines for nets and fishing tackle. Bone and antler were carved into barbed spear points, gaff hooks, and the intricate barbs of halibut hooks. Stone was shaped into net weights, anchor stones, and tools for processing fish. Shells, particularly those of mussels, were sometimes sharpened and used as lures or components of hooks.

Harpoons for marine mammals like seals, sea lions, and even whales (for tribes like the Nuu-chah-nulth) were marvels of engineering. These typically featured a detachable, barbed point made of bone or antler, connected to the line, which would detach from the shaft upon impact. This allowed the shaft to float, marking the animal, while the line remained attached to the point embedded in the prey, preventing it from escaping.

Sustainability and Sacred Reciprocity

The enduring success of these ancient fishing techniques was not merely about technological prowess; it was rooted in a deep-seated philosophy of sustainability and respect. The concept of "leaving enough" was paramount. Harvests were timed to coincide with peak abundance but were never allowed to deplete the stock. The "First Salmon Ceremony," practiced by many tribes, exemplified this reverence. The first salmon caught each season was treated with immense respect, celebrated, and often returned to the river after a symbolic meal, its bones carefully placed back in the water to show gratitude and ensure its spirit would return the following year.

This spiritual connection reinforced practical conservation. Fishermen knew the precise timing of each run, the specific locations for different species, and the nuances of tides and currents. This intimate, localized ecological knowledge allowed them to harvest efficiently without overexploiting resources. The clam gardens, the selective nature of weirs, and the careful management of fishing sites all point to a deliberate, active, and successful approach to environmental stewardship that sustained their communities for thousands of years.

An Enduring Legacy

The ancient fishing techniques of the Pacific Northwest tribes are not relics of a bygone era. While modern technologies have altered the landscape of fishing, the knowledge, values, and spiritual connection to the waters endure. Today, Indigenous communities continue to practice many of these traditional methods, often as part of cultural revitalization efforts, and to assert their inherent fishing rights.

The legacy of these ancient masters of the tides reminds us of humanity’s profound capacity for innovation, adaptation, and sustainable living when guided by deep respect for the natural world. Their ingenious techniques, woven into the very fabric of their cultural identity, offer invaluable lessons for contemporary societies grappling with the challenges of resource management and environmental stewardship. The rivers and oceans of the Pacific Northwest continue to whisper tales of cedar canoes gliding silently, of nets teeming with silver, and of a people who understood that to truly thrive, one must first learn to listen to the water.