Echoes of Resilience: The Urgent Fight for Indigenous Languages on Turtle Island

On Turtle Island, the land mass known today as North America, a profound cultural battle is being waged – one not fought with weapons, but with words. At its heart lies the urgent, often heroic, advocacy for the survival and revitalization of Indigenous languages, a tapestry of tongues that are much more than mere communication tools; they are the living vessels of history, identity, traditional knowledge, and spiritual connection for hundreds of distinct nations. This struggle is a direct response to centuries of colonial policies designed to eradicate these languages, and it represents a powerful assertion of Indigenous sovereignty and resilience.

The linguistic landscape of Turtle Island was once vibrant, home to thousands of distinct languages. Before European contact, estimates suggest over 300 Indigenous languages were spoken in what is now the United States and Canada alone. Today, a grim reality persists: UNESCO classifies the vast majority of these languages as endangered, with many critically so, possessing only a handful of fluent elders. This precipitous decline is not accidental; it is the direct, tragic legacy of state-sponsored cultural genocide.

The most devastating blow came through the residential and boarding school systems. For over a century, thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities, stripped of their cultural identities, and punished—often brutally—for speaking their ancestral languages. The explicit goal, infamously articulated by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was to "kill the Indian in him, and save the man." This systematic suppression severed the intergenerational transmission of language, creating deep wounds of trauma that reverberate to this day. Entire generations grew up without the language of their ancestors, creating a critical gap in linguistic fluency and cultural continuity.

Yet, despite this historical trauma and ongoing systemic challenges, Indigenous communities across Turtle Island are actively reclaiming their linguistic heritage with extraordinary determination. Advocacy for Indigenous languages is not a monolithic movement; it is a constellation of diverse, community-led initiatives, often driven by elders, knowledge keepers, and a burgeoning generation of youth determined to speak their truth in their own words.

One of the most vital forms of advocacy is the establishment of language immersion programs. From "language nests" for toddlers to full-scale immersion schools, these initiatives create environments where children and adults can learn and speak their ancestral languages daily. The Mohawk community of Kahnawà:ke in Quebec, for instance, has successfully implemented a comprehensive immersion program, starting in elementary schools, which has led to a significant increase in the number of young, fluent speakers of Kanien’kéha (Mohawk). This model, replicated in various forms by nations like the Navajo, Cree, Ojibwe, and Haudenosaunee, proves that with sustained effort and community commitment, languages can be brought back from the brink.

Master-apprentice programs are another cornerstone of language revitalization. These initiatives pair fluent elders with dedicated learners, often on a one-on-one basis, to facilitate intensive language acquisition through daily interaction and cultural immersion. This approach not only transmits linguistic knowledge but also fosters deep intergenerational bonds and the transfer of traditional knowledge that is often inseparable from the language itself. Imagine an elder teaching a younger community member how to harvest traditional medicines, hunt, or weave, all while speaking exclusively in their ancestral tongue – this is language learning as a holistic, cultural experience.

