Echoes of the Buffalo Soldiers: African American Cavalry and the Crucible of the Indian Wars

The vast, untamed expanse of the American West, a landscape etched with the promise of expansion and the harsh realities of conflict, served as a crucible for countless narratives. Among the most compelling, yet often marginalized, are the stories of the African American cavalry units, affectionately known as the "Buffalo Soldiers." Formed in the tumultuous aftermath of the Civil War, these resilient men served on the front lines of the Indian Wars, forging a legacy of courage, discipline, and perseverance against a backdrop of racial prejudice and relentless duty. Their contributions were instrumental in shaping the frontier, yet their sacrifices and triumphs often remained in the shadows of historical memory.

The genesis of the Buffalo Soldiers lies in the legislative act of July 28, 1866, which authorized the creation of six all-Black regiments: the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantry Regiments (later consolidated into the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments). For many African American men, newly emancipated from slavery, military service offered a rare pathway to stable employment, a steady income, and a measure of dignity and respect largely denied to them in civilian life. It was an opportunity to prove their worth, not just as soldiers, but as citizens of a nation still grappling with the concept of their freedom.

Recruitment for these regiments was vigorous, drawing from a diverse pool of veterans of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) who had fought in the Civil War, as well as freedmen seeking purpose and opportunity. They were commanded by white officers, as regulations at the time prohibited Black officers from leading Black troops, a stark reminder of the deeply ingrained racism within the military structure itself. Despite this inherent prejudice, the newly formed units quickly established a reputation for exceptional discipline and combat effectiveness.

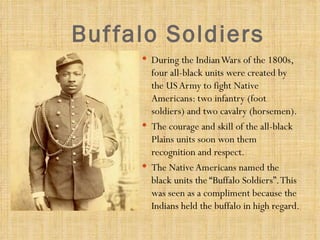

The nickname "Buffalo Soldiers" is believed to have originated with Native American tribes, most notably the Cheyenne and Comanche, who fought against them. The exact origin is debated, but the most widely accepted theory attributes it to the soldiers’ dark, curly hair, which the Native Americans thought resembled the matted, shaggy coat of a buffalo. Other accounts suggest it was a mark of respect for their fierce fighting spirit and tenacity, qualities that reminded the tribes of the buffalo’s formidable nature. Regardless of its precise etymology, the moniker was embraced by the soldiers themselves, becoming a badge of honor and a symbol of their unique identity.

Stationed primarily in the vast, unforgiving territories of the Great Plains and the Southwest – Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Kansas – the 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments faced an array of daunting challenges. Their primary duties were manifold: protecting settlers and railroad construction crews, building and maintaining telegraph lines, escorting stagecoaches and mail, apprehending cattle rustlers and outlaws, and, most prominently, engaging in skirmishes and campaigns against various Native American tribes resisting the encroachment on their ancestral lands. These tribes included the Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Sioux, among others.

Life on the frontier for these soldiers was incredibly arduous. They endured extreme weather conditions, from scorching desert heat to freezing blizzards, often with inadequate supplies and provisions. Remote outposts meant isolation from society, and the constant threat of attack, whether from Native American warriors or opportunistic bandits, demanded perpetual vigilance. Their patrols could span hundreds of miles across treacherous terrain, with minimal rest and relentless exposure to the elements.

Perhaps the most insidious challenge they faced, however, was systemic racism. Despite their uniform and their courageous service, Buffalo Soldiers were often treated as second-class citizens by the very society they protected. White civilians frequently subjected them to discrimination, harassment, and violence, refusing them service in establishments or denying them equal treatment. Within the army, they were often assigned the toughest, most undesirable posts and received older, inferior equipment compared to their white counterparts. Their white officers, though often respectful of their abilities, operated within a system that inherently limited the soldiers’ opportunities for advancement.

Yet, it was precisely in overcoming these adversities that the Buffalo Soldiers shone. Their desertion rates were remarkably low compared to white units of the era, a testament to their dedication and the value they placed on military service. Their discipline was legendary, and their combat record was exemplary. Throughout the Indian Wars, Buffalo Soldiers earned 18 Medals of Honor – the nation’s highest award for valor – a staggering achievement given the smaller size of their units and the pervasive discrimination they faced. Fourteen of these medals were awarded during the Indian Wars period.

One prominent figure whose story encapsulates both the triumph and tragedy of the era is Henry O. Flipper. In 1877, Flipper became the first African American to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point. Assigned to the 10th Cavalry, he served with distinction, demonstrating exceptional engineering and leadership skills. However, in 1881, he was unjustly court-martialed on charges of embezzlement and conduct unbecoming an officer, charges widely believed to be racially motivated. Though later cleared of embezzlement, he was dishonorably discharged. It took over a century for his name to be fully cleared, with President Bill Clinton issuing a posthumous pardon in 1999, finally acknowledging the racial injustice he endured.

The Buffalo Soldiers participated in virtually every major campaign of the Indian Wars. In Arizona, they played a critical role in the Geronimo Campaign, pursuing the elusive Apache leader through the rugged mountains. In Texas, they patrolled the vast stretches of the Llano Estacado, confronting Comanche and Kiowa bands. Their unwavering commitment to duty, often against overwhelming odds, earned them the respect of both their white officers and, in many instances, their Native American adversaries. General Benjamin Grierson, commander of the 10th Cavalry, famously stated, "I have never seen a better body of troops than the Tenth Cavalry. They are sober, industrious, and brave."

However, it is imperative to acknowledge the complex and often tragic paradox of their service. While fighting for their own dignity and equality, the Buffalo Soldiers were simultaneously instruments of a government policy that systematically dispossessed Native American tribes of their land and culture. They were, in essence, Black men fighting Indigenous men, both groups marginalized by the dominant white society. This historical irony underscores the painful complexities of American expansion and the deeply intertwined struggles of different minority groups. Their courage and service, while undeniably heroic, cannot be separated from the devastating impact of the Indian Wars on Native American populations.

By the close of the Indian Wars in the late 1890s, the Buffalo Soldiers had established an indelible record of service. Their cavalry regiments transitioned to new roles, participating in the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, and later serving in various capacities through World War II. Though their direct involvement in frontier conflicts ended, their legacy endured, inspiring future generations of African Americans to serve in the armed forces and challenge racial barriers.

Today, the story of the Buffalo Soldiers stands as a powerful testament to resilience, bravery, and the pursuit of justice in the face of systemic adversity. They were not merely soldiers; they were pioneers, nation-builders, and unsung heroes who carved out a place for themselves in American history through sheer force of will and unwavering commitment to duty. Their "red earth" – the soil they rode upon, fought over, and often died on – whispers tales of forgotten battles, quiet triumphs, and the enduring spirit of men who, despite being denied full recognition in their own time, left an indelible mark on the American West and on the broader narrative of the nation. Their echoes continue to resonate, reminding us of the diverse and often challenging paths taken to forge the America we know today.