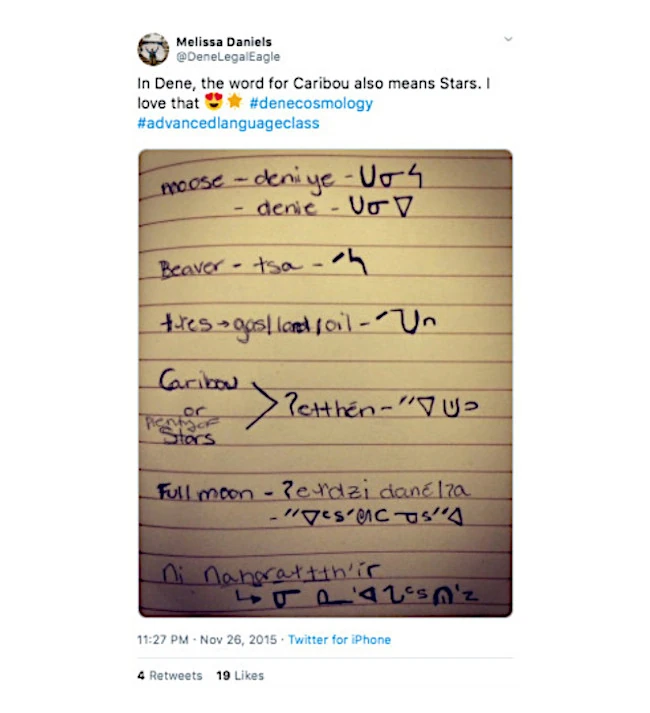

The digital age has also become a crucial battleground for language advocacy. Indigenous communities are harnessing technology to create online dictionaries, language-learning apps, social media groups, and digital archives. Platforms like First Voices, a project based in British Columbia, allow communities to record, preserve, and share their languages online, making them accessible to learners worldwide. Podcasts, YouTube channels, and even video games are being developed in Indigenous languages, engaging younger generations on their own terms and demonstrating the adaptability and modernity of these ancient tongues. The internet allows for unprecedented reach, breaking down geographical barriers and connecting learners with resources and other speakers.

Beyond community efforts, policy and legislative advocacy play a critical role. In Canada, the Indigenous Languages Act (2019) was a landmark piece of legislation, committing the federal government to supporting the revitalization and maintenance of Indigenous languages. While its implementation and funding remain subjects of ongoing debate and advocacy, it represents a significant step towards recognizing linguistic rights. Similarly, in the United States, the Native American Languages Act of 1990 and its subsequent amendments have provided some federal support, albeit often insufficient, for tribal language programs. Advocates continuously push for increased, stable, and culturally appropriate funding, arguing that language revitalization is not a luxury but a fundamental human right and a crucial component of reconciliation.

The connection between language and land-based learning is also a powerful aspect of advocacy. Many Indigenous languages are deeply intertwined with the specific ecosystems, landscapes, and traditional practices of their respective territories. Learning a language while on the land—identifying plants, animals, and geographical features with their Indigenous names, engaging in traditional harvesting or ceremonies—reinforces both linguistic and cultural knowledge in a profoundly holistic way. This approach re-establishes the vital connection between language, land, and identity, recognizing that the language itself often holds the instructions for living in balance with the environment.

The challenges, however, remain formidable. The sheer number of fluent elders continues to dwindle, making the urgency of intergenerational transfer paramount. Funding, while improving, is often inconsistent and inadequate to address the vast needs of hundreds of languages. The lingering effects of intergenerational trauma can impact language acquisition and cultural engagement. Furthermore, the dominance of English and French in education, media, and economic life creates a constant pressure against the use of Indigenous languages.

Despite these hurdles, the spirit of perseverance is undeniable. The advocacy for Indigenous languages is intrinsically linked to broader movements for self-determination, decolonization, and cultural resurgence. When a language is revitalized, it doesn’t just benefit the speakers; it strengthens the entire community. It enhances mental and spiritual well-being, fosters a stronger sense of identity, and unlocks traditional knowledge essential for addressing contemporary challenges, from environmental stewardship to mental health.

As Dr. Marie Battiste, a Mi’kmaw scholar, eloquently states, "Language is the heart of Indigenous identity." It is the lens through which worldviews are understood, stories are told, and ceremonies are performed. The fight to keep these languages alive is not merely about preserving words; it is about preserving entire ways of knowing and being. From the quiet determination of elders sharing stories in their mother tongue to the vibrant online communities of youth exchanging phrases, the advocacy for Indigenous languages on Turtle Island is a powerful testament to resilience, a beacon of hope for cultural continuity, and a fundamental act of reclaiming what was stolen. It is a long, arduous journey, but one undertaken with an unwavering commitment to ensure that the echoes of ancestral voices continue to resonate across the land for generations to come.